By Erica McNamee, Science Writer at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center //OVER NEW YORK STATE//

I grew up flying in planes. I’m comfortable in them. But there’s one part of flying I’ve never gotten used to: turbulence. It’s common on commercial flights, so over the years I’ve learned a few tips and tricks on how to stay calm when my mind seems to take off at a sprint.

First, keep an eye on the professionals. On commercial flights, if the flight attendants are up and moving, I relax.

Second, look out the window! It not only helps to see what you’re headed into, but the views? Spectacular.

Finally, breathe deep and ignore the bumps.

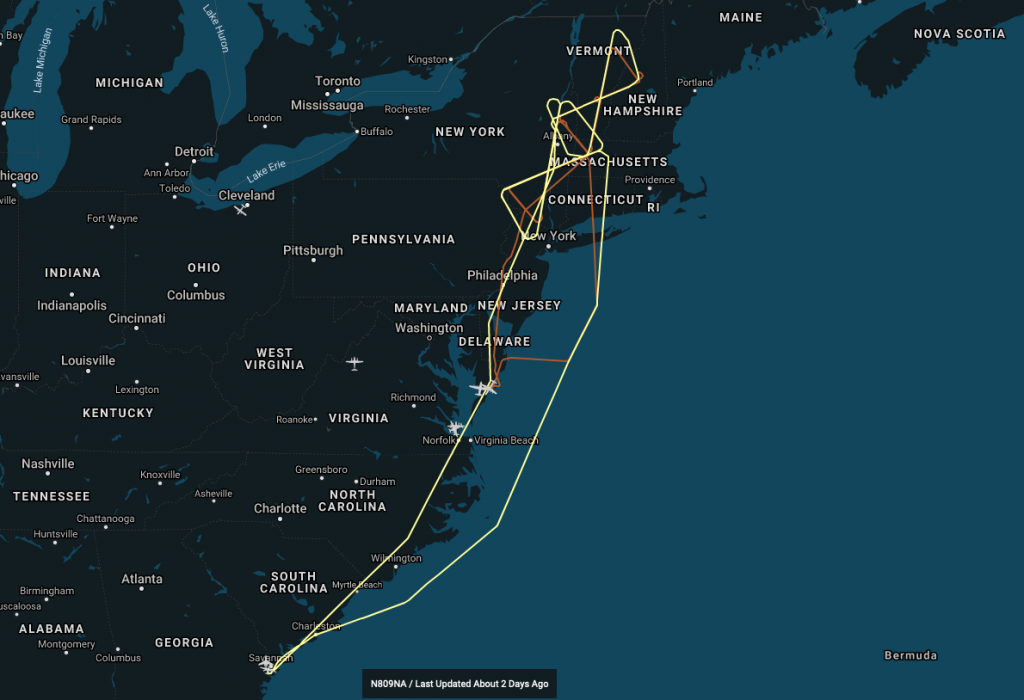

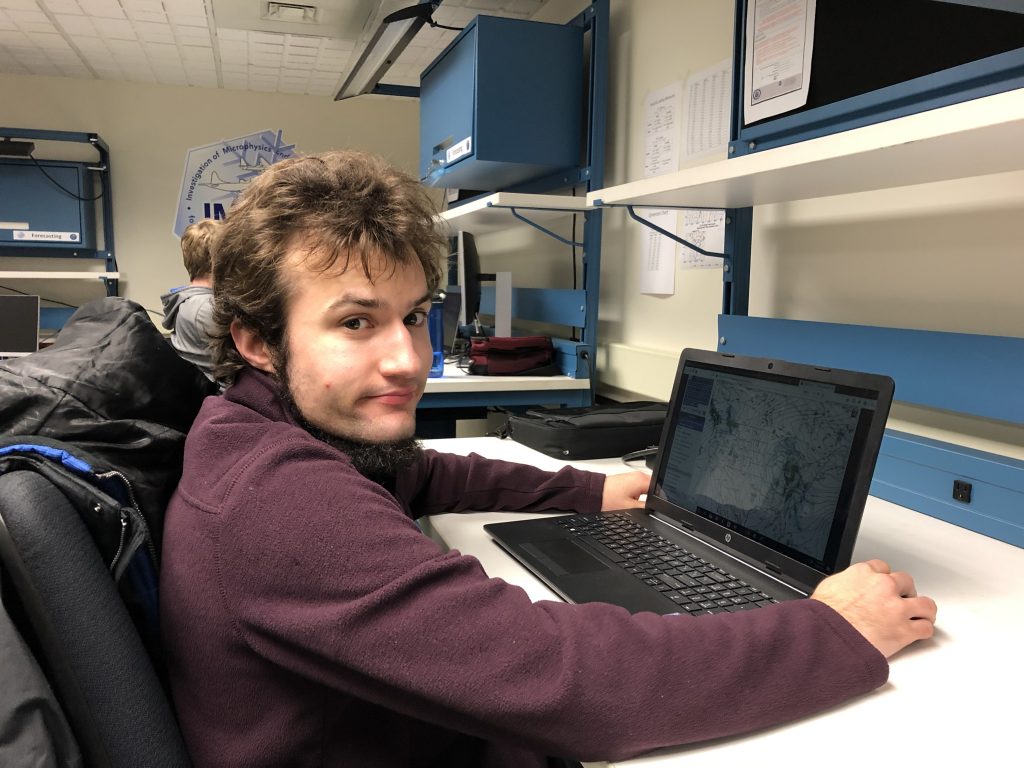

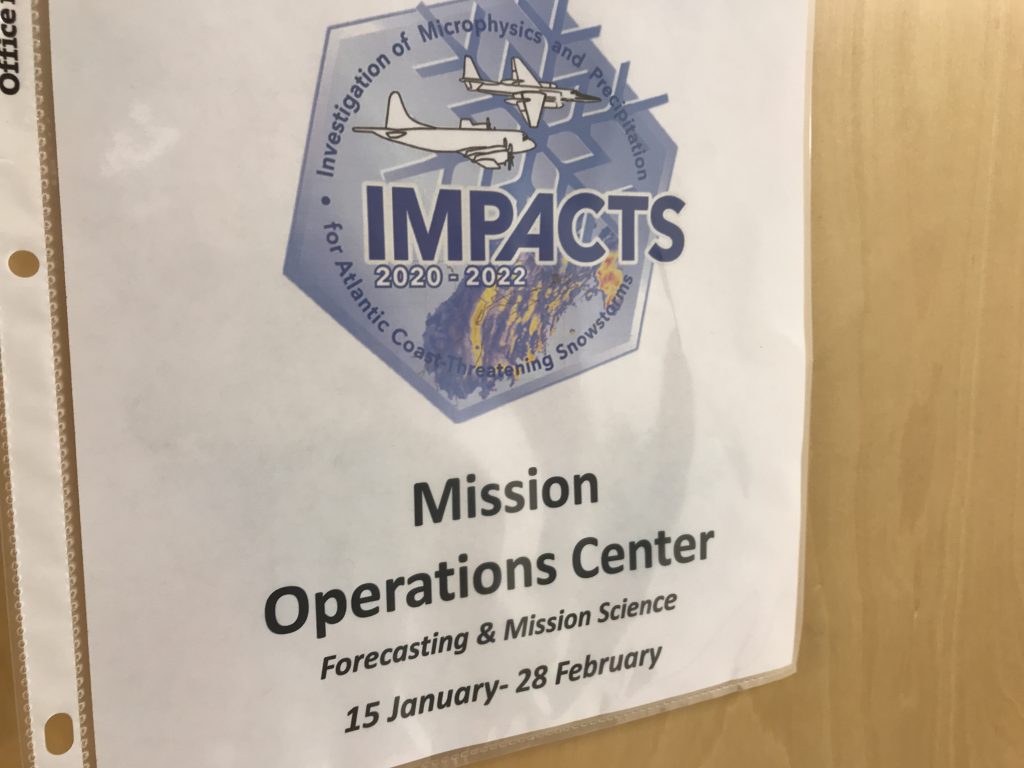

But a recent flight, my tried and true tricks didn’t work. This blog comes to you from NASA’s P-3 plane for the Investigation of Microphysics and Precipitation for Atlantic Coast Threatening Snowstorms (IMPACTS) field campaign.

