My name is Mandy Bayha and I am from a small community called Délįnę [pronounced De-lee-nay] in Canada’s Northwest Territories. With a population of about 500, the community is nestled on the shores of the southwest Keith arm of the beautiful Great Bear Lake. The Sahtúotįnę (which means “people of Great Bear Lake”) have been its only inhabitants since time immemorial. The community is rich in culture and language and has a deep sense of love and connection to the land, especially the lake. I am a student in environmental science and conservation biology and also the indigenous healing coordinator (an initiative called “Sahtúotįnę Nats’eju”) for the Délįnę Got’įnę government. Under the guidance and mentorship of the elders, knowledge holders, and leadership of my community, I have been tasked to facilitate and implement a pilot project that aims to bridge the gap between traditional knowledge and western knowledge to create a seamless and holistic approach to health and wellness.

Traditional knowledge is relevant to everything we do, from healing, governance, and environmental management to early childhood development and education. Traditional knowledge encompasses virtually every human relationship and dynamic and outlines our relationships with each another, our Mother Earth, and our creator. As our elders say, “We are the land and the land is us. The land provides everything to us and is like a mother to us all and we all come from her.” It is our belief that everything is interconnected and in a constant relationship, forever and always.

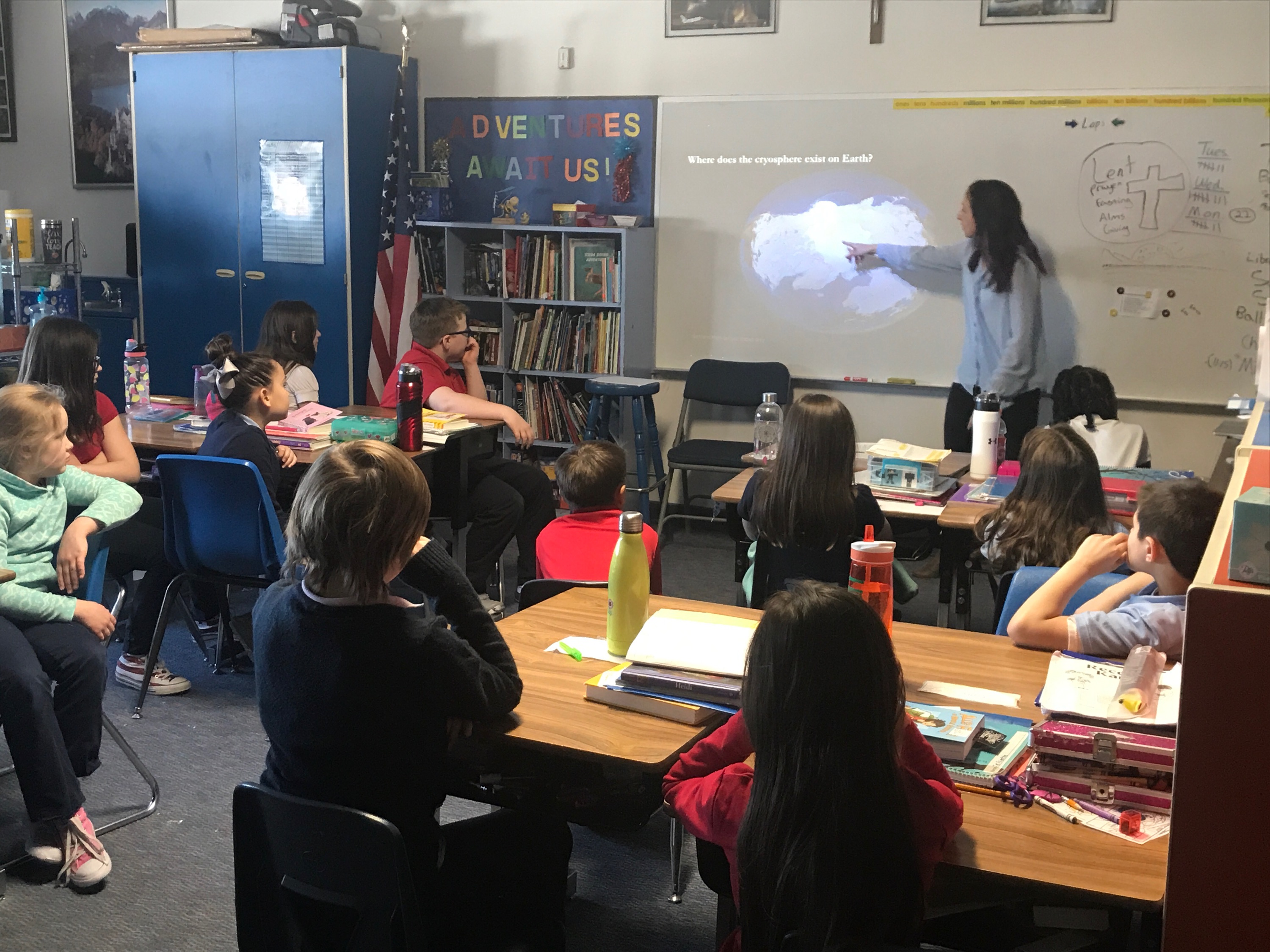

On August 20 I traveled to Yellowknife to participate in the Arctic-Boreal Vulnerability Experiment, or ABoVE. Currently in its second year, this 10-year project is focused on the vulnerability and resilience of the Arctic and on understanding the effects of climate change on such a delicate ecosystem. ABoVE is important because it can provide a holistic view of climate change in the north by bringing together two knowledge systems: the traditional knowledge of my ancestors and western science. In fact, the project’s first guiding principle is to “recognize the value of traditional knowledge as a systematic way of thinking which will enhance and illuminate our understanding of the Arctic environment and promote a more complete knowledge base.”

