by Samson Reiny / ANGELES CITY, PAMPANGA, PHILIPPINES /

There’s a lot to get excited about on an airborne science campaign like the Cloud, Aerosol, and Monsoon Processes Philippines Experiment (CAMP2Ex). From watching data stream in from instruments observing fire smoke that had never been sampled in detail, to stunning imagery of the skies captured during flight, there are more highs to be had than can be counted.

But, for me, the pinnacle of the campaign is the people. CAMP2Ex involves collaborators from government agencies and universities across the United States, the Philippines, Japan, and Europe all working together to better understand fundamental processes between clouds and aerosols that drive climate and weather across the globe. And, perhaps most reassuringly for our collective future, the next generation of scientists is also very actively involved in both the planning and execution of the campaign.

Students and early-career collaborators from the Manila Observatory, a key partner in CAMP2Ex, share what they’ve been up to and where they may go from here.

How are you involved in CAMP2Ex? What have you learned from this experience so far?

We’re working the forecasts for this airborne campaign, which is a first for us.

As a student from the climate systems group, we’ve mainly worked with climate models. Modeling mostly confines us to working on our desks. Here at CAMP2Ex, our forecasting job goes beyond the books. It’s putting what we study to task.

How does your area of academic interest intersect with the objectives of the campaign?

I’m working on my master’s in atmospheric science at Ateneo [de Manila University], and for my thesis with the Manila Observatory I’m looking at the effects that urban cities have on the vertical mixing of aerosols, heat, and moisture over what we call the boundary layer. Manila used to be a mix of rural and urban areas, but now that we’ve altered that landscape, I’m looking into how those changes have affected our local weather.

A key area of interest for me in particular is urban pollution. There’s an instrument called a lidar. We have one ground lidar at the Manila Observatory and another on the NASA P-3B. So what I’m trying to get from this campaign are the comparisons of the measurements, specifically over Manila, since the plane can give you spatial variability as it passes other surfaces such as coastal or rural areas. I’m hoping to see the difference of that vertical mixing, not just the air flow but also the heat and moisture, which drives the atmospheric instability and leads to thunderstorms.

What is the most valuable part of this experience so far?

We are very thankful to our mentors Dr. Gemma Narisma, Dr. James Simpas, and Dr. Obie Cambaliza for bringing us to CAMP2Ex and trusting us that we can handle this kind of high-pressure environment. Secondly, I’m thankful for the openness of the scientists, specifically Bob Holz and Ralph Kuehn from University of Wisconsin for letting me do the initial analysis for the convective boundary layer height for the HSRL [High Spectral Resolution Lidar]. I’m also thankful to Jeff [Reid] for how he’s pushed us to be assertive and to be a part of the flight planning and mission management.

What are your goals following the campaign?

I’m really hoping to get a science visit to one of the institutions and really see their work environment and hopefully bring that experience back to the Manila Observatory, because seeing how fast they work after every flight and how they go about their initial analysis, that’s something we can bring back to the Philippines and the research that we do.

Kevin Henson

How are you involved in CAMP2Ex? What have you learned from this experience so far?

