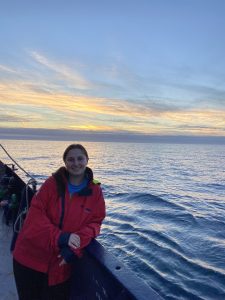

By Mara Freilich, Postdoctoral Fellow at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. // ABOARD THE SALLY RIDE //

While doing oceanographic fieldwork, we live and work on the ship. This is the second week that we have been at sea. While there is a rhythm to life at sea, every day is different. Since we are studying ocean dynamics that change quickly, we sample adaptively, meaning that we adjust when and where we sample to follow quickly moving ocean features. I am a postdoctoral fellow at University of California, San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography. I am working on sampling biological communities to understand how ocean currents, particularly a type of current called submesoscale that spans up to 6.2 miles, or 10 kilometers, across, affect plankton, which form the base of the food web in the ocean. We work as a team on the ship, and I work most closely with the biological sampling team: Kelly Luis (NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory), Sarah Lang and Pat Kelly (University of Rhode Island), Dante Capone (UC San Diego), and Élise Beaudin (Brown University).

There is no typical day, but here’s a look at one “day in the life” of the S-MODE field campaign.

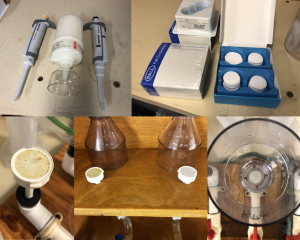

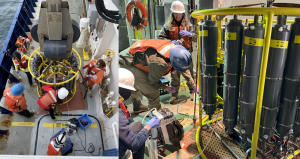

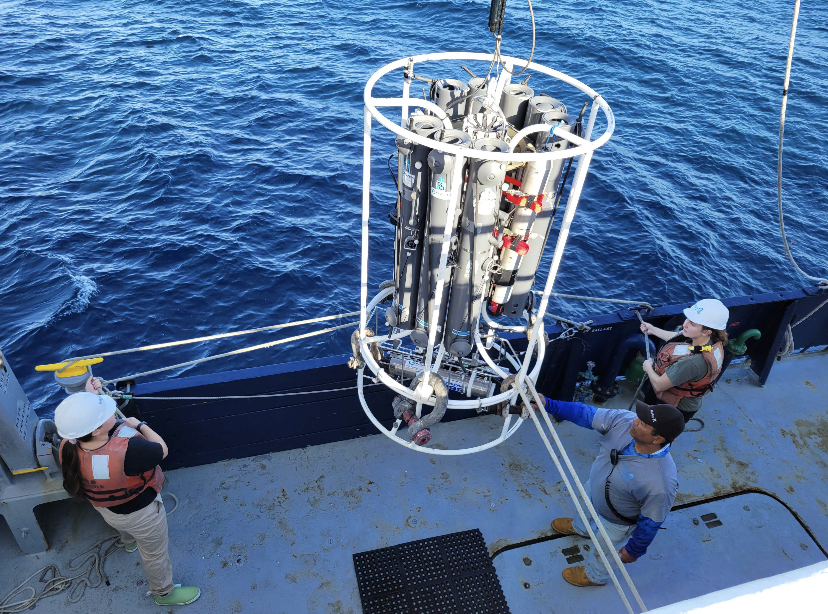

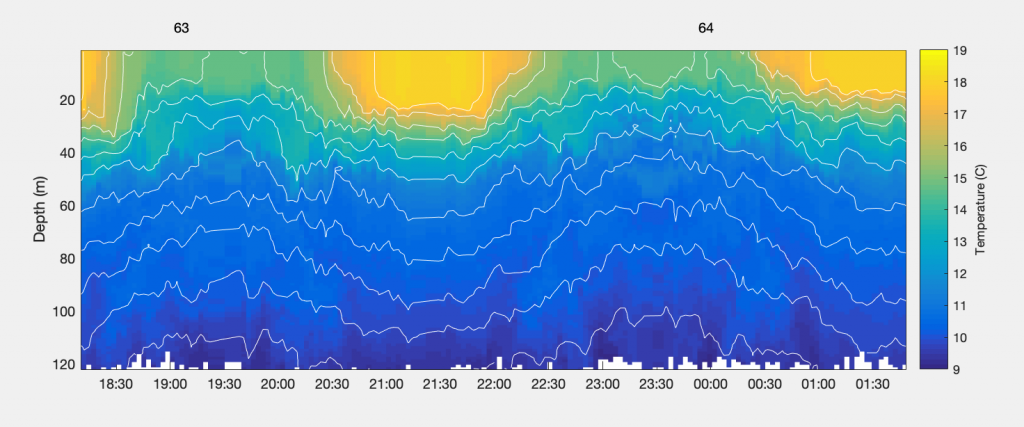

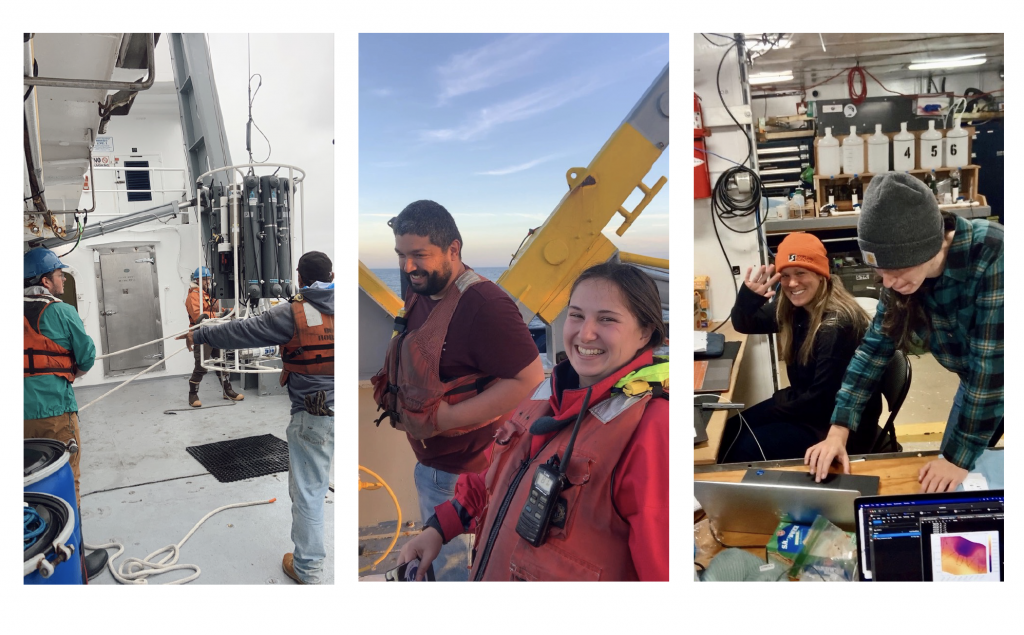