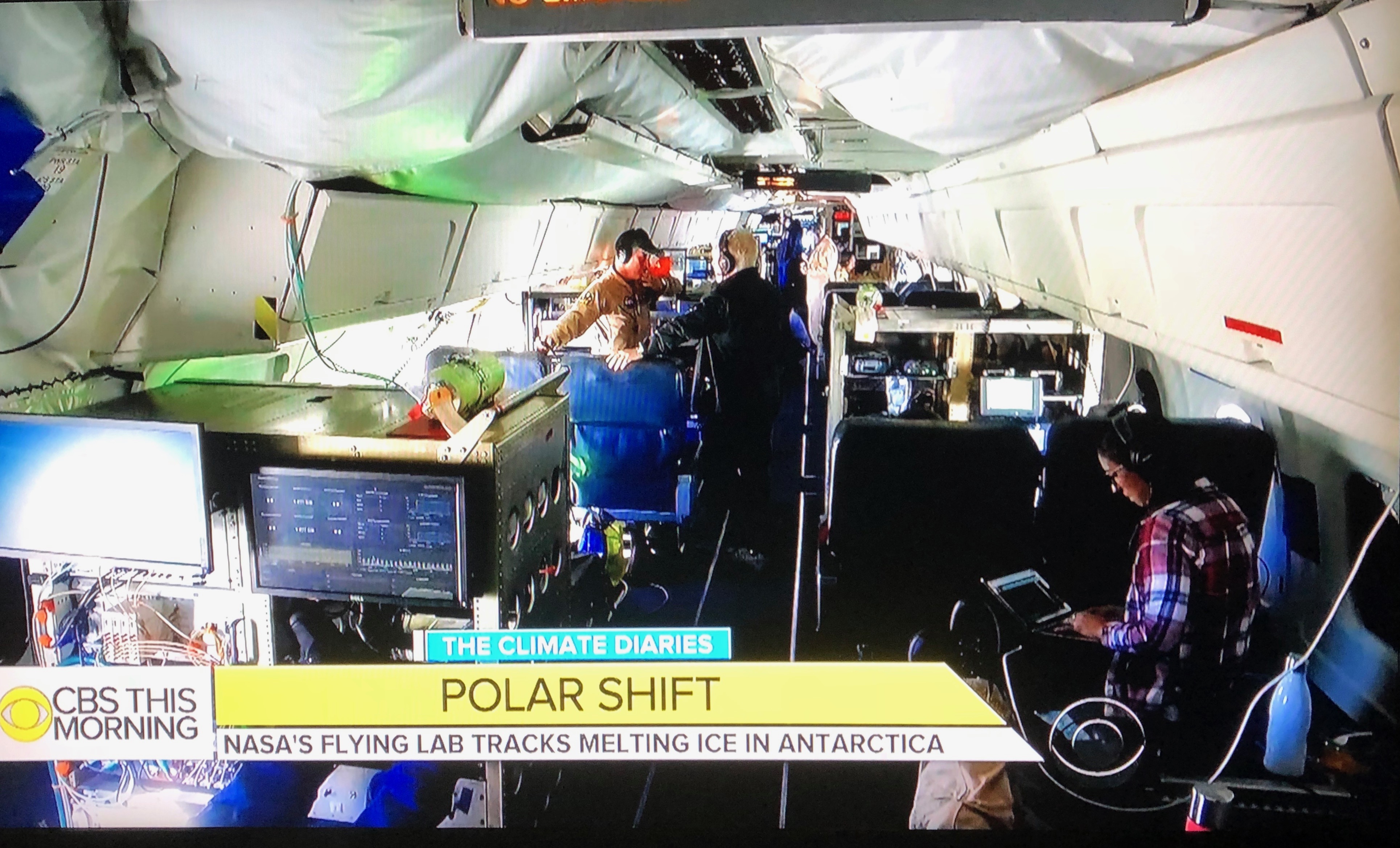

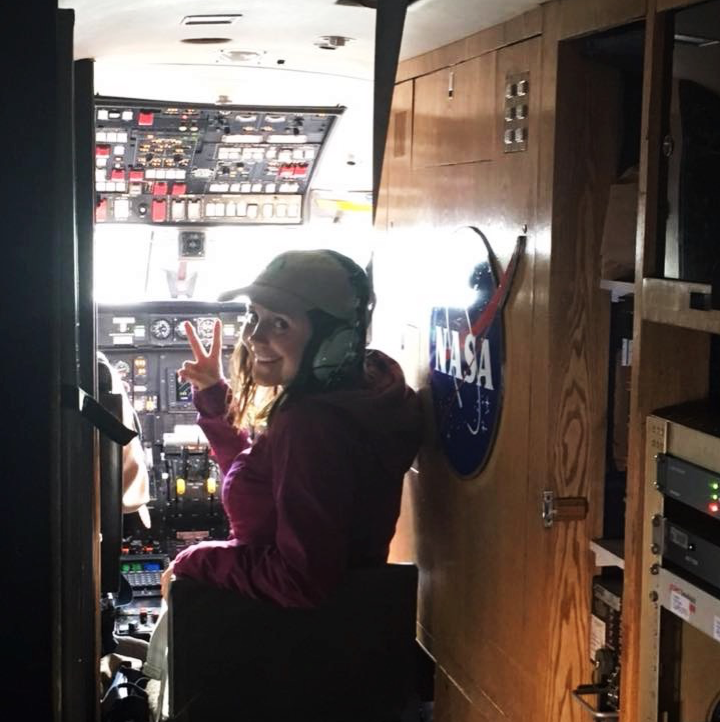

I was able to participate in this incredible opportunity with a fellow Délįnę woman named Joanne Speakman, who is also an environmental science student. Our first day started on August 22, bright and early at 8 o’clock in the morning. We met the flight team at the Adlair Aviation hanger to undergo a safety briefing and egress training. It was like walking into a scene from the movie Armageddon. The two ex-U.S. Air Force test pilots were speaking a technical language riddled in codes, and the remote sensing engineers were spouting their checks and balances. I was thrilled to be surrounded by NASA employees all adorned in patches, jumpsuits, and ball caps. Afterward, Dr. Peter Griffith, the project lead, explained everything to Joanne and me in plain language. We then took a tour of the plane and learned how to exit in the unlikely event of an emergency. We were treated so nicely, and I felt more than welcome to participate.

We were invited to sit in a jump seat situated right behind the pilots during take-off and landing. Joanne got take-off and I got landing. What an experience that was! During our four-hour flight, which took us from Yellowknife to Scotty Creek (a permafrost research site near Fort Simpson), Kakisa, Fort Providence, and back to Yellowknife, Dr. Griffith sat with us and explained the ABoVE project. He gave us background on how the “lines”—the strips of areas that were scanned by the radar—were chosen and filled us in on research done in those areas previously, such as major burn sites, permafrost melt, carbon cycling, and methane levels. He referred to pictures while explaining how certain equipment as well as ground data calibration and validation techniques were used.

