Our exploration future is focused on the goal of sending humans beyond Earth orbit. This is an incredible aim and the International Space Station has an important role to play in the achievement. If you are following this blog and the stories published on the International Space Station Research and Technology Website, you already know of many investigations that support NASA’s objective. In fact, the very experience of living on the space station can provide important insight into human health, leading to benefits for future explorers.

One aspect of long-duration spaceflight you may not have considered is the experience of isolation that can impact the psychological well being of crewmembers. Those lucky enough to experience interplanetary travel will be cut off from their families, homes, and even their planet. As the explorers travel, even the comfortingly familiar green and blue globe of Earth will resemble a feint blue dot.

A recent crew survey found that astronauts reported one area of spaceflight they found particularly enriching involved their perception of the Earth. The flip side to this finding is the implication that the lack of an Earth view may negatively impact crew psychological well being. To seek verification of this emotional tie to a view of our planet, my colleagues and I chose to examine available data from the Crew Earth Observations or CEO. The goal was to see if there was a correlation between crew photography and mental well being based on the frequency of self-initiated images vs. those mandated by scientific directives.

Astronaut Jeff Williams prepares to photograph

the Earth from the Zvezda Service Module

aboard the International Space Station.

(NASA image)

These images reside in an online collection of imagery called the Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth. In the recently published paper, Patterns in Crew-Initiated Photography of Earth from ISS—Is Earth Observation a Salutogenic Experience?, we looked at the photos taken between Expedition 4 and Expedition 11. This duration spanned from December 2001 to October 2005 and provided 144,180 Earth images to review. Of these photos, 15.5% were taken by space station crewmembers in response to requests by scientists. This means that the other 84.5% were crew-initiated photographs.

This crew-initiated image of São Paulo, Brazil, at night is an example of photography using a

homemade tracking system to capture long-exposure images under low light conditions,

which was assembled by astronaut Don Pettit.

(NASA image ISS006E44689)

Upon examining the images, the data showed that crewmembers took more photos when they had free time. When ramping up for increased activity on orbit, voluntary photography declined, whereas during reduced times of work, imagery increased. Likewise, if the crewmember was already at the window with the camera in hand for a CEO objective, they were more likely to continue photographing the Earth. The longer the individual was on station the more frequently they photographed the Earth, likely due to task familiarity and general acquaintance with station life.

Surprisingly, there was no connection between crewmember photography and areas of specific interest—such as hometowns or birthplaces. This may have to do with the fact that in this study these places were chosen by the researchers, rather than by the crewmembers themselves. Perhaps a future examination delving into the crew’s preference, as compared with the available data, may show alternate findings.

There was also an element of challenge via Earth photography, including learning and perfecting a new skill with the station cameras, that appears to have engaged the crew’s interest. For instance, the choice to shoot more frequently with the 800mm lens, a much more difficult focal length to manage and control, implies enjoyment. For the same reason someone may pick up a crossword puzzle, those on the space station may seek to fill time with tasks of mental dexterity. This implies the benefits of providing extended exploration participants with not only a creative outlet, but objectives that require intellectual acuity.

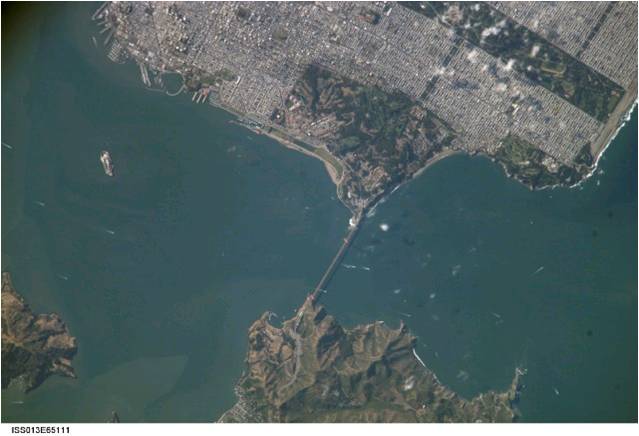

This view, taken with using the 800-millimeter lens combination, shows a portion of an image

of the Golden Gate Bridge, San Francisco, California, taken during Expedition 13 by

astronaut Jeff Williams from aboard the International Space Station.

(NASA image ISS013E65111)

When you consider that a round trip mission to Mars could last as long as three years, it is not hard to understand why we are concerned about possible negative psychological impacts of isolation and confinement. As for all our human exploration risks, we are seeking ways to mitigate the impacts. The significantly large percent of images that were self-initiated in this study indicates that—time permitting—viewing, photographing, and subsequently sharing pictures of Earth is important to crewmembers. Likewise, providing challenging, enjoyable, and comforting leisure activities for the crew may be the key to securing long-term mental health while they are far from home.

Julie A. Robinson, Ph.D.

International Space Station Program Scientist