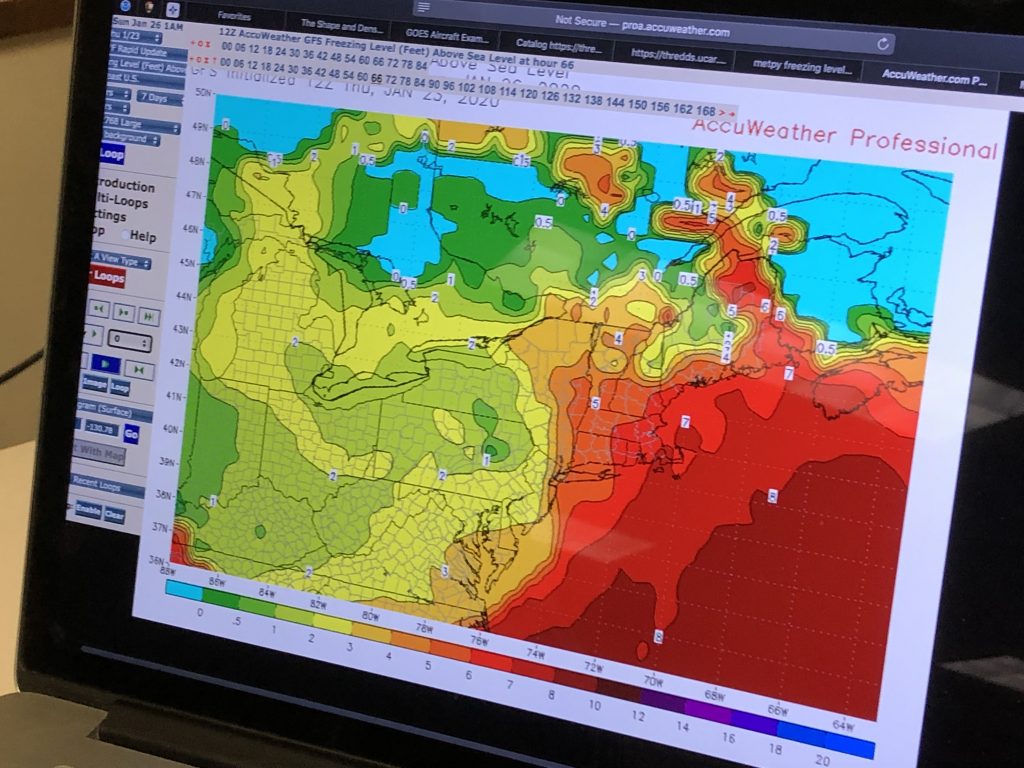

We’re flying through snowstorm clouds… seeking out turbulence … for 8 hours … on purpose. The scientists onboard want to find out how clouds form to ultimately improve the prediction of winter weather.

The scientists were focused on the data they were gathering, and not often walking around, so it wasn’t as easy to gauge the severity of the turbulence by them. Unfortunately, there were also very few windows, and even looking outside of them didn’t prove helpful, because I could almost always only see into the gray clouds we were flying through. And finally, it was verydifficult to ignore the bumps as we chased down the storm clouds.

