The International Space Station Program Science Office would like to dedicate this entry of A Lab Aloft to the life and work of astronaut Sally Ride, who passed away July 23, 2012. In today’s A Lab Aloft, guest blogger Cindy Evans remembers working alongside Sally and the inspirational legacy she leaves behind.

I was just thinking about Sally Ride last week, while my family and I were on vacation in Russia. One afternoon we decided to visit the spectacular Monument to the Conquerors of Space in Moscow. The impressive park that surrounds a soaring rocket features statues of some of the Russian spaceflight pioneers, such as Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space. Reflecting on Valentina’s face quickly led to a family discussion of American space pioneers, including the first U.S. woman in space: Sally Ride.

Sally Ride was in the first group of astronauts to include women. Here she looks out of the space shuttle window to gaze at Earth from orbit. (Credit: NASA)

Of course, Sally is remembered for lots of things in addition to her first spaceflight mission. She was also a scientist and a champion of teachers, students and parents around the world because of her passion for education. It was this love of learning and the desire to share it with others that led to me getting to know Sally.

I met Sally in 1995 when she invited me to be part of her team to plan her space shuttle educational payload: KidSat. This was the pilot program for what would evolve into today’s EarthKAM, one of the most prolific education investigations on the International Space Station.

Sally’s concept for KidSat was simple: put an Earth-viewing camera on the space shuttle and let middle school kids take photos. Their target could be their own town, a place they are studying in history class, the Amazon rainforest, or the location of an event in the daily news. By letting kids control a camera from space, Sally knew they would be inspired as they learned.

Teachers used KidSat as a launching point to cover lessons on a wide variety of topics. They highlighted the basics of spaceflight, including gravity and orbits. Students applied KidSat to math and science, too. They learned the importance of precise calculations to make sure they could capture their targets. In viewing the final images, students covered Earth science and geography and honed their communications skills by describing their observations in writing. As a team-oriented task, KidSat reinforced the importance of working together to achieve greater successes.

When I was working with Sally in the mid-1990s, we were simply trying to see if KidSat could work. The first mission in 1996 was tested by teachers and students from only three middle schools: a rural school in Humbolt, Calif.; an inner-city school in San Diego, Calif.; and a magnet academy in Charleston, S.C. The small educational team included teachers from these schools and a few more.

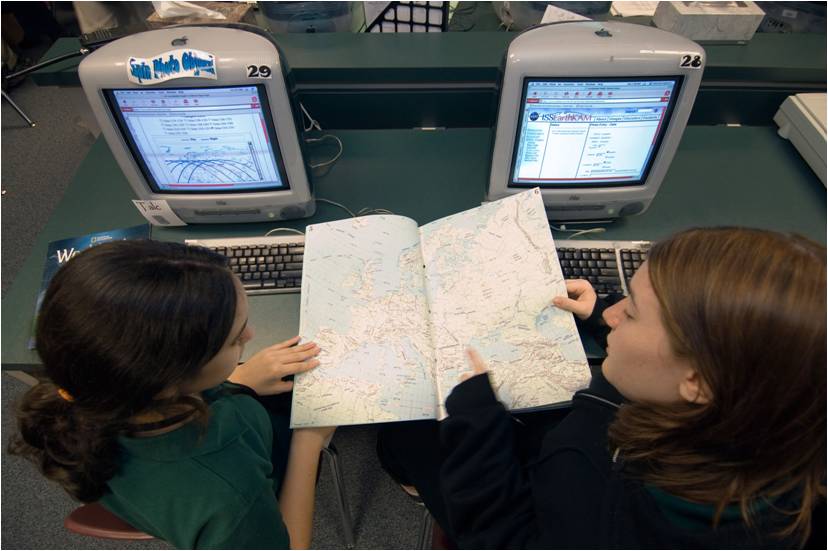

Westbrook seventh-graders Emily and Jessica use a map and the Internet to determine the latitude and longitude of their next picture. (Credit: NASA)

Sally assembled a diverse team for KidSat, including education specialists from NASA’s education program, flight controllers from NASA’s Johnson Space Center mission operations, college students at the University of California, San Diego, database experts from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, and a couple of interdisciplinary Earth scientists like myself to guide the science curriculum development with the small cadre of middle school teachers.

Every step of the way, Sally leaned on those teachers to make KidSat work. The teachers wrote the classroom activities and provided feedback on the spaceflight stuff (orbital dynamics for 6th graders—really?). They thought through the implications of conducting a mission in the classroom during the middle of the school year, which would include four days straight and midnight operations! The team also forecasted potential failure scenarios from a classroom perspective, such as: What if my dyslexic students transpose numbers? What if we can’t get Internet? What if it is cloudy?

This truly collaborative and interdisciplinary partnership that provided opportunities for KidSat continues today with space station’s EarthKAM. The inspiration and lessons spill over from science classes into other areas, such as art, math, English, and even gym!

Of course, both of Sally Ride’s Earth observation investigations were remarkably successful. KidSat grew during the first 3 flights of the program from 3 to 17 to 52 schools! Hundreds of schools have participated since that time, involving tens of thousands of students. Today, EarthKAM continues to inspire where KidSat left off. Pulling in thousands of participants with each operational opportunity, EarthKAM has reached more than 190,000 students to date.

My reflection about Sally leads to the core of what she inspired and championed—innovative learning for middle school kids, and a celebration of our natural curiosity about Earth and the Solar System. Through her legacy, she will continue to inspire for generations to come and I am honored to have been part of her team.

Cynthia Evans, Ph.D., is Associate International Space Station Program Scientist for Earth Observations and Deputy Manager for Astromaterials Acquisition and Curation Office. Evans holds degrees in Earth Science and Geology, and has been active in Earth Observations from the space shuttle, the NASA-Mir Program and the space station. She has participated as a science team member in several Desert RATS analog missions, and manages the GeoLab workstation—a glovebox-based test article integrated into the Deep Space Habitat testbed. As a volunteer, Evans also taught several EarthKAM classes at local middle schools.