When a deadly landslide killed nearly 100 people and forced the evacuation of 75,000 in Guatemala on May 30, NASA carefully documented it. And when more than 300 other rain-triggered landslides pulled the Earth out from beneath towns and villages in China, Uganda, Bangladesh, Pakistan and other countries in 2010, NASA researched and documented each one.

Sudden, rain-induced landslides kill thousands each year, yet no one organization had consistently catalogued them to evaluate historical trends, according to landslide expert Dalia Kirschbaum of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. Three years ago, Kirschbaum set out to change that by creating a searchable inventory of landslides specifically triggered by rain.

WhatOnEarth spoke with Kirschbaum to understand how this tool might tell us more about when and where landslides are most likely to occur.

WhatOnEarth: What is a landslide?

Kirschbaum: Landslides occur when an environmental trigger like an extreme rain event — often a severe storm or hurricane – and gravity’s downward pull sets soil and rock in motion. Conditions beneath the surface are often unstable already, so the heavy rains or other trigger act as the last straw that causes mud, rocks, or debris — or all combined — to move rapidly down mountains and hillsides. Unfortunately, people and property are often swept up in these unexpected mass movements.

Landslides can also be caused by earthquakes, surface freezing and thawing, ice melt, the collapse of groundwater reservoirs, volcanic eruptions, and erosion at the base of a slope from the flow of river or ocean water. But torrential rains most commonly activate landslides. Our NASA inventory only tracks landslides brought on by rain.

WhatOnEarth: What prompted you to develop the NASA landslide inventory?

Kirschbaum: The project was initially meant to evaluate a procedure for forecasting landslide hazards globally. Studying landslide hazards over large areas is a thorny, complicated task because data collection is not always accurate and complete from one country to another. Improving our record-keeping is a first step in determining how to move forward with landslide hazard and risk assessments.

As a byproduct, we knew the catalog would provide information on the timing, location, and impacts of the landslides, which is valuable for exploring the socio-economic effects of these disasters. The International Disaster Database, the largest of its kind, often does not record smaller landslide events or detail their human or property toll.

Each one of our landslide entries contains information on the date of the event; details about the location; the latitude and longitude; an indication of the size of the event; the trigger; economic or social damages; and the number of fatalities.

WhatOnEarth: How is a landslide inventory useful or important?

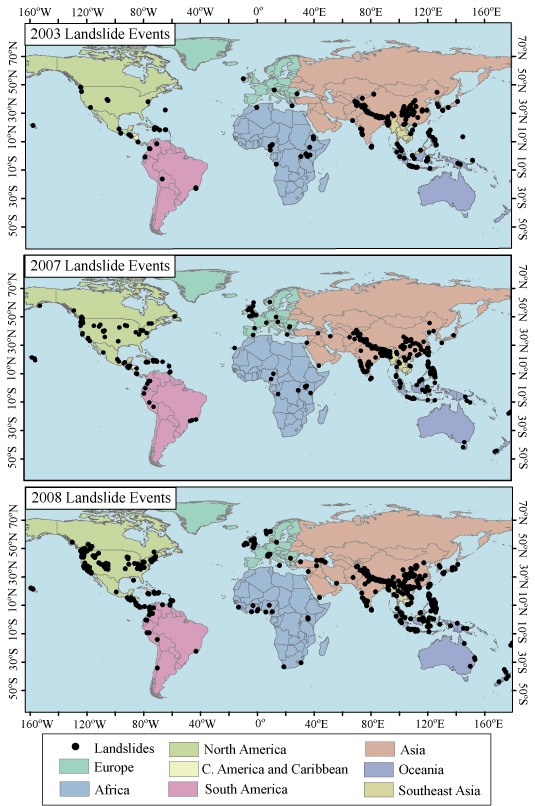

Kirschbaum: As the catalog of events grows, we’ll be able to extract more and more information about which countries have the highest number of landslide reports, highest number of fatalities, etc. We can also break down events by region, season, and latitude, which helps us identify some large-scale patterns. Though the database is limited by occasional reporting biases and incomplete data, the catalog indicates that the highest reported number of rainfall-triggered landslides and fatal landslides occur in South and Southeastern Asia.

We also believe that in the longer term, the catalog will enable us to identify patterns in the global and regional frequency of landslides with respect to El Nino and related climate effects.

WhatOnEarth: Have you used satellite observations for the inventory?

Kirschbaum: No. In a few instances we’ve been able to obtain satellite images  over an area where a landslide is clearly visible. However, landslides typically occur over small areas. Satellites cannot generally “see” such fine ground details or do not pass over the affected area with the frequency necessary to capture when the landslide occurred.

over an area where a landslide is clearly visible. However, landslides typically occur over small areas. Satellites cannot generally “see” such fine ground details or do not pass over the affected area with the frequency necessary to capture when the landslide occurred.

We hope to use satellite imagery, for example from NASA’s Earth Observing 1 (EO-1) satellite, to evaluate the location and area of some larger landslides. This remains a work in progress.

WhatOnEarth: So, if satellites can’t yet help you track landslides, how do you analyze each landslide event?

Kirschbaum: We have searched online literature – sources such as news reports, online journals and newspapers, and disaster databases — for the years 2003 and from 2007 to the present. The landslide inventory is only as good as the availability and accuracy of the reports and sources used to develop it. The work can be tedious and time-consuming, so we’ve enlisted the help of several excellent graduate students to keep the inventory updated over the past three years.

Our database tries to capture as many rainfall-triggered landslides as possible, but this is often difficult due to limitations in reporting of landslide hazards. The accuracy and completeness of details surrounding an event — especially when many landslides are triggered from a very large rainfall event over a broad area– can be less than informative so we are continually trying to improve the cataloguing effort. At the end of this year we’ll have a five-year record of events which will provide us more information to identify global trends.

WhatOnEarth: Is the NASA’s landslide inventory only available to lay people?

Kirschbaum: Our compilation methods were published in a scientific journal last year, and the actual inventory is now openly available to anyone on the Web. We’ll be posting the inventory from January through June 2010 shortly.

Image Information: A massive landslide covered the Philippine village of Guinsaugon, in 2007, killing roughly half of the 2,500 residents. Credit: U.S. Marine Corps./ Lance Cpl. Raymond Petersen III (top). A map of landslide events in 2003, 2007, and 2008. Credit: NASA/Dalia Kirschbaum (above right).

— Gretchen Cook-Anderson, NASA’s Earth Science News Team