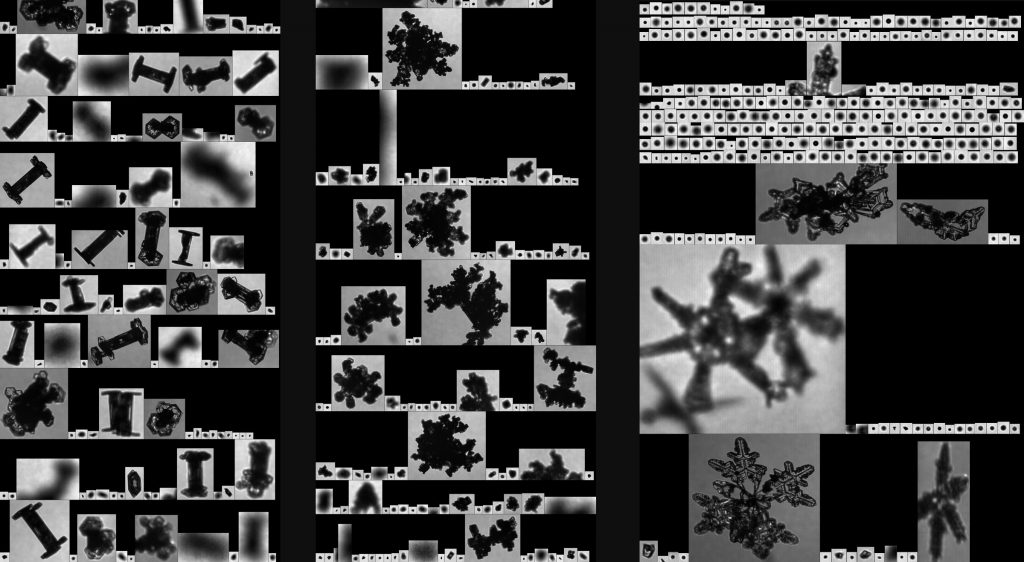

“It is important to get measurements of cloud properties directly,” said Greg McFarquhar, director of the Cooperative Institute of Severe and High Impact Weather Research and Operations (CIWRO) and professor at the school of meteorology at the the University of Oklahoma. “The detailed measurements of size distributions, high resolution particle imagery, humidity, total water content, and vertical velocities are not available by any other means.”

