In today’s A Lab Aloft, guest blogger Liz Warren, Ph.D., recalls the inspirational contributions and strides made by women in space exploration and International Space Station research.

This month we celebrate the anniversaries of three “firsts” for female space explorers. On June 16, 1963, Valentina Tereshkova of the Soviet Union became the first woman in space. Then on June 18, 1983, Sally Ride became America’s first woman in space, followed by Liu Yang as China’s first woman in space on June 16, 2012. Though their flight anniversaries are not in June, I would be remiss if I did not mention the first European woman in space: Helen Sharman in 1991; the first Canadian woman: Roberta Bondar in 1992; and the first Japanese woman: Chiaki Mukai in 1994.

At the Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center in Star City, Russia, Dec. 2, 2010, NASA astronaut Cady Coleman (right), Expedition 26 flight engineer, meets with Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman to fly in space, on the eve of Coleman’s departure for the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, where she and her crewmates, Russian cosmonaut Dmitry Kondratyev and Paolo Nespoli of the European Space Agency launched Dec. 16, Kazakhstan time, on the Soyuz TMA-20 spacecraft to the International Space Station. Tereshkova, 73, became the first woman to fly in space on June 16, 1963, aboard the USSR’s Vostok 6 spacecraft. (NASA/Mike Fossum)

Each of these milestones built upon each other by inspiring the next wave of female explorers, continuing through today with the women of the International Space Station and beyond. With this in mind, I’d like to take a moment to celebrate women in space and highlight those with a connection to space station research. It is amazing to me to see just how connected these seemingly separate events can be. The steps of the intrepid explorers who engage in space exploration set the course for future pioneers, blazing the trail and providing the inspiration for those who follow.

To date, 57 women including cosmonauts, astronauts, payload specialists and foreign nationals have flown in space. Our current woman in orbit is NASA astronaut Karen Nyberg, working aboard the space station as a flight engineer for Expeditions 36 and 37. While Nyberg lives on the orbiting laboratory for the next six months, she will perform experiments in disciplines that range from technology development, physical sciences, human research, biology and biotechnology to Earth observations. She also will engage students through educational activities in addition to routine vehicle tasks and preparing her crewmates for extravehicular activities, or spacewalks.

NASA astronaut Karen Nyberg performs a test for visual acuity, visual field and contrast sensitivity. This is the first use of the fundoscope hardware and new vision testing software used to gather information on intraocular pressure and eye anatomy. (NASA)

Many of the women who have flown before Nyberg include scientists who continued their microgravity work, even after they hung up their flight suits. In fact, some of them are investigators for research and technology experiments recently performed on the space station. Whether inspired by their own time in orbit or by the space environment, these women are microgravity research pioneers ultimately looking to improve the lives of those here on Earth.

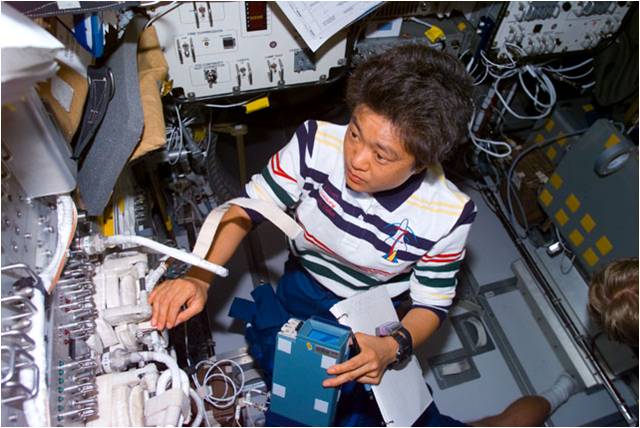

Chiaki Mukai, M.D., Ph.D. of the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency, for instance, served aboard space shuttle missions STS-65 and STS-95. She now is an investigator for the space station investigations Biological Rhythms and Biological Rhythms 48, which look at human cardiovascular health. She also is the primary investigator for Hair, a study that looks at human gene expression and metabolism based on the human hair follicle during exposure to the space station environment. Myco, Myco 2, Myco 3, other investigations run by Mukai, look at the risk of microorganisms via inhalation and adhesion to the skin to see which fungi act as allergens aboard the space station. Finally, Synergy is an upcoming study Mukai is leading that will look at the re-adaptation of walking after spaceflight.

STS-95 payload specialist Chiaki Mukai is photographed working at the Vestibular Function Experiment Unit (VFEU) located in the Spacehab module. (NASA)

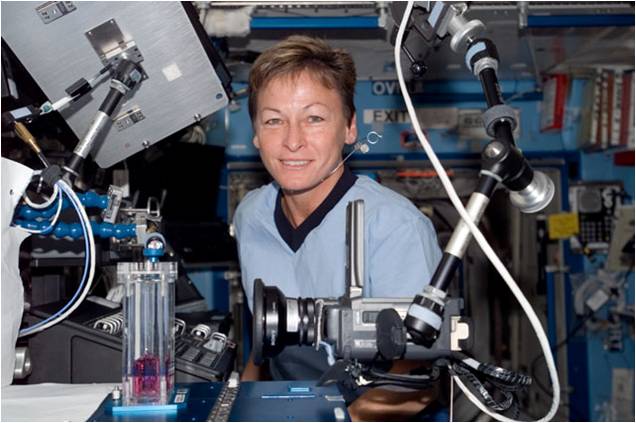

Peggy Whitson, Ph.D. served aboard the space shuttle and space station for STS-111, Expedition 5, STS-113, and Expedition 16. She also is the principal investigator for the Renal Stoneinvestigation, which examined a countermeasure for kidney stones. Results from this science have direct application possibilities by helping scientists understand kidney stone formation on Earth. Whitson, who blogged with A Lab Aloft on the importance of the human element to microgravity studies, also served as the chief of the NASA Astronaut Office at the agency’s Johnson Space Center in Houston from 2009 to 2012.

