by Roberto Molar Candanosa

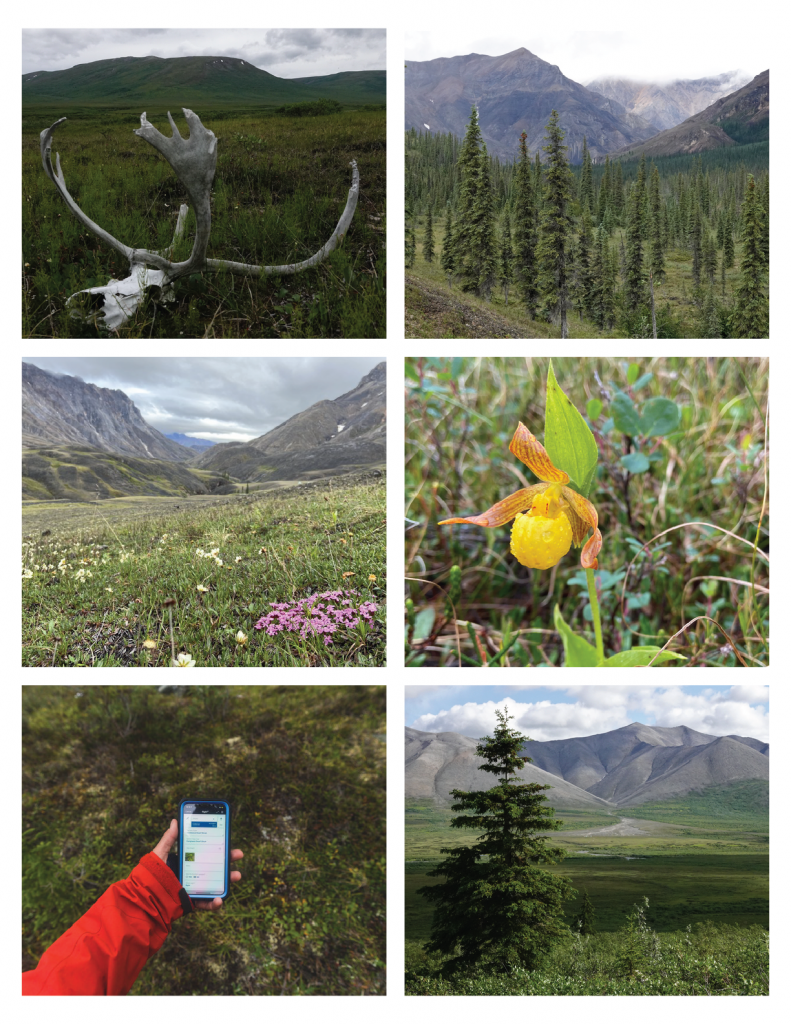

Far up in northern Alaska, Logan Berner’s legs are burning with pain from trekking over tussocks in grassy valley bottoms and rugged, cloud-choked mountain passes. He’s spending a couple of weeks of 2021’s summer traversing the mountainous Brook Range, carrying just the essentials to sustain him in the expanse of the Alaskan Arctic. There, where North America ends, tundra and mountains make up one of the continent’s most pristine landscapes.

The Brooks Range is not the sort of environment where people just go for a hike. It’s too remote, too wild, and too cold. There are no human trails other than what’s left behind by moose, bears and other wild animals roaming the region. It’s the kind of terrain that will get you in trouble, the kind that would put you face to face with a hungry grizzly bear or give you hypothermia.

Rain gear is non-negotiable. 2021 marked one of the wettest summers on record in the range, and some days in the trek feel like an endless walk through a car wash. Stopping for more than a few minutes (even to eat) will make your body too cold from the whipping wind and pouring rain near freezing temperatures.

Berner, a research ecologist from Northern Arizona University, went out there to join a group of biologists led by Roman Dial, a professor of biology and mathematics at Alaska Pacific University who had been traversing the range on foot for nearly a month. Covering nearly 800 miles in about three months, the team used their smartphones to take pictures and jot down extensive notes about the vegetation they passed, noting when and how the type and density of trees, shrubs and other plants changed along their way.

By combining those notes with techniques that analyze greenness from space, the team wants to gain a better understanding on the extent and nature of the impacts of climate change right at the boundary between Arctic tundra and boreal forest. The idea is to use that data, recorded the old-fashioned way with boots on the ground, and link them with NASA’s long-term satellite observations.

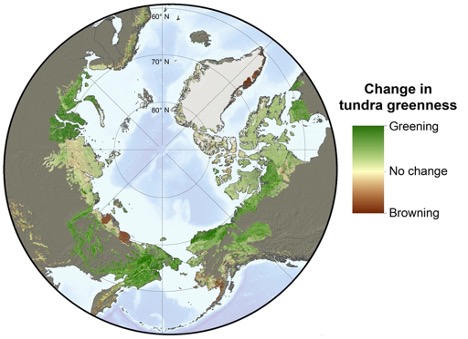

The Arctic is warming nearly twice as fast as other regions on Earth, and the impacts extend beyond glaciers melting, sea ice shrinking and other types of vanishing polar ice. They reach most deeply into places such as the Brooks Range, where Arctic tundra—a harsh, treeless ecosystem where mostly small plants grow—has become increasingly greener.