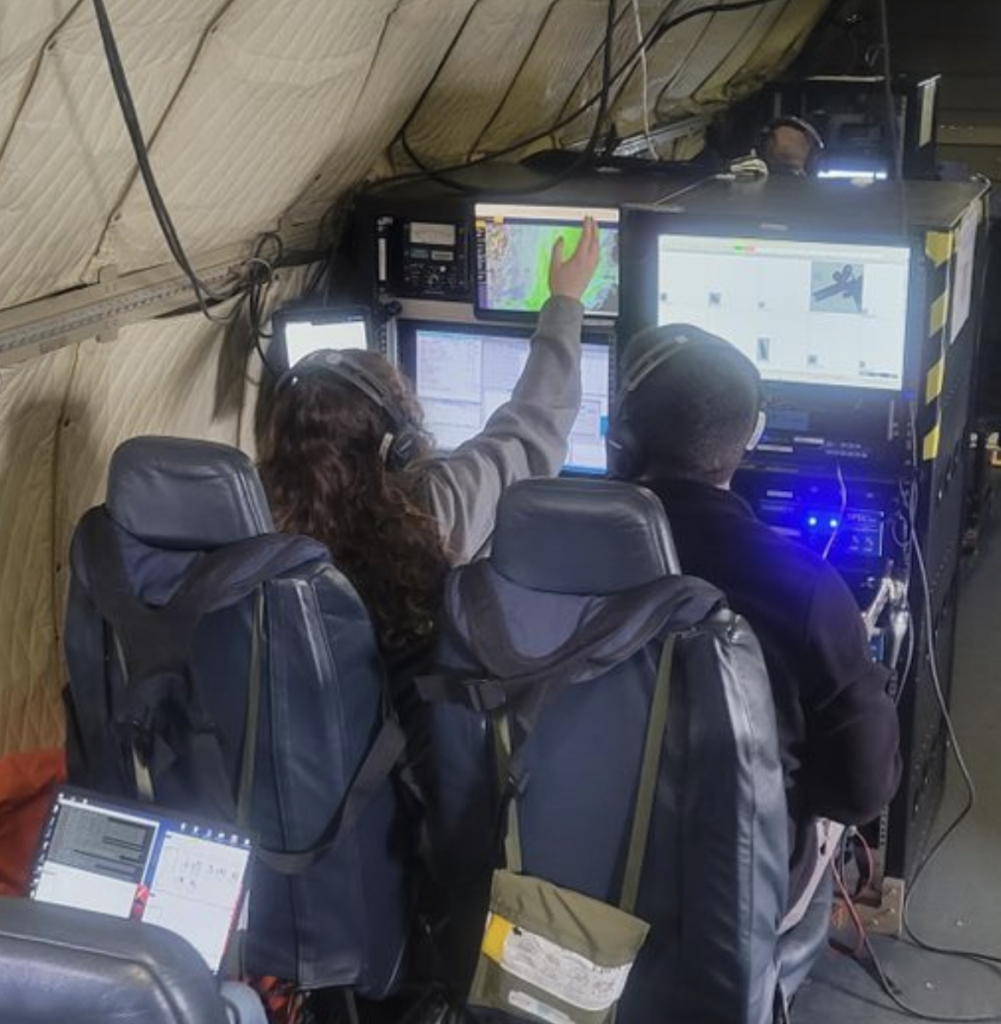

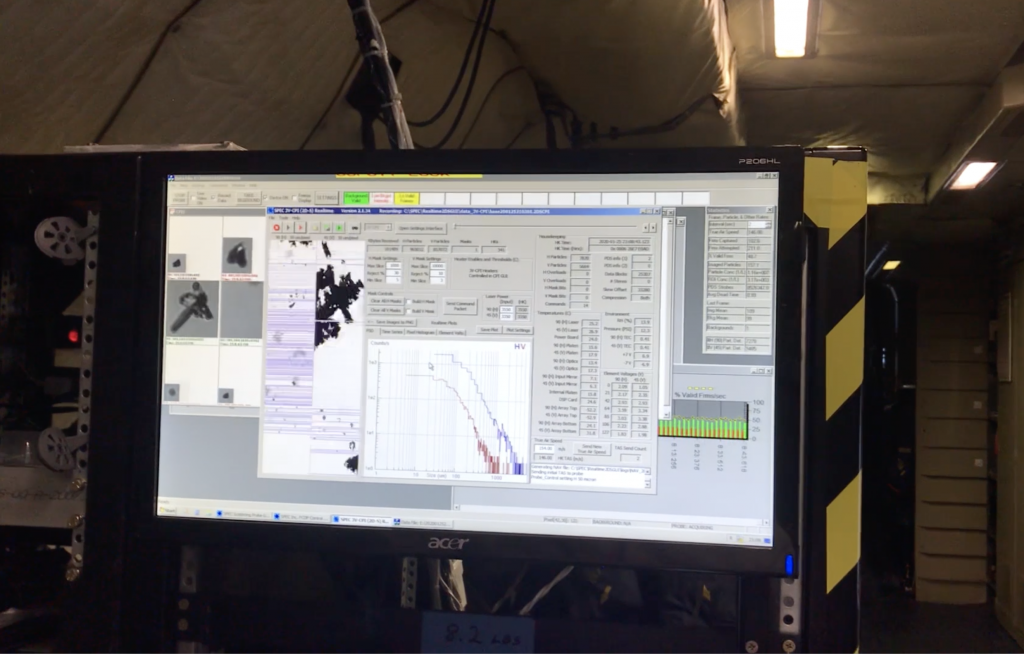

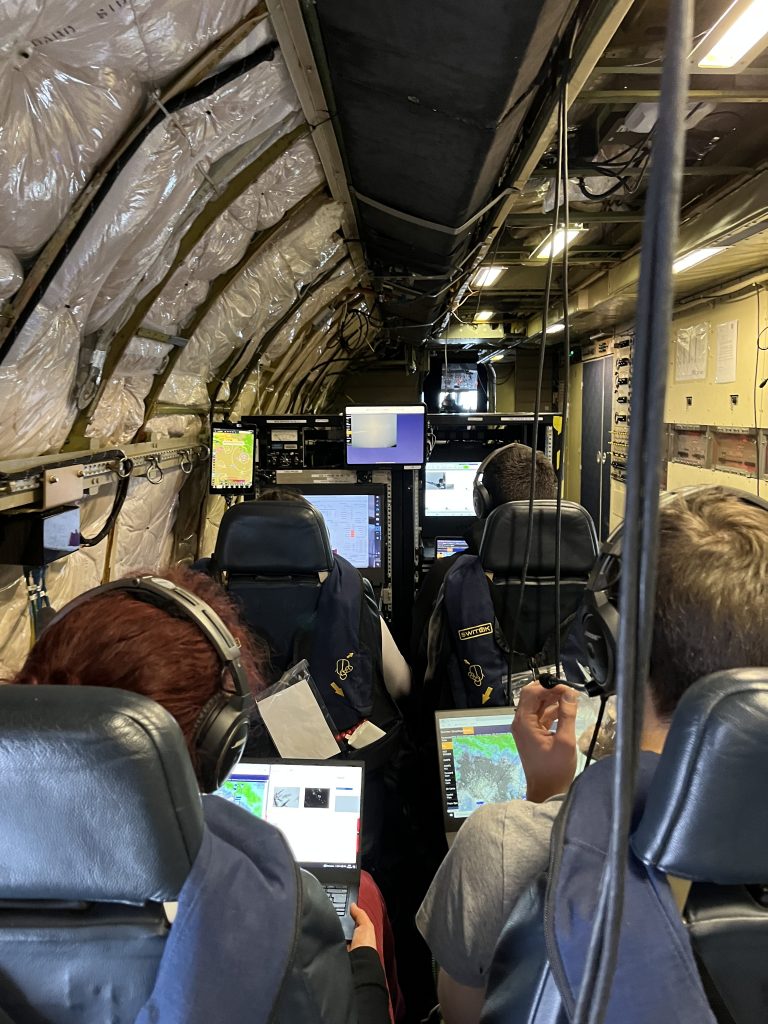

The P-3 is an impressive plane, and it has to be for the level of science occurring on board. Instead of rows upon rows of seats, the body of the plane is almost filled with monitors and computers, showing real time data collection from the instruments attached to the underside of the plane – in-situ probes.

“We’re basically looking at every possible aspect of a cloud,” said Christian Nairy.

Nairy and his colleague, Jennifer Moore, are both Microphysical Probe Operators for the University of North Dakota. They were two of the scientists aboard the P-3 during this flight, watching and gathering data from 10 instruments.