Expedition 16 Commander Peggy Whitson prepares the Capillary Flow Experiment (CFE) Vane Gap-1 for video documentation in the International Space Station’s U.S. Laboratory. CFE observes the flow of fluid, in particular capillary phenomena, in microgravity. (NASA)

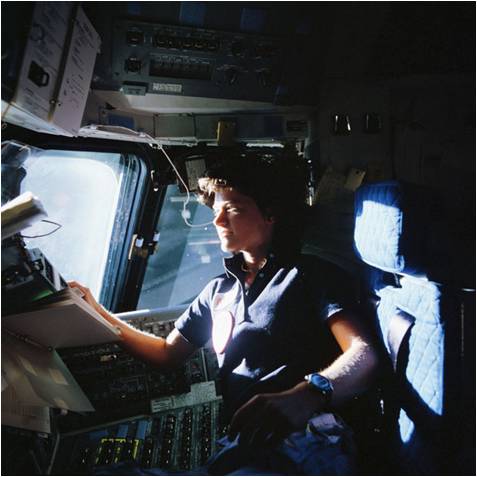

Sally Ride, Ph.D. (STS-7, STS-41G) initiated the education payload Sally Ride EarthKAM, which was renamed in her honor after her passing last year. This camera system allows thousands of students to photograph Earth from orbit for study. They use the Internet to control the digital camera mounted aboard the space station to select, capture and review Earth’s coastlines, mountain ranges and other geographic areas of interest.

Astronaut Sally Ride, mission specialist on STS-7, monitors control panels from the pilot’s seat on space shuttle Challenger’s flight deck. Floating in front of her is a flight procedures notebook. (NASA)

Millie Hughes-Fulford, Ph.D. (STS-40) has been an investigator on several spaceflight studies, including Leukin-2 and the T-Cell Activation in Aging study, which is planned to fly aboard the space station during Expeditions 37 and 38. This research looks at how the human immune system responds to microgravity, taking advantage of the fact that astronauts experience suppression of their immune response during spaceflight to pinpoint the trigger for reactivation. This could lead to ways to “turn on” the body’s natural defenses for those suffering from immunosuppression on Earth.

Hughes-Fulford has been a mentor to me since I was in high school. It was Hughes-Fulford who encouraged me to pursue a career in life sciences, and she also invited me to attend her launch aboard space shuttle Columbia on STS-40, the first shuttle mission dedicated to space life sciences. In fact, STS-40 also was the first spaceflight mission with three women aboard: Hughes-Fulford; Tammy Jernigan, Ph.D.; and Rhea Seddon, M.D.

I followed Hughes-Fulford’s advice, and, years later, I found myself watching STS-84 roar into orbit carrying the life sciences investigation that I had worked on as a student at the University of California, Davis. In the pilot’s seat of shuttle Atlantis that morning was Eileen Collins, the first woman to pilot and command the space shuttle. Our investigation, Effects of Gravity on Insect Circadian Rhythmicity, was transferred to the Russian space station Mir, where the sleep/wake cycle of insects was studied to understand the influence of spaceflight on the internal body clock.

Payload Specialist Millie Hughes-Fulford checks the Research Animal Holding Facility (RAHF) in the Spacelab Life Sciences (SLS-1) module aboard space shuttle Columbia. (NASA)

Women at NASA always have and continue to play key roles in space exploration. Today we have female flight controllers, flight directors, spacecraft commanders, engineers, doctors and scientists. In leadership positions, Lori Garver is at the helm as NASA’s deputy administrator, veteran astronaut Ellen Ochoa is director of Johnson; and Lesa Roe is director of NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Va.

In space exploration and in science, we stand on the shoulders of those who came before us. These women pushed the boundaries and continue to expand the limits of our knowledge. What an incredible heritage for the girls of today who will become the scientists, engineers, leaders and explorers of tomorrow.

Liz Warren, Ph.D., communications coordinator for the International Space Station Program Science Office. (NASA)

Liz Warren, Ph.D., is a physiologist with Barrios Technology, a NASA contractor. Her role in the International Space Station Program Science Office is to communicate research results and benefits both internally to NASA and externally to the public. Warren previously served as the deputy project scientist for Spaceflight Analogs and later for the ISS Medical Project as a science operations lead at the Mission Control Center at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. Born and raised near San Francisco, she has a Bachelor of Science degree in molecular, cellular and integrative physiology and a doctorate in physiology from the University of California at Davis. She completed post-doctoral fellowships in molecular and cell biology and then in neuroscience. Warren is an expert on the effects of spaceflight on the human body and has authored publications ranging from artificial gravity protocols to neuroscience to energy balance and metabolism.