Over the last four decades, satellites have detected that greening, as well as some browning, where extreme weather, insect pests, and other disturbances reverse the greening trend. But even though satellite records suggest Arctic tundra ecosystems are changing in response to atmospheric warming, important details remain unclear about why specific regions have greened or browned in recent decades.

“Arctic greening is really a bellwether of global climatic change,” Berner said. “We know that this greening signal in part reflects warmer summers, increasing the amount of plant growth that’s occurring on the landscapes, so that the satellites are seeing this increase in leaf area.”

Already, the effects of these vegetation changes point towards other impacts as the Arctic tundra becomes more productive and shrubbier.

For example, Berner explained, thriving shrubs could out compete smaller plants that serve as important subsistence resources, like blueberries, which help sustain northern human communities. Dial also has observed that these vegetation changes can re-shape the landscape and affect how caribou and other migratory animals navigate the Brooks Range, also affecting the availability of subsistence resources for isolated villages depending on wildlife.

On the flip side, new spruce tree forests can also help insulate the thawing permafrost and possibly reduce the release of deep pools of carbon stored within it, adding more heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere.

“In that sense, [greening] might slow the rate of climate change by keeping that organic-rich permafrost carbon soils frozen and locked away,” Berner said.

Because of the unknowns revolving around Arctic greening and browning, field data serves as a crucial complement to satellite observations. Gradients of vegetation stripe the Brooks Range, making it an ideal location to sample from, as the mountains form a natural barrier that separates the boreal forest of Alaska’s interior from the Arctic tundra of Alaska’s North Slope.

NASA’s satellites can track large-scale vegetation changes from space. But 700 miles up in space, they mostly get a top-down view of the terrain. By venturing into the wilderness to collect the extensive ecological field data that is impossible to capture from space, Berner and Dial’s team are helping the satellites “see” more and better.

The team is combining their detailed notes from the ground with satellite observations of the region by the Landsat program. Ultimately, linking both datasets can help scientists learn more details about where, why, and how large patches of the Arctic’s flora are changing.

“Being on the ground and walking through these landscapes gives you a much better sense for what these landscapes are,” Berner said. “It gives you an understanding of these ecosystems that you just can’t get by sitting at a computer and crunching data.”

The team was able to trek and take data largely thanks to Dial, who has travelled over 5,000 miles throughout the Brooks Range during the last four decades. As part of that exploration, Dial developed ingenious ways to travel light for extended periods of times, making it more manageable to collect data from the field.

“When doing fieldwork in remote Arctic, Antarctic and alpine environments, survival comes first, so you can sometimes feel lucky to perform any research along the way at all,” Dial said. “But our methods of travel have evolved to the point where we can travel light and comfortably—dealing with rivers and bears and rain and wind. By integrating that light and comfortable mode of travel with smartphones and simple tools like tape measures and tree increment borers, as well as other apps on our phones that can measure heights, we can actually collect valuable and useful data across vast swaths of wilderness.”

What really makes recording data on the field possible is what Dial named “pixel walking,” a unique way in which a group of trekking scientists document observations about the vegetation as they see it on the ground, logging changes in plant types, attributes, and location continuously. Their protocols to record that information cover 30-square-meter plots of land, or a pixel of a view from a Landsat satellite.

Most previous field research has involved establishing field plots and meticulously characterizing the plant community in each one. That does provide valuable information, but the approach is expensive, limited in extent and time-consuming. Because field plots tend to be small and few, it can be difficult and prohibitively expensive to cover large areas accurately, and to match them with observations from space.

With a smartphone app developed by Dial’s team, the trekkers note the tallest plant community and its physical structure as might be seen from an orbiting satellite. They also record what isn’t so easy to see from space: the understory and ground cover. As they walk, they record on their smartphones’ app the identity and density of each of three layers of vegetation. The app also records the geographic location with the phone’s GPS.

“It’d be very expensive to collect this kind of data with a helicopter,” Dial said. “This is a really important aspect of ground truthing and calibrating what the satellites see with what’s on the ground. From satellites we only know that the reflectance values are changing over time, but we don’t know what it is that’s changing on the ground. So this is a way to find out what is really happening with plant communities and the Earth’s surface and relate it to the last 20 years of satellite data.”

Berner, supported by NASA’s Arctic Boreal Vulnerability Experiment (ABoVE for short) and Dial’s team, supported by NASA’s Alaska Space Grant, the National Science Foundation’s Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research, and the Explorers Club/Discovery, are already working to link their field observations with satellite data. What they’ll learn can also help inform future research in other parts of the Arctic.

“What is the greening that we see? Is the greening an increase in willows, for example? Is it an increase in birch? Or is it an increase in alders? Or is it an increase in trees?” Dial said. “Having a small team like mine actually on the ground to provide the ABoVE program with ground-based data—that’s really what ABoVE is doing well. It’s just a really wonderful marriage between field data collection and remote sensing.“