Early morning: I woke up at 2:45 am this morning to plan biological sampling. We aimed to do a Conductivity, Temperature, and Depth (CTD) cast at 5 am. A CTD cast involves lowering a scientific instrument through the water that measures a range of physical and biological variables and that can close bottles to bring water from depth onto the ship. When I woke up, I learned that overnight, Sarah had spotted a submesoscale eddy in the observations. I looked at the new data and agreed that this was exactly the type of ocean current we had been looking for and charted a course to cross through it again. Once I had the plan, I sent waypoints to the captain and mates who drive the ship. Elise, Kelly, Dante and I started sampling surface water to study the biological communities there. When we got the location that we had planned for a CTD cast, we sampled water from the cast and started a 24-hour experiment to measure growth and grazing rates. This allows us to investigate the role of ocean physics and community composition on ocean food webs. We finished processing the samples just in time for a breakfast of croissant and eggs.

Late morning: After a quick nap, I did some data analysis. We are constantly collecting and analyzing data to figure out next steps. Right after lunch (vegetable soup and cheese bread), there was a fire drill. There is a drill every week to keep the scientists and crew in practice in case of a real emergency.

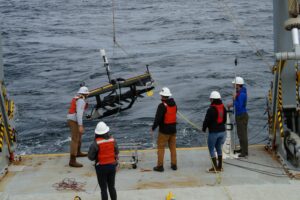

Afternoon: This afternoon we deployed nine autonomous vehicles from the ship. Autonomous vehicles are ocean robots that sample alongside us to give more information. While outside doing this, we saw a whale and took a moment to watch as it swam near the ship!