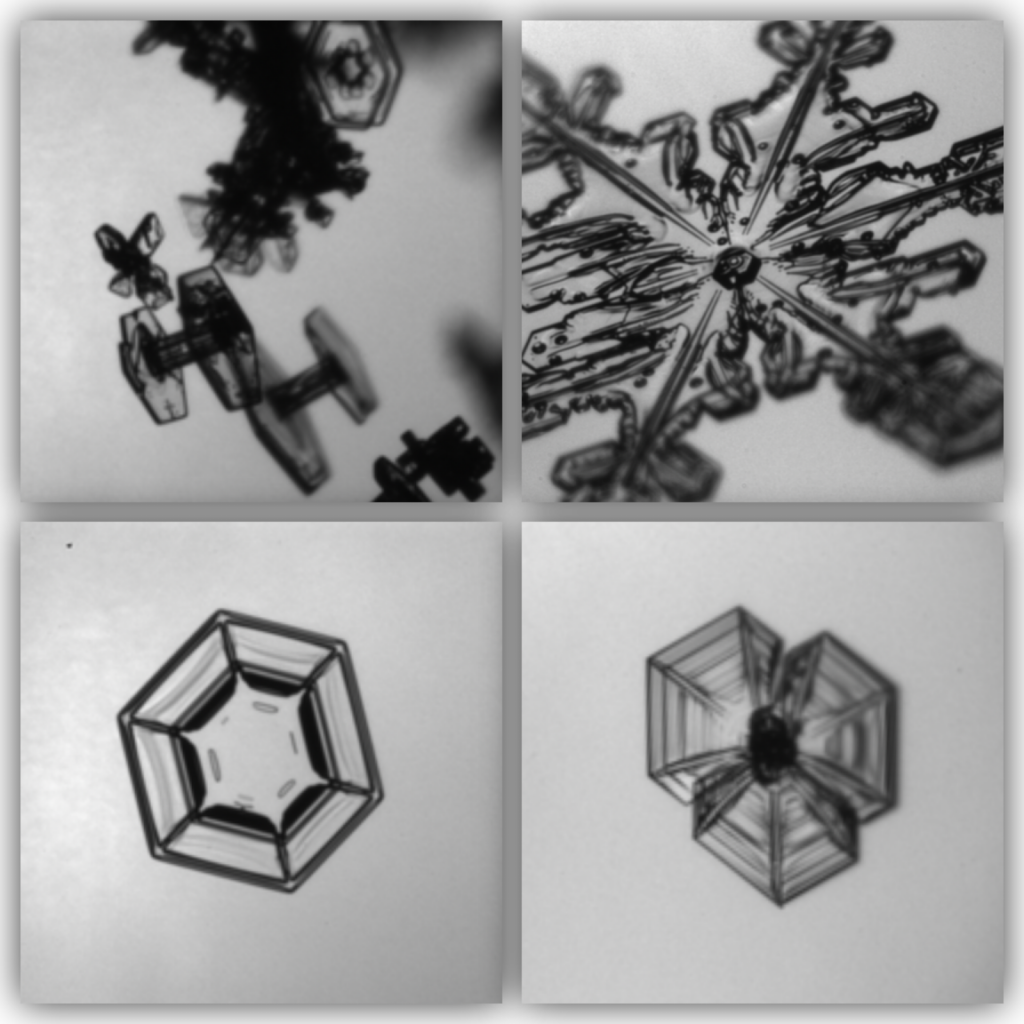

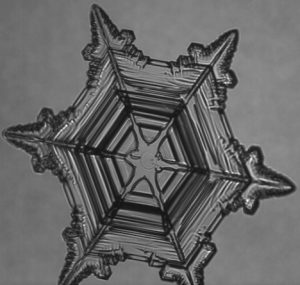

These probes measured several forms of precipitation, from detecting icing and supercooled water to looking at the shape of the actual liquid and ice particles.