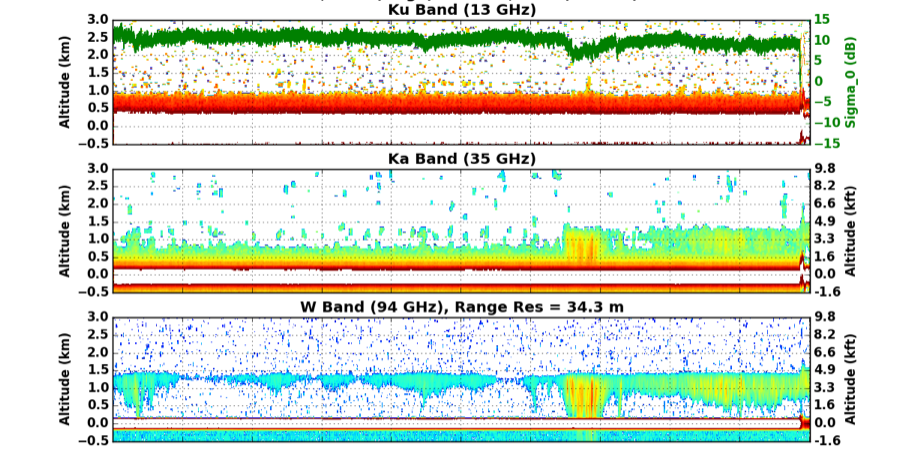

We also chatted with engineers from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, who manned the remote sensing station on the flight. They explained that the remote sensing equipment, which was welded to the bottom of the Gulfstream III jet, is made of many tiny sensors that send signals to the ground that bounce back to a receiving antenna on the aircraft. The resulting data tell a story of what is happening on Earth’s surface, revealing features such as inundation (marshy areas where vegetation is saturated with water) and the rocky topography from the great Canadian shield, for example. The sensor they’re using is called an L-band synthetic aperture radar (SAR), which has a long wavelength ideal for penetrating the active layer in the soil. This is important for many reasons but mainly for indicating soil moisture.

When flying above target areas, the pilots had to position the plane precisely on the designated lines to trigger the L-band SAR on the bottom of the plane, which would put the aircraft on autopilot mode and allow the sensor to “fly” the plane for the entire length of scanning the line. Once the scan was complete, the pilots would then take control of the plane again. The precision and accuracy for all those things to work in tandem was extraordinary to witness.

After the last scan, I hopped into the jump seat directly behind the pilots and watched them land the plane. Once on the ground, we were greeted by reporters with Cabin Radio (a local NWT radio station) who interviewed us and took our pictures with the Gulfstream III jet in the background. It was an absolute honor and a once-in-a-lifetime experience that I will never forget.

Fortunately, our incredible journey with NASA wasn’t yet complete. Joanne and I tagged along with two scientists, Paul Siqueira and Bruce Chapman, who are helping to build an Earth-orbiting satellite called the NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar, or NISAR. We met up with Paul and Bruce early on the morning of August 24 and identified two lakes located just off the Ingraham Trail, a few kilometers outside of Yellowknife, to collect data that will help in the creation of algorithms to capture and interpret wetland and inundated sites via satellite and remote sensing. We reached the shores of the first lake and split into two groups, one scientist and one student per group. We walked in separate directions in areas of inundation between the open water and the treeline surrounding the lake and took measurements using an infrared laser for accurate distances between the treeline and open water and made estimations and diagrams to fully detail the ground view.

We tackled the second lake with a canoe and could not have asked for better weather. We enjoyed our afternoon bathed in the sun. The waterfowl and minnows shared their home with us for a time. During our canoe ride, we learned a lot more about our scientist friends. They were part of a launch that carried some of the first remote sensing technology into space. This technology was then used to study the surface of Venus and Mars. How fortunate were Joanne and I to be able to listen and learn from such a brilliant crew of scientists who have had amazing careers.

It was an enriching and humbling experience to participate in the ABoVE project. If an organization such as NASA realizes that indigenous traditional knowledge is both valid and important, then I am hopeful for our next generation of indigenous people. I believe that this is the first step in reconciliation: acknowledgment and appreciation. I would be honoured to participate again; however, I am more than grateful to know that there is this collaboration happening and that it includes the indigenous Dene of the north.

Mahsi Cho (thank you)!