by Kate Squires / PALMDALE, CALIFORNIA /

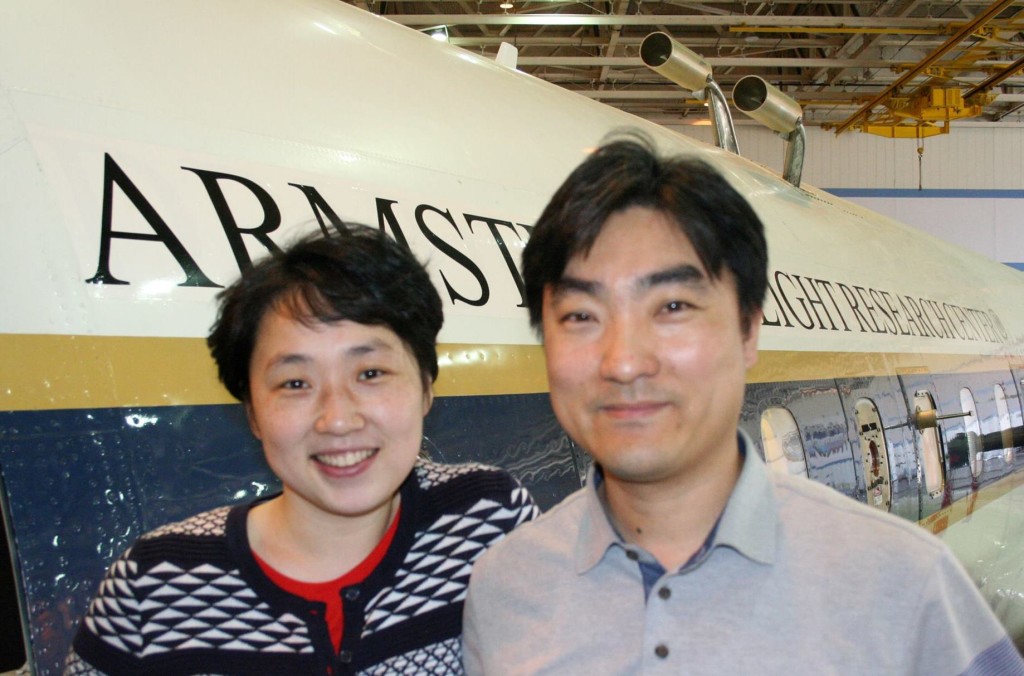

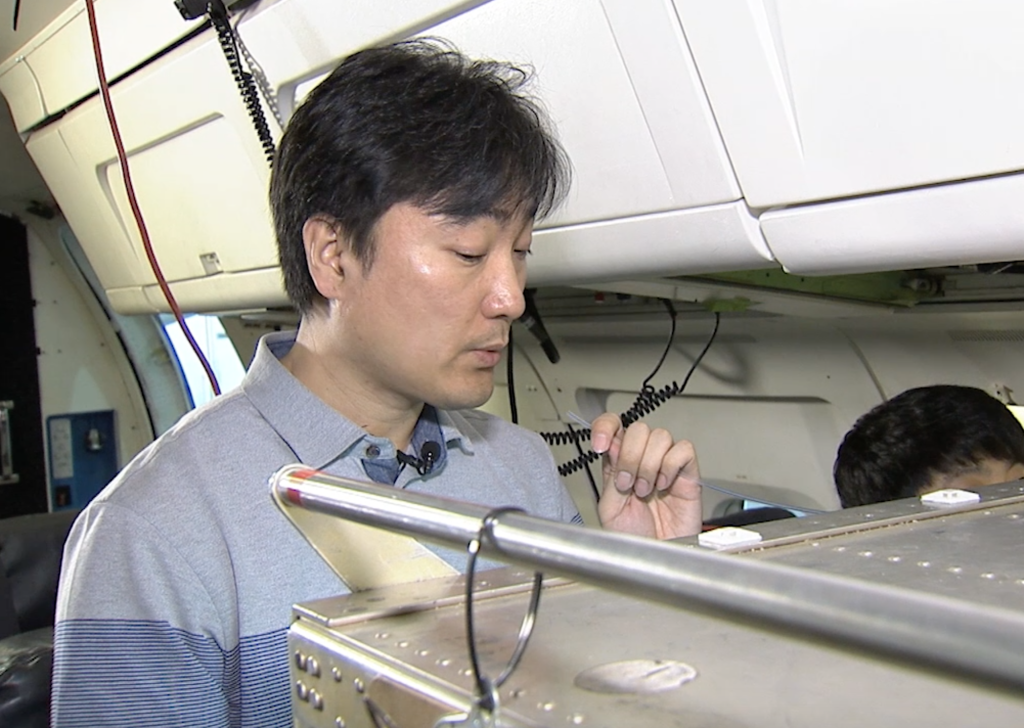

They met at an air quality-monitoring site near downtown Seoul over a decade ago. Now the husband-and-wife team of atmospheric chemists are working together on the KORUS-AQ field experiment that gets underway this week in South Korea. Jeong-Hoo Park is the lead Korean scientist for KORUS-AQ and senior researcher at the National Institute for Environmental Research in Seoul. Kyung-Eun Min, assistant professor at the Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology, leads the K-ACES instrument team participating in KORUS-AQ. We caught up with the couple last week at the Armstrong Flight Research Center Hangar 703 in Palmdale as they checked out instruments being installed on NASA’s DC-8 flying laboratory.

