By Chandler Countryman / NORTHWEST PACIFIC OCEAN /

Chandler Countryman is a graduate student at the University of Georgia, studying the vertical transport of organic matter from the surface to the deep ocean.

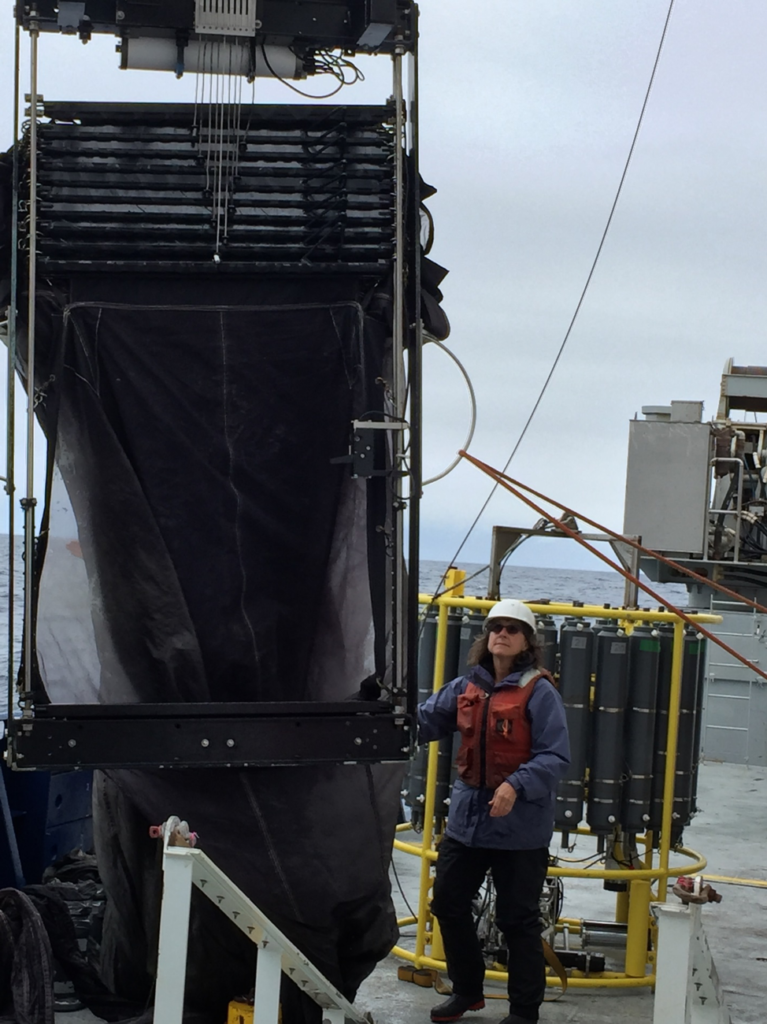

The Multiple Opening/Closing Net and Environmental Sensing System, or MOCNESS, is used to look at zooplankton, sea creatures ranging in size from microscopic to several inches. We’re interested in learning what types are present in the water column, how many there are, and at what depth they are found. As you go down in the water column the community of planktonic animals change, and the depth at which each type of zooplankton is found can change throughout the day, depending on the species. This is referred to as “diel vertical migration” and allows animals to swim to shallower depths during the night to feed and then retreat to deeper depths during the day in order to avoid being eaten by visual predators.

