by Ellen Gray / CHRISTCHURCH, NEW ZEALAND /

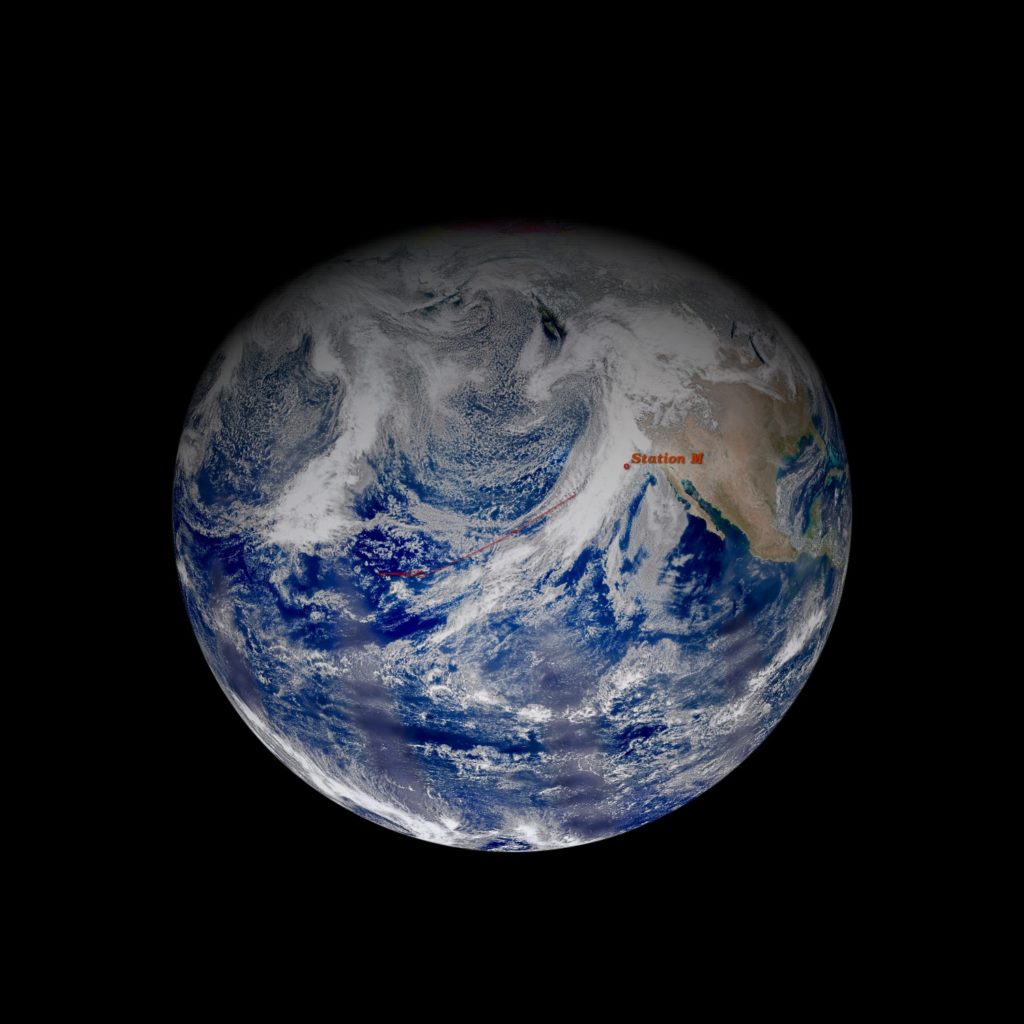

The Atmospheric Tomography, or ATom, mission’s world survey of the atmosphere can’t fly the order of its locations in reverse.

Its flight plan begins with traveling from California to Alaska and the North Pole before flying south down the center of the Pacific Ocean by way of Hawaii to New Zealand. From New Zealand, they cross east to Chile before ascending north up the Atlantic to Greenland.

It’s this southernmost crossing from Christchurch, New Zealand, to Punta Arenas, Chile, that’s a one-way street.

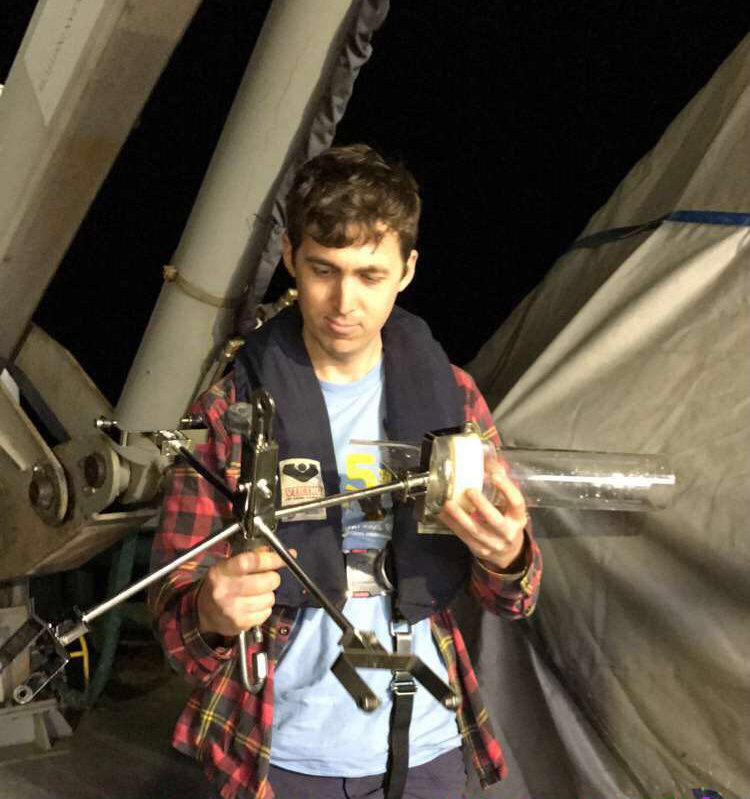

“The plane can’t make it from Punta Arenas to New Zealand because the winds are too strong,” said Róisín Commane, an atmospheric scientist at Harvard University who is part of the ATom mission.

