by Ellen Gray / GOBABEB, NAMIBIA /

Brent Holben stands in the shade of his car’s hatchback door, squinting at his phone. He’s checking Google Maps. From the dirt parking lot at the Walvis Bay Airport, Namibia, he temporarily has free internet access to the NASA wifi hotspot set up for NASA’s ORACLES airborne science campaign here.

“I don’t want to make a wrong turn,” he says. “Of course out here, that’s pretty hard. There’s not many turns.”

With a trim gray beard and brimmed hat, Holben, a scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, is in charge of the ground sites that will measure aerosols to complement observations made by ORACLES’s two research aircraft.

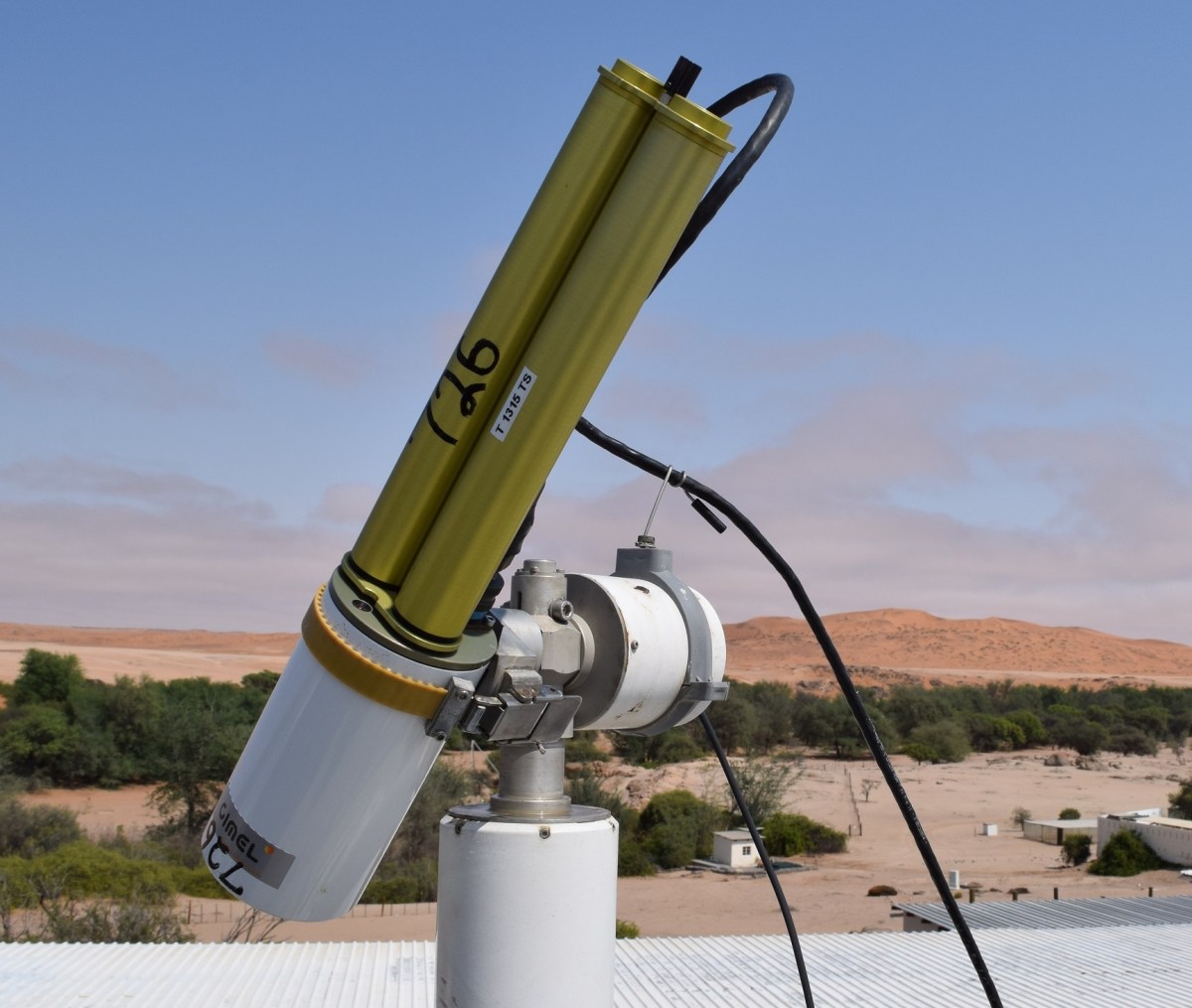

Today, Holben is heading out on a road trip southeast of Walvis Bay to the Gobabeb Research and Training Centre, 40 miles as the crow flies from the coast. There, perched atop a short tower, is one of Holben’s aerosol measuring instruments, a sun photometer that is part of the Aerosol Robotic Network. AERONET, which began in 1992 with two sensors, now has 600 sensors worldwide, but not as many in Africa as Holben would like.