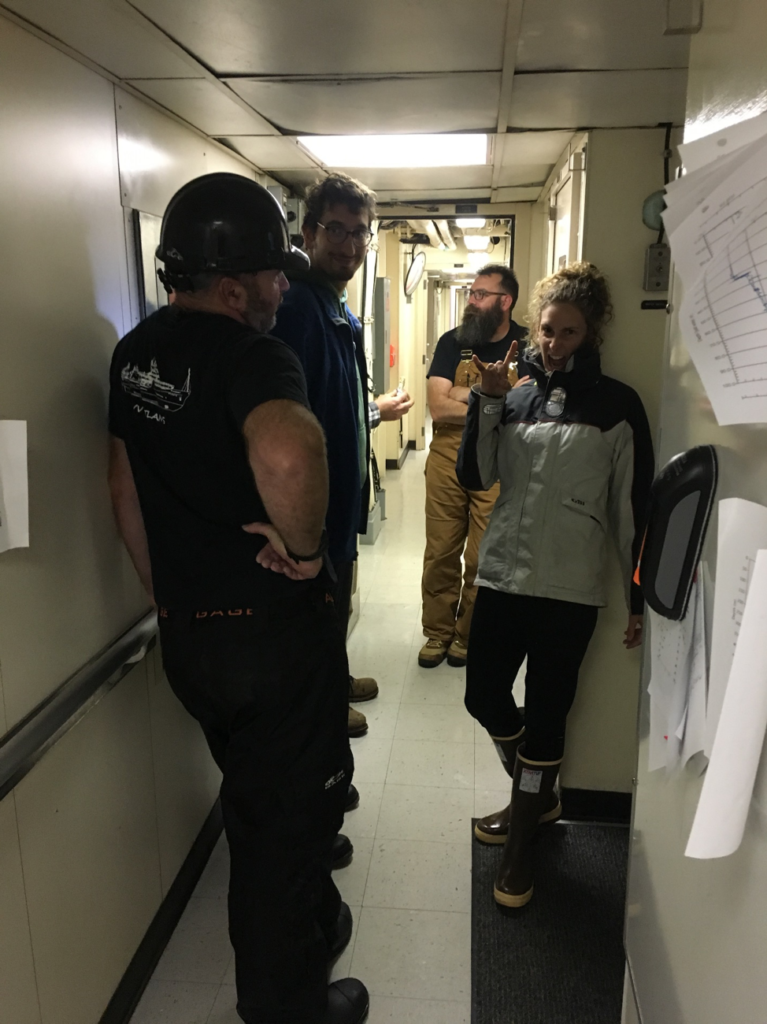

The MOCNESS is a one-meter square frame with ten individual nets and each one can be opened at different desirable depths. The zooplankton team aboard the R/V Roger Revelle, led by Dr. Debbie Steinberg of the College of William & Mary, has sent the MOCNESS down to 1000 meters ten times so far during the EXPORTS cruise, five times during the day and five times during the night. The day/night pairs allow us to look at this diel vertical migration behavior.

In addition to our beloved epipelagic (surface) and mesopelagic (intermediate depth) zooplankton species, we have also caught several neat, deep-sea animals.

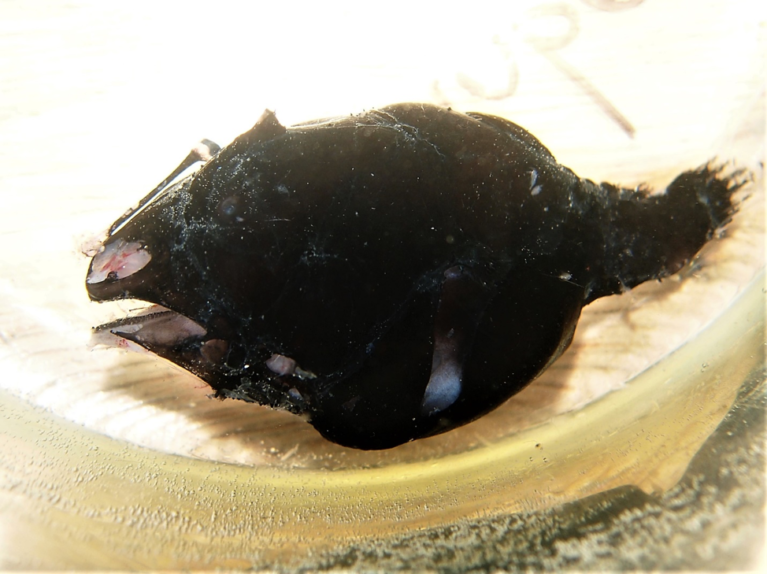

The Anglerfish

Common name: Spikehead dreamer, Scientific name: Bertella idiomorpha

This beautiful fish was caught in our net that stays open from 0-1000 meters, so the exact depth in which it was caught is unknown. In general, this species of anglerfish can be found anywhere between 805 meters and 3475 meters deep.

Most anglerfish are quite small and the maximum length recorded for this species is 10.2 cm (SL). It is dark-grey in color with a large head that has sharp teeth in its wide mouth. The most characteristic feature of this fish—and the reason for its name—is its lure (esca), which glows with the help of bioluminescent bacteria.

The lure attracts small animals like crustaceans and fish and is only found on females. The males are much smaller than the females and start out as free-swimmers until encountering a female, at which point they dig their teeth into the female, and inject enzymes that break down skin, fusing themselves into the female. Once the male is fused with the female, its bloodstream is actually connected to hers, and then the males loses all organs except for his testes.

This form of symbiosis is considered an adaptation to the low encounter rate experienced between individuals in the deep sea. The male gets nutrition from the female, and in return the female has available sperm for multiple spawning events.

The female that we caught was still alive when she was brought on deck and we were able to film her swimming for a bit and to see the glow of her lure by going into a dark room—which in this case was the bathroom.

The Viperfish

Common name: Pacific viperfish, Scientific name: Chauliodus macouni

This gnarly-looking predatory fish is a vertical migrator that lives between 200 and 5000 meters deep during the day and swims up to less than 200 meters at night to feed. This species can reach a length of about 30 centimeters (1 foot) and is black/dark brown in color with photophores along its side, which are thought to be used as camouflage from predation below them in the water by making them blend in with the light from above. It is also possible that these photophores can attract prey or be used in mating.