The winds that travel from west to east above the Southern Ocean around Antarctica are among the strongest in the world. With few land masses to slow them down, they blow unimpeded.

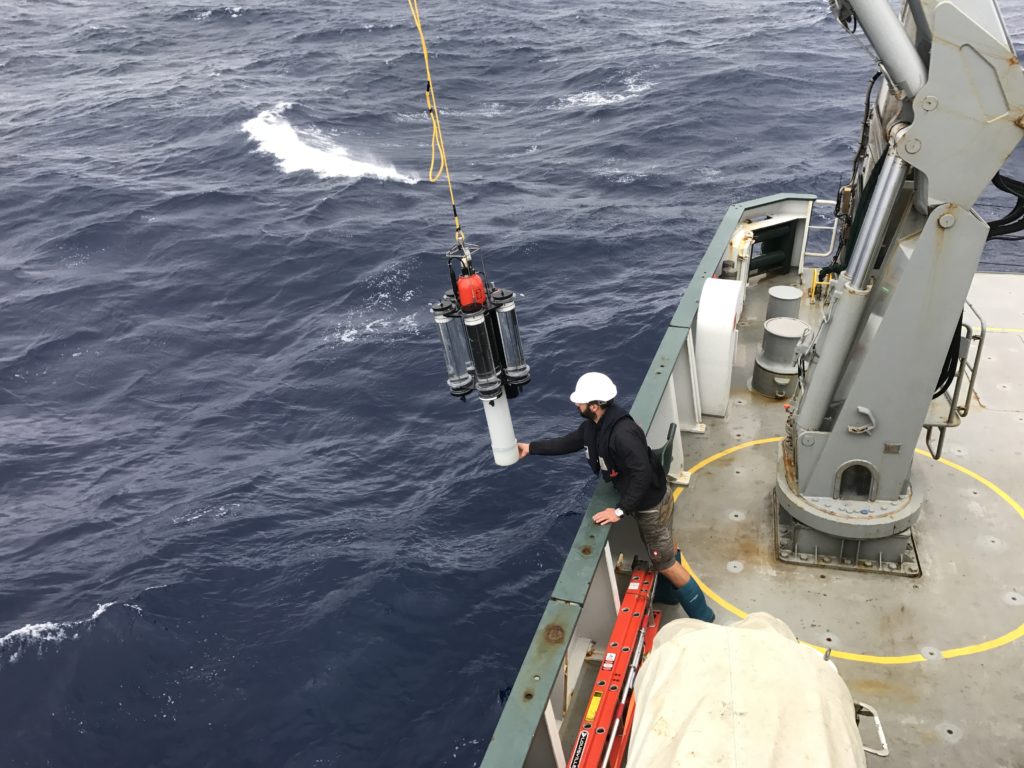

Those strong winds led to complications for the ATom team as they were preparing for their Feb. 10 flight from Christchurch to Punta Arenas. In a small hotel conference room around a cell phone and computers sharing a screen from weather forecasters back at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Steve Wofsy, ATom’s project scientist, peered at a circular weather system at the end of their flight path. The system created an eddy in the prevailing west-east wind that coincided with their arrival in Punta Arenas. The concern around the table was that strong winds would be blowing perpendicular to the runway when the plane was trying to land, potentially pushing it sideways.

The DC-8 can handle this kind of crosswind up to about 25 knots, or 28 miles per hour. Above that, for safety the pilots would have to divert to a back-up landing site. The closest in Chile was in the range of the same weather system—and likely to have the same crosswinds. The other was in Argentina two hours away, which would require fuel reserves that would take away from the number of profiles of the atmosphere they could do on the crossing, one of the main reasons for this mission. It would also require a second flight to get the team back to Punta Arenas the day after the system passed.

It was a disruption that Wofsy didn’t want to take on after an already difficult 10-hour flight with an 8-hour time change. From their experience on ATom’s first deployment in 2016, they knew from experience that the jet lag on this leg of the trip was brutal.

After three mornings watching the updated forecasts and NASA ground personnel talking with local weather forecasters in Punta Arenas, the morning of their scheduled departure from New Zealand arrived. The forecast hadn’t changed much. There was a 20-25 percent chance that the winds would be too strong and the plane would have to divert, said Wofsy. After a last early morning meeting with the pilots and forecasters, they made the decision to scrub the flight and wait a day for the storm to pass.

By the next day the system had indeed moved on, and the runway in Chile was safe for landing. The ATom team departed after their extra day in Christchurch and with. an adjusted schedule that would give them one less day in Punta Arenas. But on a mission dependent on good weather, that’s the way the wind blows.