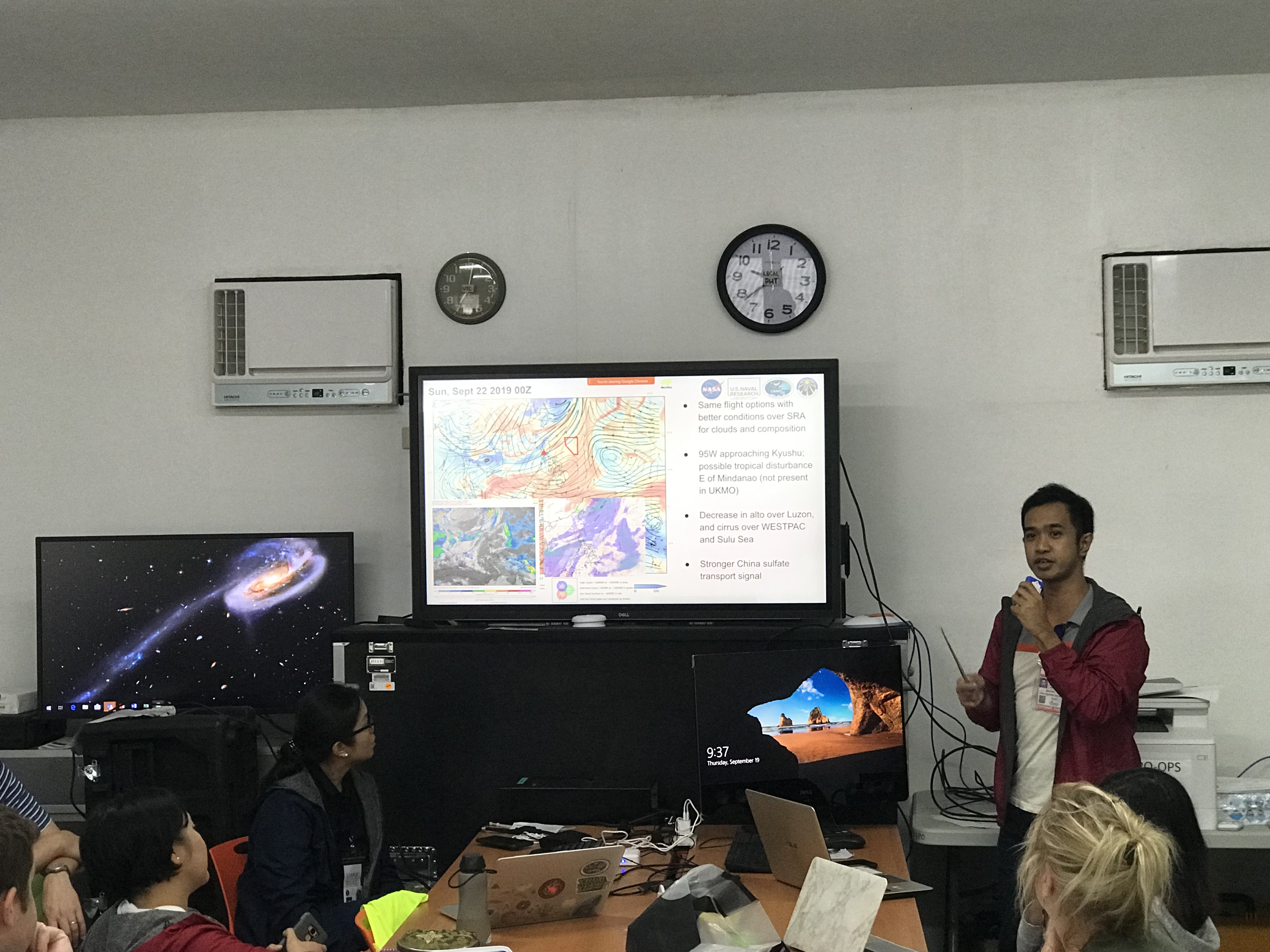

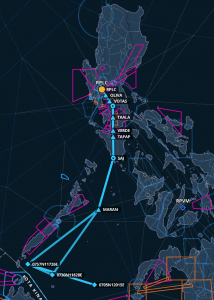

At the Manila Observatory, we don’t do a lot of weather forecasting. This is the first time that we’re heavily involved in it, especially for an airborne campaign. So that’s primarily my role: being a part of the forecasting group and planning where the flights will go and locating where the best areas to do the science are.

On the side, I’m also doing research on the Manila plume, which is essentially the pollution coming from Manila. I’m trying to find out where it’s being transported, especially in relation to the local terrain and meteorology.

How does your area of academic interest intersect with the objectives of the campaign?

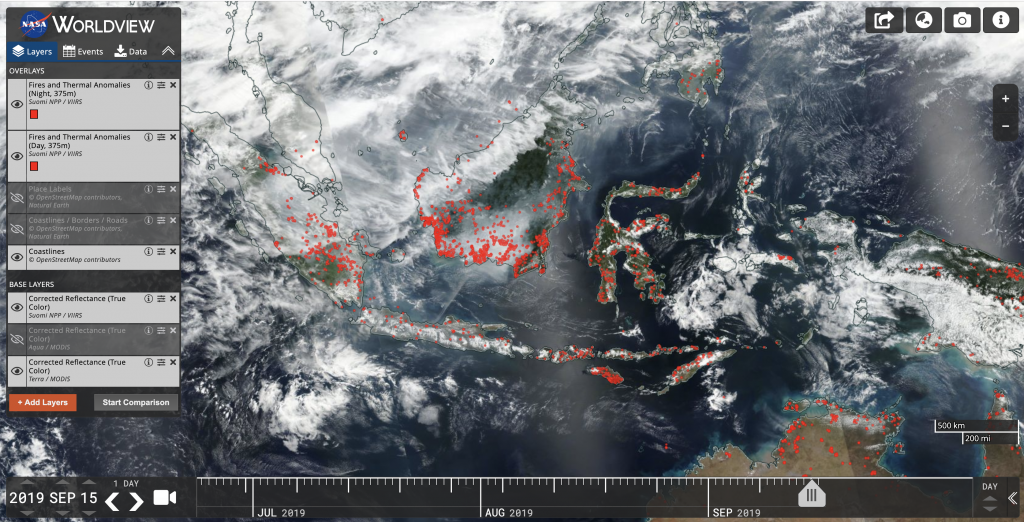

My main research area for CAMP2Ex is modeling pollution transport, both from local sources, mainly metro Manila, and what’s coming into the Philippines, as we saw a few days ago with the smoke from Indonesia. So I’ve mostly been modeling these things, but to see it actually firsthand through airplane observations has been eye-opening.

