In today’s A Lab Aloft blog entry Camille Alleyne, Ed.D., assistant program scientist for the International Space Station Program Science Office, shares with readers the role of model organisms in microgravity research.

Have you ever thought about why biologists use the term “model organism?” This does not imply that these particular species set an example for the others in their genus. Rather, they have characteristics that allow them easily to be maintained, reproduced and studied in a laboratory. Conducting basic research on model organisms also helps researchers better understand the cellular and molecular workings of the human body, in addition to how diseases propagate. This is because the origins of all living species evolved from the same life process that is shared by all living things.

Model organisms can be plants, microbes (e.g., yeast) or animals (e.g., flies, fish, worms and rodents), all of which are widely studied and have a genetic makeup that is relatively well-documented and well-understood by scientists. Researchers favor these organisms because they grow relatively quickly and have short generation times, meaning that they swiftly produce offspring. They also are usually inexpensive to work with and are quite accessible, making them ideal for experimentation.

Aboard the International Space Station, researchers conducting studies on animal and plant biology disciplines also prefer to use model organisms. In several investigations, scientists use these test subjects to advance their knowledge of the fundamental biological processes, as they are already well-known in the specific species based on ground experimentation.

Researchers use model organisms to study how microgravity affects cells. Examining the impacts of the space environment on an organism’s development; growth; and physiological, psychological and aging processes can lead to a better understanding of certain diseases and issues associated with human health.

Cells behave differently in space than on Earth because the fluids in which the cells exist move differently in the microgravity environment. The fundamental nature of the cell changes, including its shape and structure, how signals pass back and forth between cells, how they differentiate or split, how they grow or metabolize and alterations to the tissue in which cells live. Developmental biologists can learn much from these adaptations.

The Biological Research in Canisters (BRIC) experiment series of space station investigations, for instance, focuses on the area of plant biology. The study uses the thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana) as its model organism. Scientists look at the fundamental molecular biological responses and gene expression of these plants to the microgravity environment. This small, flowering plant already has a well-sequenced genome—meaning researchers already have a map for the heredity of organism’s genetic traits. These traits are what control the characteristics of an organism, such as how it looks, behaves and develops over time.

Thale cress is approximately three- to seven-tenths of an inch tall and can produce offspring in large quantities in about six weeks. It also has the advantage of a small genome size—so it’s not complicated to study—and an abundance of available genetic mutants—which allows for varied areas of research focus. Specifically in the BRIC-16 investigation, Anna-Lisa Paul, Ph.D., and Robert Ferl, Ph.D., at the University of Florida in Gainesville examined the changes in the genome sequencing and DNA of these plants. Results assisted space researchers in understanding how to maintain food quality and quantity for long-duration spaceflights, in addition to how to provide and maintain life-support systems. There also are Earth applications, including understanding basic plant processes that may increase our ability to control more effectively plants for agriculture purposes.

In the area of animal biology, there are numerous investigations that use a variety of model species as subjects. In the Micro-5 investigation, principal investigator Cheryl Nickerson, Ph.D., of Arizona State University—along with co-principal investigators Charlie Mark Ott, Ph.D., of NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston; Catherine Conley, Ph.D., at NASA’s Ames Research Center at Moffett Field, Calif.; and Dr. John Alverdy, University of Chicago—use an organism referred to as Caenorhabditis elegans. This human surrogate model helps us better understand the risks of flight inflections to astronauts during long-duration spaceflight.

C. elegans are free-living, transparent nematodes, or roundworms, that live in temperate soil environments. They are inexpensive and easy to grow in large quantities—producing offspring with a generation time of about three days. Members of this species have the same organ systems as other animals, making it a great model organism choice. In this study, C. elegans will be infected with the salmonella (Salmonella typhimurium) microbe, which causes food poisoning in humans and is known to become more virulent in microgravity—meaning it increases its disease causing potential. Studying this host-pathogen combination provided researchers with insight into how this bacterium will respond in space explorers, if infected. The knowledge lays a solid foundation for the development of vaccines and other novel treatments for infectious diseases.

