by Kate Ramsayer / BARROW, ALASKA /

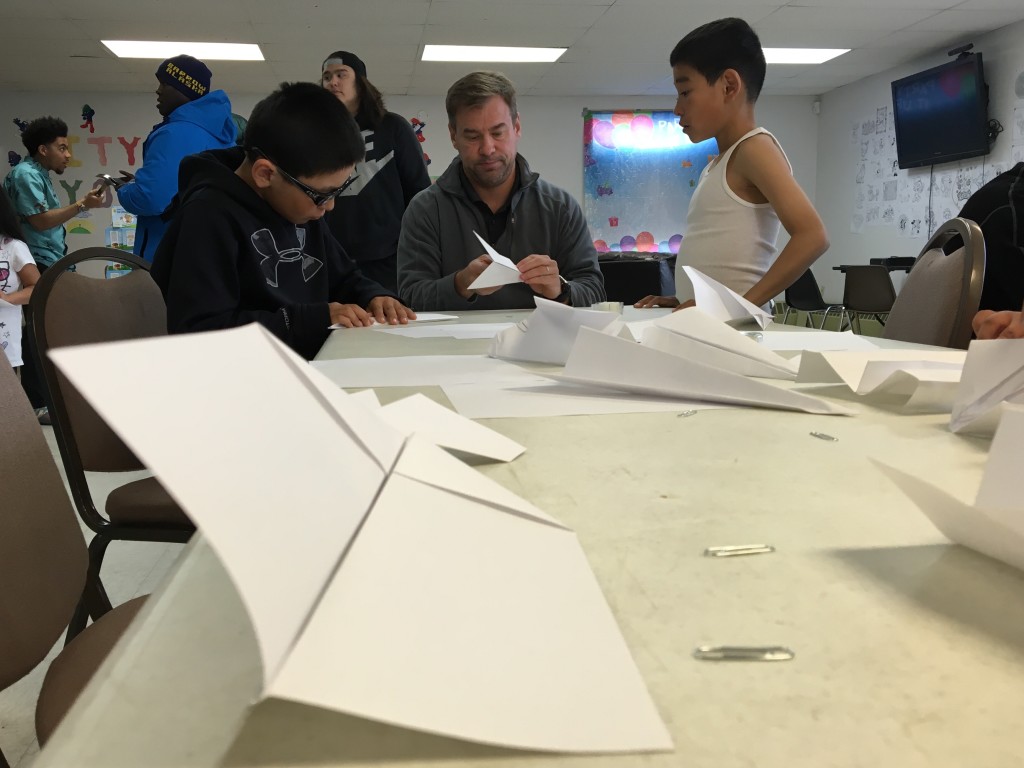

A cloudy day in the middle of Operation IceBridge’s summer campaign in Barrow, Alaska, meant no flights that day, so instead several members of the campaign showed local kids how to build and fly NASA-quality paper airplanes.

“This is what an engineer does, see what works and what doesn’t,” pilot Rick Yasky told one elementary-age summer camper.

The campaign, which measured melting sea ice in the Arctic, was the first IceBridge mission out of Barrow, so while in town the 11 scientists, pilots and flight crew explored the local science, culture and community.

One of the flight crew was walking along the beach when he came across fishermen pulling in a line of salmon—he helped, and walked back to the hotel with enough fish to eat for the rest of the campaign. Another chatted with local women who were removing reindeer tendons, which would dry out until the fall when the women would braid them together to use in sewing.

And in the middle of the campaign, they helped at a summer camp by making birdhouses, holding a paper airplane contest and showing the campers the NASA Falcon jet out of Langley Research Center in Virginia.

“When anyone comes up, we like to have them visit with the kids,” said Chris Battle, Barrow recreation director and deputy mayor. “We’re isolated so it’s good to let them have exposure to these things.”

John Woods, IceBridge project manager, also gave a library talk on how NASA measures sea ice and Arctic health, speaking to whaling captains, scientists, locals and three kids in astronaut suits. Woods and others also talked with local researchers working on the tundra with carbon monitoring stations, weather instruments and more.

This is the first time that IceBridge has been based in Barrow—the farthest north town in the United States. And the mission hopes to use it as a base to fly out again, Woods said.

“It’s an ideal location, between the Beaufort and Chukchi seas,” he said, referring to two of IceBridge’s research destinations. “We couldn’t have gotten better support from the City of Barrow and the local community. They’ve been terrific, and we’d love to see our relationship with them grow.”