Hi all, you may remember me, Linette Boisvert, from previous blogs such as “Team Sea Ice or Team Land Ice?” and “Sick Sacks for Science,” where I gave a visiting scientist’s perspective on test flights for NASA’s Operation IceBridge Arctic Spring campaign. Well now I am back, but this time as the deputy project scientist for IceBridge. Yes, a lot has changed since my last blog.

Beginning the second week of October, I will be flying down to Punta Arenas, Chile, (basically the other end of the Earth!) on NASA’s DC-8 flying laboratory to help lead IceBridge’s Antarctic Fall campaign. As I have never been to Chile, seen Antarctic sea ice in person (this is kind of a big deal), or flown on the DC-8 or met the crew, I took a short trip to NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center located in the California desert town of Palmdale, where the DC-8 is based.

Once on center, I entered the massive hangar that houses multiple planes. This hangar was originally used to make B-52 bombers before it was acquired by NASA, and it is so massive that scenes from Pirates of the Caribbean were even filmed inside. (They had to bring in a very large pool.) But there it was, dwarfed by the large hangar: the DC-8. It will be my mobile “office” for the month of October, when we’ll do 12-hour flights from Punta Arenas, flying over the Antarctic sea ice and land ice and back again, taking measurements with lasers and radars. We do this every fall to monitor changes in the ice thickness.

Now, this plane is a whole different beast than the NASA P-3 that I am accustomed to. It can seat up to 44 people with instruments aboard, compared to the 20 people that the P-3 can carry. The DC-8 has first class seats that recline and also has THREE bathrooms, and they’re like commercial airline bathrooms and not like composting toilets—what luxury! But when I first stepped onto the plane, it was basically empty. Seats were scattered around, there were containers about. I thought: “Are we really going to be able to fly this in a few weeks?” You see, I had arrived at the beginning of what we can “install,” and clearly there was a lot of work to be done. So naturally I was ready to lend a hand in any way that I could.

My first task was to help Mission Scientist John Sonntag, “The man, the myth, the legend” (as he is often called), with a ground Global Positioning System (GPS) survey. This basically means we would spend hours outside in the desert heat and sun, looking a little silly, pushing a cart around with a GPS antennae attached. We would be doing this at multiple specific locations around the parking lot and the runway. Now you might be wondering why we are torturing ourselves. For science and the mission of course! We need highly accurate GPS locations of easy-to-spot points from digital imagery so that we can geolocate our digital imagery and calibrate our camera during the test flights. Our instruments need to be calibrated so we can know the exact locations of our data when we fly and take measurements.

So now that is cleared up you might be wondering, okay, why do you have this antennae jerry rigged to this cart? I learned that GPS antennas are finicky, and the antennae need to be pointed unobstructed to the sky to receive signals from the multiple satellites orbiting overhead. Thus, it cannot be blocked by anything from above, such as your head, lampposts, or trees because if any contact with the satellites is lost during the survey, it would have to be done all over again. The other option would be to carry this around with the antennae above your head the whole time, so having the choice, I think I will take the cart.

Well, it turns out we had to eventually abandon the cart, because some of our survey points were located in the desert brush, and our little cart was not made for off-roading. We tried. As we were trudging through the desert carrying the antennae above our heads, John told me all about rattlesnakes and what I should be on the lookout for. Great, with my luck we would come upon one. But alas, we didn’t run into any of our reptilian friends and were able to complete our surveys, albeit a bit parched, sunburnt, and sweaty.

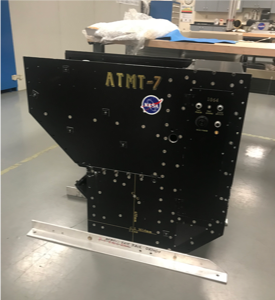

Now while we were surveying in the desert, the Airborne Topographic Mapper (ATM) team, the “Dream Team,” as I call them, were hard at work in the hangar installing their GPS ground station ATM T-6 and T-7 lasers

onto the belly of the DC-8, as well as their racks, which hold all of their computers and servers on the interior. They worked diligently for four long days, and at the end of the fourth day, they were finally ready to install ATM T-7. This baby weighs about 200 lbs and to me looked to be too big to fit into the door in the belly of the plane, so I knew I had to witness this!

The laser was wheeled out to the plane, where it was then put onto a forklift, lifted up, and gingerly slid into the belly of the plane. It was a tight fit, and I was nervous to say the least, but it all worked out in the end. Phew! Next week the radar instrument teams will begin their install.

The ATM T-7 installation into the belly of the DC-8. Credits: Linette Boisvert

Before I left on my last day, I took a few quiet moments in the DC-8. Compared to when I arrived, the plane looked almost put together. I was in shock with how quickly and seamlessly the crew and the ATM team worked together. The seats were nearly all set up, and the ATM and navigation racks were installed. I felt a sigh of relief knowing that I would be working with a group of scientists and engineers who worked hard, and that no matter what unexpected issues or problems arose on this upcoming campaign, we would all be able to work together to fix the problem and continue to collect valuable science data of the Antarctic ice. Lets just say I couldn’t be more proud and honored to be a part of this IceBridge team.

I also want to note that I am also very content to not be partaking in the DC-8 test flights next week over the desert, where they can be very turbulent, because I am not looking forward to having to test out any more “sick sacks.”