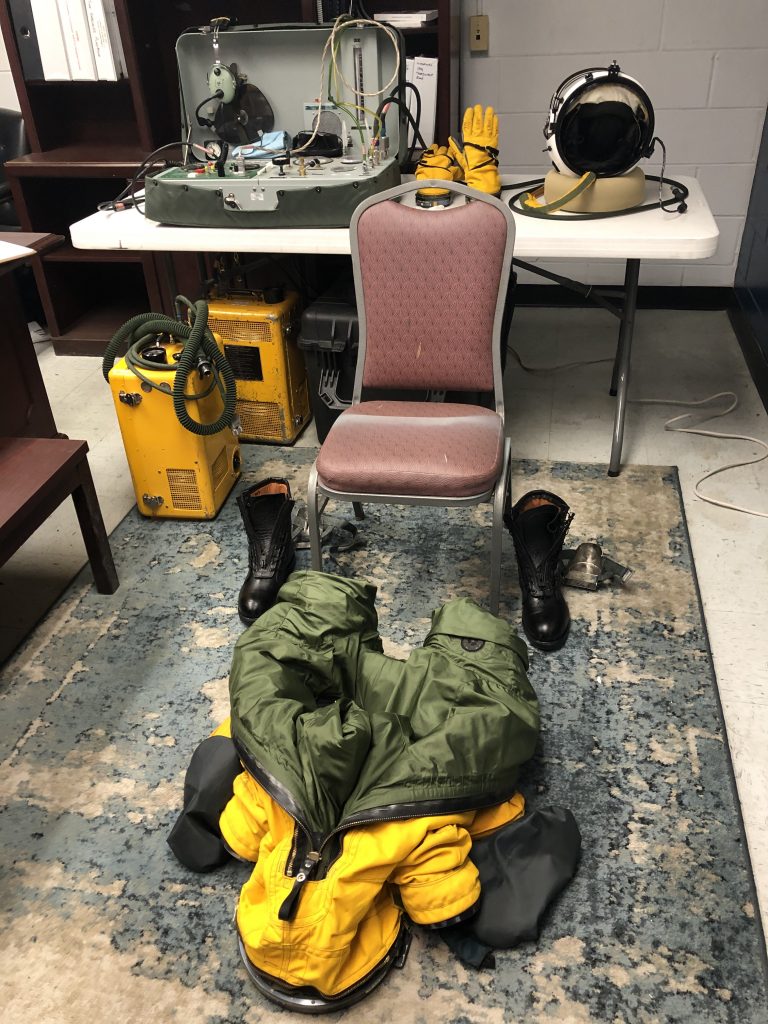

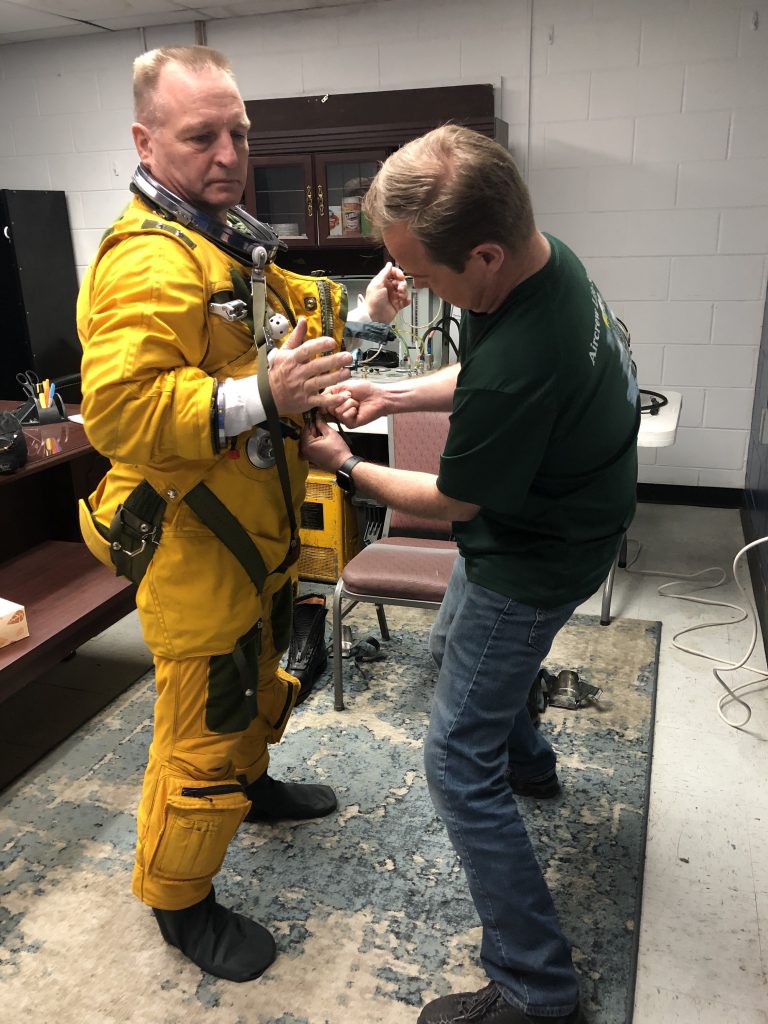

The P-3 is designed differently than most other commercial aircraft to allow for the data to be collected. It can fly long distances which allows it to transit winter storms to sample multiple parts of the storm as it evolves. It also can fly through supercooled water, which is common between 0°C and -20°C and is important when studying the processes of winter storms.

The plane is also increasingly louder than anything you’d experience on the everyday flight. It’s important for the scientists to keep in communication though, so each person on the flight is hooked up to headsets, constantly switching in and out of talking, frequently asking questions like “what habits are we seeing?” and “what does the cloud look like?” and “what are we seeing on the probes?” The scientists respond to the probed questions with descriptions of the data while the instruments measure in real time.

Throughout this flight, I figured out another calming trick – knowing what exactly is causing the turbulence is as logical an explanation as you can get. How can I petition for these probes to be on all commercial flights?

“Once you understand what turbulence is, how it’s normal, what is causing it, and how aircraft are built to withstand so much more than it actually takes on, you feel better about it,” Nairy said.

“You just kind of get used to it, and now I find it relatively funny,” Moore said, imitating bobbing up and down on the bumpy flight.

Though turbulence may be an inherently frightening or uncomfortable experience, there are real explanations as to why it is happening. So next time you experience turbulence – or for that matter, next time you experience a snowstorm from the ground – thank the scientists completing research from above.

If not from me, take it from the experts:

“Relax, enjoy the flight, and ask lots of questions,” McFarquhar said.