Last week, we posted our first mystery sound in our latest installment of “What on Earth is That?”> We had some interesting guesses; one reader guessed the noisemaker was an earthquake and another guessed it was a calving ice. The answer is somewhere in the middle.

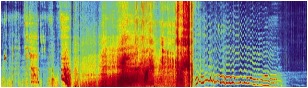

Giant icebergs may sink ships, but they also have their weaknesses. The sound you heard is the seismic signal recorded in October 2005 when a monstrous iceberg drifting off the coast of Antarctica’s Cape Adare crashed into the previously unknown Davey Shoal and broke apart. (Science News covered the collision in this July article.) The full length of the audio file, sped up by a factor of 100, can be heard below. Within just 90 seconds, you can experience the full 2.5-hour event.

The “tap, tap, tap” is from cracks propagating through the massive chunk of ice. The effect is similar to what you hear if you drop ice cubes into a glass of water. The cracking noise crescendos until about 1:15, followed by a subtle hum resembling a muffled chain saw. That noise, from the phenomenon of ice pieces rubbing against each other, becomes most noticeable after the breakup. The same saw-like noise heard prior to 1:15 is thought to be the bottom of the berg rubbing on the shoal.

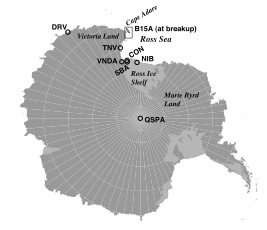

The audio comes from a study published June 18 in Journal of Geophysical Research. Looking at images from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer on NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites, the team noticed that between 1989 and 2005, at least three large bergs drifting off Cape Adare had suddenly stopped and broke apart. To discover the cause behind the bergs’ unusual behavior, the team turned to an iceberg called B15A.

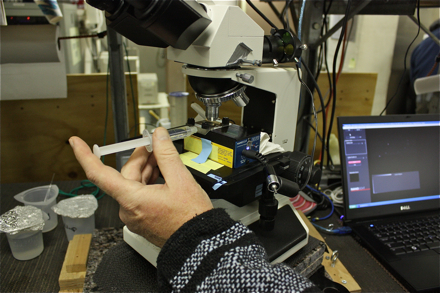

Fortunately, plenty of information about the behemoth berg, which measured about 820 feet vertically and spanned some 75 miles by 19 miles, was available. Before the breakup, scientists had deployed an instrument package on B15A that included GPS and a seismometer. Later, a separate research group mapped the seafloor topography within the same area. “We knew from breakup that there ought to be something there,” said Seelye Martin, of University of Washington in Seattle, who led the study.

Fortunately, plenty of information about the behemoth berg, which measured about 820 feet vertically and spanned some 75 miles by 19 miles, was available. Before the breakup, scientists had deployed an instrument package on B15A that included GPS and a seismometer. Later, a separate research group mapped the seafloor topography within the same area. “We knew from breakup that there ought to be something there,” said Seelye Martin, of University of Washington in Seattle, who led the study.

Overlaying the satellite images on the seafloor map, researchers recreated the series of events. On October 28, the berg hit the top of an underwater shoal 5.6 miles long and 705 feet below the surface at its highest point. The seismic information, heard in this post, matched the collision observed in the satellite imagery. Listening to the seismic music of the Earth is not new; geologists have long listened to the “rock music” of seismic waves from earthquakes. “But the iceberg has a very different signature,” Martin said. “Earthquakes sound like a big boom or slip, while in this case you can actually hear something breaking up.”

So what does it all mean? “It’s an interesting result, but it’s not a world changer,” Martin said. “We now know a little more about the obstacles — and sound — of some ill-fated icebergs leaving the Ross Sea.”

— Kathryn Hansen, NASA’s Earth Science News Team