The most striking feature of the viperfish is its teeth, which are so large that they can’t fit inside its mouth and instead curve up towards the eye. Instead of being used for chewing, these teeth are used to impale its prey by swimming into it at fast speeds. The viperfish mostly eats crustaceans, arrow worms, and small fish. It has several adaptations to survive a low prey encounter rate in the deep ocean, including a hinged skull that allows it to swallow large prey, a large stomach that allows it to stock up on prey while it is abundant, and a low metabolic rate, which allows it to go several days without food.

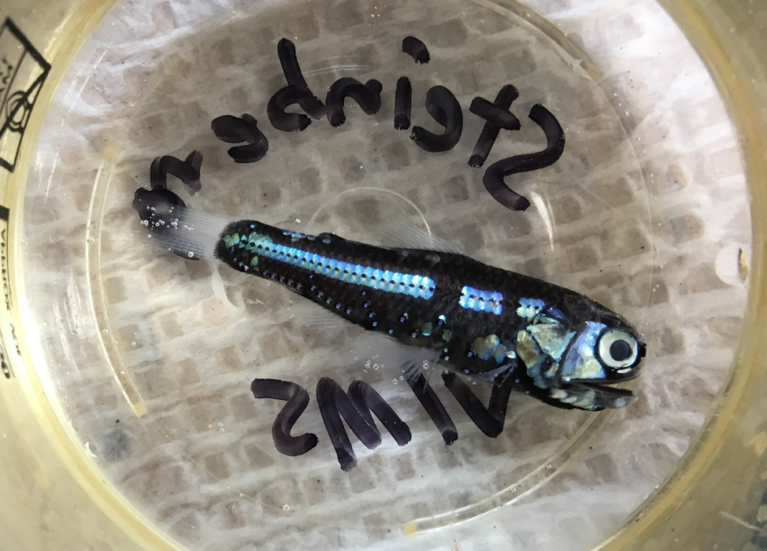

The Lanternfish

Common name: Lanternfish, Scientific name: Family Myctophidae

Myctophids are very common in the world’s oceans and can make up to 65 percent of the fish biomass in the deep sea. Most lanternfish are smaller than 15 centimeters (5.9 inches) and are diel vertical migrators that live between 300 and 1500 meters during the day and swim up to between 10 and 100 meters during the night to avoid predators and also to follow their food source, which consists mostly of vertically migrating zooplankton. These fish also possess photophores along their body, which can be used for camouflage just like the ones found on the viperfish. However, the photophores in lanternfish differ greatly between species, which indicates that it may also be used for communication and mating.

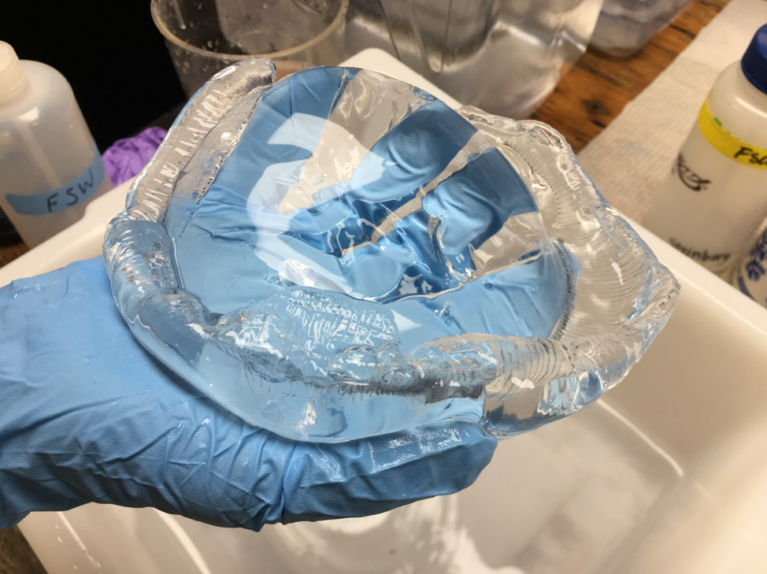

The Helmet Jelly

Common name: Helmet jellyfish, Scientific name: Periphylla periphylla

This deep-sea jelly is a vertical migrator that can be found between 500 and 1000 meters and avoids too much light because its red-brown pigment becomes lethal with light exposure. The umbrella can be up to 35 centimeters (~14 inches) in height and 25 centimeters (~10 inches) in diameter and is completely clear, showing the red/orange stomach inside of it. It has 12 orange tentacles that can be more than 50 centimeters (~20 inches) long, which have stinging cells on them to attack their prey. This jellyfish can actually use bioluminescence to produce flashes of bright light in order to protect itself from predation by confusing its predators. A helmet jelly’s body is 90 percent water.

Other neat critters

We have caught many more creatures including deep-sea shrimp, other jellies, squid, ctenophores and many more!