We also had a Zoom meeting with the whole project team, including the pilots for the autonomous vehicles who work from land, scientists working with instruments on planes that fly over the experiment area every day, and scientists involved in the project in other ways, including numerical modeling. We all discussed our interpretations of what we were seeing and the plan for the next 24 hours.

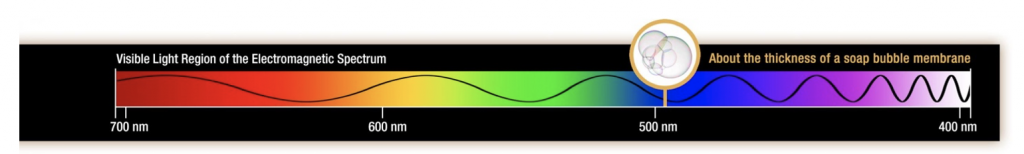

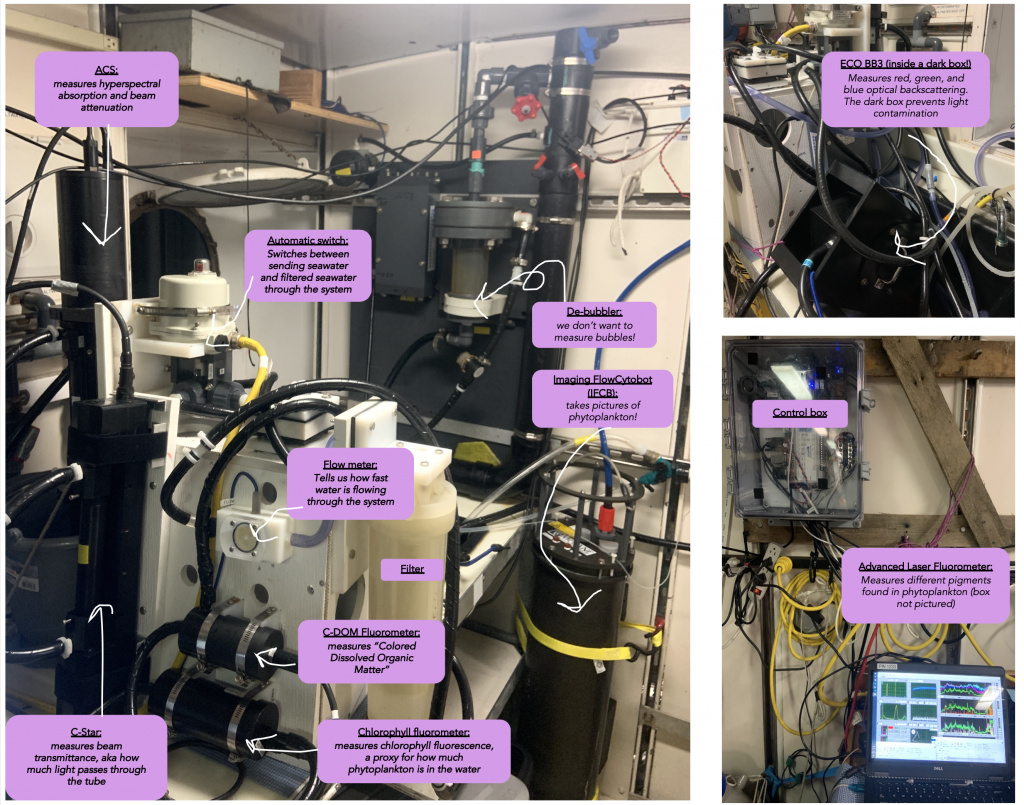

Evening: After dinner, I helped Sarah calibrate one of the instruments that measures the way that light passes through water, called an AC-S (Spectral Absorption and Attenuation Sensor). This instrument tells us about the biological communities in the water, which absorb and scatter light. (Think about a pond with lots of algae that turns green). While the instruments collect data continuously, we have to maintain them to get good quality data. I took a shower and went to sleep after a productive day. Our cabins are on the deck above the spaces where we work and eat. I share my cabin with Kelly. We have bunk beds. Before going to sleep, I made a plan for tomorrow, but of course it might change depending on how the ocean currents change overnight!