Another model is Candida albicans, which is an opportunistic fungus or yeast that exists in a dormant state in about three of every four people. It has greater potential to become active in individuals with compromised immune systems, hence the term “opportunistic.” When active, this pathogen causes thrush or yeast infections. Easily mutated, this organism’s genes are readily disrupted for study. Principal investigator Sheila Nielsen-Preiss, Ph.D., of the Montana State University in Bozeman, used this model for the Micro-6 investigation during Expedition 34/35. As in other model organisms, the well-understood genetic makeup of this fungus made it easier for scientists to identify changes that occurred in microgravity. This led to a better understanding or the fungus’ fundamental physiological responses and their ability to cause infectious diseases.

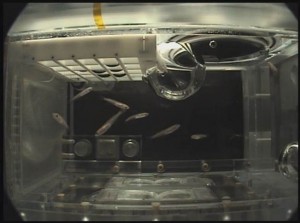

On a larger scale, one of the human body’s major adaptations to spaceflight is the loss of bone mineral density. Understanding the mechanisms by which bones break down and build back up in this extreme environment is critical to human space exploration. In order to understand these phenomena more fully, researchers study Medaka fish (Oryzias latipaes) in the Aquatic Habitat (AQH) aboard the space station.

These model animals found in Asia are used extensively in biological research. They are vertebrates—meaning they have backbones—making them a good choice for studying bone activity. Medaka also have a well-mapped genome, a short gestation period and reproduce extremely easily. They are resilient and can survive in water of various levels of salinity.

In the Medaka Osteoclast investigation, principal investigator Akira Kudo, Ph.D., of the Tokyo Institute of Technology, along with co-principal investigators Yoshiro Takano, DDS, Ph.D., of the Tokyo Medical and Dental University; Keiji Inohaya, Ph.D., of the Tokyo Institute of Technology; and Prof. Masahiro Chatani of the Tokyo Institute of Technology, studied the process by which bone breaks down via the activity of bone cells known as osteoclasts. The transparency of the fish gave researchers a view into the mechanism of this process that would not be possible with other fish species. The goal of this research is to advance our knowledge on human bone health, leading to development of treatments and countermeasures for both astronauts living in space and patients suffering from osteoporosis on Earth.

In the coming year, the space station will add two new facilities as research resources to house a couple of distinct model organisms. The first is a fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) habitat. This type of insect is one of the 1,200 species in the genus of flies that is particularly favorable in genetic research. You may be surprised to know that the genes of D melanogaster are very similar to those of humans. More than half of our genes that map to diseases have been found to match those of fruit flies.

Since fruit flies reproduce quickly and their genome is completely sequenced, they serve as good models to study diseases in a much shorter time than it would take via human research. In the context of human spaceflight, scientists will continue to use fruit flies as a model to test gene expression in the space environment, adding to work done on the space shuttle.

The second habitat coming to the space station will house rodents. Mice (Mus musculus) are the most widely known of the model species in scientific research, because their genetic code and physiological traits are very similar to humans. They are vertebrate mammals with a 10-week generation time. Their genome is very well-sequenced and understood, and they are easy to mutate and analyze.

Mice, more than any of the other animal model organism mentioned here, allow researchers to study beyond just the cellular cycle. They have the opportunity to advance their fundamental understanding of other human systems such as the immune, cardiovascular and nervous systems, to name a few. Mice afflicted with various diseases, including osteoporosis, cancer, diabetes and glaucoma, can lead researchers to findings that advance treatment options.

These developments and findings from past, present and future investigations aboard the space station continue to enable biologists in their studies. As researchers better understand the adaptation of model organisms in a microgravity environment, they can facilitate future ways doctors will manage human health, both in space and on Earth.

Camille Alleyne, Ed.D., is an assistant program scientist for the International Space Station Program Science Office at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. She is responsible for leading the areas of communications and education. Prior to this, she served as the deputy manager for the Orion Crew and Service Module Test and Verification program. She holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Mechanical Engineering from Howard University, a Master of Science degree in Mechanical Engineering (Composite Materials) from Florida A&M University, a Master of Science degree in Aerospace Engineering (Hypersonics) from University of Maryland, and a doctorate in Educational Leadership from the University of Houston.