What are the big goals of the KORUS-AQ mission?

Jeong-Hoo Park: The first is to inventory South Korea’s emissions. The second is to study the mechanisms that control air pollution in Korea and then create an efficient strategy to improve air quality using policy. The third goal is to improve the country’s air quality forecasting system. The last is to validate sensors and algorithms for a satellite called Geostationary Environmental Monitoring Spectrometer (GEMS) that will monitor air quality from space after it launches in 2019. The satellite will be identical to NASA’s planned Tropospheric Emissions: Monitoring of Pollution (TEMPO).

Can you describe a particularly bad air quality day that you’ve experienced while in South Korea?

Kyung-Eun Min: I was living in California during my PhD program and went back to visit my mom in South Korea during May. I was hanging out with family, and I looked at the sky and noticed it was gray. It was like that all day long. I said to my mom, “Oh it looks like it’s going to rain soon, but it’s not going to rain.” My mom responded. “No, it’s very sunny today! It’s sky blue!” I said, “No, can’t you see that it’s overcast and gray?” That was the first time I ever realized the daily air quality contrast between Korea and the U.S.

Does South Korea have a warning system to alert its citizens of a bad air quality day?

KEM: When I was in graduate school they only had an alert warning for Asian dust events. These days there is also a pollution forecasting and alert system.

JHP: Yes, we have an air quality forecasting system that is managed by the National Environmental Institute of Research and gives a next-day forecast to the public every day via the news networks. The system warns the public so that they can be better prepared and wear a mask if needed.

Jeong-Hoo, how did you get involved and eventually co-lead the KORUS-AQ mission?

JHP: Before working on KORUS-AQ, I worked at National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. One day I heard about the mission there and was intrigued, so I decided to move back to Korea to manage the mission about a year and a half ago.

What has been the most challenging part of planning the KORUS-AQ mission? The most rewarding?

JHP: The most challenging part of planning was gaining consensus between all of the different organizations. For example, I had to convince the Air Force and related organizations for support of the project.

KEM: The most rewarding part is the opportunity to have the mission take place in South Korea. We have never had such a large and complex mission in our country. It is also rewarding to share this opportunity with our students and let them see how we collaborate and how important our work is.

What first got you interested in this area of research?

JHP: When I was an undergraduate student, I took an air pollution class. I saw that there were a few chemical reactions with some equations that expressed a phenomenon in the air and I was very interested in that because it actually expressed things that are invisible to us. I was so excited and I jumped right into it.

KEM: I’ve always liked atmospheric research because it deals with a global issue. Air doesn’t have any social borders. If something major happens to the air in one country, it crosses to other countries so easily and quickly.

Where did you go to school?

JHP: I went to Yeungnam University in Korea for my undergraduate degree and went to Korea University to study atmospheric chemistry. I went abroad to the United States to the University of California, Berkeley and graduated with my PhD from the Environmental Science Policy and Management Department.

KEM: I went to Korea University for both my bachelors and masters science programs in atmospheric chemistry. I went on to UC Berkeley for my PhD and did postdoctoral work at NOAA.

Did you meet at UC Berkeley?

BOTH: No.

JHP: We met before.

KEM: In a field mission in Korea.

JHP: Fourteen years ago, we met at the field site, which is the same as one of the KORUS-AQ ground sites.

KEM: We met when we were in different groups at the Olympic National Park, which was a ground site for another air quality field study but also one for KORUS-AQ. We started to date each other secretly. Then we ended up pursuing our PhDs together at UC Berkeley. So there was some luck to it, too.

Is there any professional competition between you as husband and wife?

JHP: Well, I will say that we are kind of a synergetic couple because the measurements from our instruments are complementary.

KEM: People think we are a good couple so we are good colleagues, and usually we are. When I did nitrogen oxide studies in graduate school, he was studying volatile organic compounds (VOC). They are good ingredients for trying to understand ozone pollution and complex chemistry, and we collaborated well during that time. Now I’m starting to look at oxygenated VOC’s, so I’m very eager to get his data and analyze it. Sometimes we sit down to have a discussion about the data and come to a point where we have slightly different perspectives, so then we argue sometimes.

BOTH: [Laughing]

JHP: There is no competition.

Do you typically talk about science at home around the dinner table?

KEM: Some couples that work in the same field will not talk about work at home, but we are not like that. We discuss whatever we want. Sometimes it’s about the science. Sometimes it’s about personal life.

JHP: One time we had lunch with a friend. We were discussing general things about life, but then the conversation turned into us having a deep discussion about science. Our friend said, “Why do you talk about science in the middle of lunch? You both are nerdy!”

Do you have any children?

KEM: We have one son, who is seven months old.

Do you want your son to go into the air quality research field?

KEM: Interesting question. We’ve talked about it a lot. In Korean culture, parents expect a lot of their offspring. If he chose atmospheric science as his field of interest then we would probably be very happy, but we don’t want to pressure him into going that direction.

JHP: I agree. I want him to do anything he wants to do.

How will this research help people today and people in the future?

JHP: I hope that the success of the KORUS-AQ mission will provide data that will lead to better emission policies and the best air quality for the next generation, including my son. I hope it will also help further develop the Korean atmospheric research community and push us towards doing more air quality research studies.