What is the most valuable part of this experience so far?

This experience is a dream come true for me. I’ve always been a NASA fan since I was younger, and I have always been inspired to do science because of all the things I’ve seen NASA do and accomplish. Coming into this campaign, I’ve only just read the papers of the different scientists, but now I’m having actual face-to-face conversations with them. Understanding their thought processes has been very enlightening. I get to see how they develop their science questions and hypotheses and how they analyze data. That’s really one of the biggest takeaways for me—learning from these seasoned scientists.

What are your goals following the campaign?

In the long term, I’m interested in looking at aerosol and cloud interactions. But before you can even go there you really have to know where the pollution is going, which means making sure your models are getting the transport right. That’s the baseline that you work with before you proceed with any further investigation, and that’s part of what we’re doing here at CAMP2Ex.

Angela Magnaye

How are you involved in CAMP2Ex? What have you learned from this experience so far?

My role is forecasting, and I’ve also been doing some model validations, which is one of my interests because I do climate modeling at the Manila Observatory-Regional Climate Systems Laboratory. I’m also interested in land-sea temperature contrast as part of my research for CAMP2Ex.

This is a very different experience for me. The only time I have done anything like this was in 2017 for the pre-PISTON [Propagation of Intra-Seasonal Tropical Oscillations] campaign, which was not an airborne campaign but a research vessel campaign in the northwest Luzon coast.

How does your area of academic interest intersect with the objectives of the campaign?

I’ve been studying a lot of air-sea interactions with climate models for my master’s degree in atmospheric science in the Ateneo, and I’m here to help with the validation of those models. With the data acquired from the Sally Ride and the NASA P-3, we’ll have more information on how the air and sea interact and affect convection, cloud formation, and precipitation, and that’s very important for the models, especially when we do long-term runs. That can help us a lot.

What is the most valuable part of this experience so far?

In the forecasting team, we are particularly grateful for Ed Fukada, lead forecaster of this campaign because of his decades of expertise in weather and typhoon forecasting. Also, for me, it’s the collaboration with international scientists. We don’t get this chance very often, and it’s very valuable for the students to be interacting with experts in the field. We get to consult with them to gain more insights into our own work, and at the same time, we also teach them more about our region, because the meteorology in the tropics is very different. So maybe our insights might help them with their analysis as well.

What are your goals following the campaign?

I want to pursue Ph.D. studies abroad and then come back to the Philippines. It’s important to get insights and expertise from scientists around the world and then hopefully bring that back here so that we can have more capacity building here I the Philippines and have more scientists in the Philippines as well.

Emilio Gozo

How are you involved in CAMP2Ex? What have you learned from this experience so far?

Right now, I’m part of the microphysics team of the Manila Observatory, and we’re trying to investigate why rainfall in the models is usually overestimated. Somehow, cloud particles in the tropics, especially in the Philippines, are different from those in the mid-latitudes. A hypothesis for the difference is the pollution coming from China and Borneo. Pollution acts as seeds for clouds and it affects rainfall amounts. So we’re trying to see from this mission how the structure and content of clouds are different in this region.

How does your area of academic interest intersect with the objectives of the campaign?

I just finished my master’s degree in atmospheric science. My research now is centered on the effect that changes in urban land cover have on the amount of rainfall. For this campaign it’s a little different, as we’re looking at how cloud structures change, so now we’re incorporating pollution as it relates to the aerosol content in clouds.

What is the most valuable part of this experience so far?

So far, everything is pretty new to me, from the on-the-spot weather forecasting to talking in front of lots of scientists. I’m used to research meetings with just a few people. Now you’re trying to convince a lot of scientists where to fly and when or whether or not we should fly at all on a given day. Also, all of the scientists are very open and easy to talk to if you have questions. It’s a productive environment for research.

What are your goals following the campaign?

From this campaign, there will be lots of data to look at, so I’ll probably analyze the data and write science papers. It’s very inspiring to see all the scientists here working together, so now I’m motivated.