“Africa is a giant place, and it’s underrepresented compared to Europe and the United States.” Holben is the AERONET project scientist.

As ORACLES was being planned to make measurements of aerosols over the southeast Atlantic Ocean from aircraft, he originally drafted plans for two AERONET instruments in Namibia that would study aerosols from the ground. He ended up setting up ten.

A sun photometer has one job: to look at the sun to see how many aerosols are between it and the ground by measuring the light energy that reaches the instrument.

“If the set-up weren’t simple, I wouldn’t do it,” Holben said of the solar-powered instrument.

But simple doesn’t mean without complications. One reason Holben is visiting Gobabeb is because he’s concerned about the instrument shutting down unnecessarily due to the region’s characteristic fog.

The sky is overcast on our drive south, which is not uncommon along the Namibian coast. Early morning fog develops when warm air condenses over the cold ocean water, and then it rolls over the length of the coast and inland. It’s the main source of water for much of the vegetation that grows where it can across the plain.

Not far from the airport the asphalt disappears and we’re driving on a dirt road. To either side the rocky desert is white-beige and flat, textured with small rocks and dotted with occasional buildings that grow fewer and farther between.

On the horizon ahead, great sand dunes appear, first as bumps, then looking like orange mountains. Eventually, a green strip comes into view at the base of the dunes. Holben points out as the green strip resolves into trees. “That’s the river.”

The river is the Kuiseb (pronounced kwee-sib), and it’s dry for most of the year. During the rainy season from November to January or so, it may have water for a few months, replenishing the groundwater for the trees – and everything that eats their leaves – to live on for the rest of the year.

The road turns east and from here parallels the river into the Namib-Naukluft Park and to Gobabeb Centre where it dead-ends. Along the way are the farms of the local Topnaar community, which has lived along the Kuiseb for the past 600 years. Many have day jobs in Walvis Bay to supplement their living. Along the river they raise cattle and other livestock.

“It’s a harsh existence. You’ve got to admire people who eke out a living here,” said Gillian Maggs-Kölling, the Gobabeb Centre’s executive director. The centre is located next to three ecosystems: the rocky plain, the linear oasis of the river, and the 1,000-foot sand dunes that roll into the Sand Sea to the south.

Maggs-Kölling is a biologist, as are most of the 18 researchers and students who live and work there. It’s an international mix, with students from the Namibian University of Science and Technology joined currently by a group from the University of Basel in Switzerland, and a handful of others from various other European and American universities.

The main building with labs and offices is surrounded by a spread of low cottages and gardens of scientific instruments measuring temperature, moisture, and a dozen other things. Completely off-grid, the site is powered by solar panels with the occasional help of a generator.

This is Holben’s third trip to Gobabeb, one each year since setting up the AERONET sensor here.

“We came here because we didn’t have an instrument in this part of the world. The Namib Desert is quite unique because it is influenced by fog,” said Holben. He and the ORACLES team hope to learn how the aerosols they’re measuring affect the fog and the clouds over the ocean.

We meet Monja Gerber, a relatively new technician and Masters student in plant physiology from North West University in South Africa, who is taking care of the instrument this year.

Atop the two-story tower where the AERONET instrument sits, Holben shows Gerber a few maintenance tricks. The instruments tube is open and sometimes spiders or bees like to make homes in them, he points out. Holben shows her how to disconnect the wet sensor that triggers when fog collects on it.

As the day warms, morning fog that rolls in from the coast clears. Using its own GPS location and the time of day to find the sun, the AERONET photometer spins into action.

“We’re looking at two main aerosols in this region. Dust blown from the desert is one, which is actually a very small component. The big one is smoke from fires in central Africa. These are man-made agricultural fires as people clear their land at this time of year,” said Holben.

Westerly winds take the smoke from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zambia, and Angola, and carry it out over the southeast Atlantic, where ORACLES’s two research aircraft measure it to see how the smoke changes sunlight absorption or reflection – important to know for understanding and predicting climate change. That smoke arcs back to Namibia on south-easterly winds.

“We’ve been watching the aerosols day by day for ORACLES,” Holben said of both the measurements here at Gobabeb and the six sensors that are set up in Henties Bay, an hour north of Swakopmund. “Over the last several days, the optical depth went from almost background conditions to – yesterday – moderately high.”

Light scattered by the smoke aerosols makes sunsets here red, Holben added.

The sunset is spectacular. Holben and his son Sam, who accompanied him on the trip, cross the river and climb to the top of the nearby dune to watch. They leave with barely enough time, and Sam, not wanting to miss it, runs ahead and picks the steepest ascent.

Climbing a dune of fine sand is not easy, and he slides down nearly as much as he climbs, but persistence gets him to the top. Holben takes a less-steep approach and settles in for the show.

From the top, the Namibian landscape stretches as far as the eye can see, changing colors as the sun sinks behind the dunes in the west. The stars slowly come out and the Southern Hemisphere constellations brilliantly shine beneath the sweep of the Milky Way.