In today’s A Lab Aloft, Charlie Quincy, research advisor to the International Space Station Ground Processing and Research director at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, continues to share the growing potential of plants in space and the new plant habitat that will help guide researchers.

As astronauts continue to move away from Earth, our ties back to our planet are going to be strained. We won’t have the capability to jump into a return capsule and be back to Earth in 90 minutes.

To move further away from Earth, we have to continue to develop more autonomous systems in our spacecraft that supply our fundamental needs for oxygen production and carbon dioxide (CO2) removal, clean water and food. The genetic coding in plants to perform these functions has been refined and improved for the past 3-4 billion years as plants have continually evolved on Earth. So the code is pretty good. As long as we can provide biological organisms like plants or algae with the nutrients and support systems they need, they will pretty much know what to do. What they will do is clean water, change CO2 into oxygen and generate food. From a life support system, that’s kind of what you want to happen.

There are some interesting things about plants that we’ll have to deal with in space. For instance, we don’t have bumblebees in orbit, so who does the pollination? Who goes from flower to flower? We’ve actually had astronauts using cotton swabs to move pollen from one flower to another, in particular when we were growing strawberries a few years back. As we get more and more into it, we need to figure out how to do this without using the crew, since it would not be efficient to have them pollinating a field with cotton swabs.

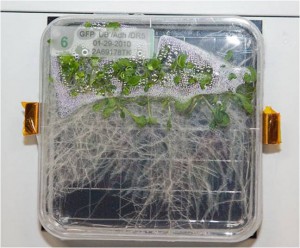

View of willow trees in an Advanced Biological Research System (ABRS) incubator for the Advanced Plant Experiments on Orbit – Cambium (APEX-Cambium) experiment aboard the International Space Station during Expedition 21. (NASA)

We have quite a number of things going on and coming to fruition on the International Space Station. We currently have a small habitat called the Advanced Biological Research System (ABRS) in orbit performing fundamental studies of plant growth in the microgravity environment. It has two independent chambers that are tightly controlled and have LED lights. We can manage moisture delivery, CO2 and trace gases inside those chambers and do some real hard science investigations. The Russian segment has a habitat, too, called the Lada greenhouse.

The Advanced Plant Habitat (APH) is a similar chamber under development, but that one will be larger. The APH will enable us to use larger plants and different species, all of which will be tightly controlled during growth investigations.

Another really exciting new system launching to the space station probably around the middle of next year is the Vegetable Production System (Veggie). It will begin bridging the gap between a pure science facility and a food production system. We are in the ground testing phase of the flight unit to assure it is safe for operation aboard the station with the help of the facility’s builder, Orbital Technologies Corporation of Madison, Wis. Orbitec. They also will manufacture the APH.

The beauty of the Veggie unit is that it’s really just a light canopy with a fan and a watering mat for growing plants, using the cabin atmosphere aboard the space station. The crew will have an opportunity to farm about two and a half square feet, which is a pretty good sized growing area. This system also has great potential as a platform for educational programs at the high school level, where students could grow the same plants in similar systems in their classrooms.

The Veggie greenhouse will fit into an EXPRESS Rack on the International Space Station for use with plant investigations in orbit. (NASA)

We’re going to start growing lettuce plants in Veggie next year as a test run, because lettuce is well suited for this initial testing. Lettuce is a good first crop selection because it is a rapid growing plant, with a high edible content, and generally has a small micro flora content. We will be using specially designed seed pillows to contain the below ground portion of the lettuce plant containing the roots, rooting media, and moisture delivery system. The plants will sprout and grow up through those pillows. Ultimately scientists will be able to grow larger plants like dwarf tomatoes or peppers.

We are continuing to do the testing associated with making sure the food grown in the closed environment of the space station is safe to eat for the crew. We hope that within a short period we will be able to augment the astronauts’ diets with herbs and spices and maybe onions, peppers or tomatoes, something to give the crunch factor. Ultimately, we hope to move to even larger chambers to begin producing more of the staple crops, such as potatoes or beans.

All of these new plant systems should be up and running in the very near future. Veggie should be aboard station next year, and by the middle of 2015 we expect to deploy the APH, completing the suite of plant facilities in orbit.

When talking about life-support systems for spaceflight, there’s obviously a more complicated viewpoint that says the systems that connect all that together are pretty elaborate and cumbersome. There are reservoirs, hoppers and a vast array of other things that have to be in place to operate a bioregenerative system, which makes them big and, in some cases, energy intensive. On short-duration missions we would probably do better packing a picnic lunch and taking only the support systems we need. The further we are away from Earth, and the longer it takes us to get back, however, drives systems planning in the regenerative direction. What we’re doing is laying the groundwork that will enable those kinds of decisions to be made for long-duration exploration.

NASA astronaut Mike Fossum, Expedition 28 flight engineer, inspects a new growth experiment on the BIO-5 Rasteniya-2 (Plants-2) payload with its Lada-01 greenhouse in the Zvezda service module of the International Space Station. (NASA)

There’s a more near-term thing that we’re also looking at, which is the therapeutic aspects of growing plants. People have been exercising their “green thumbs” for this reason for years. They plant their little gardens, and the aromas of plants have a very positive impact on the way these people feel about things. The psychological effects of keeping plants are still somewhat unknown, and we’re hoping to get better insight into that. These effects include the nurturing aspects of watching something grow and caring for it. During spaceflight, far from Earth or on a long-duration mission, a totally sterile environment may not be what is desired. While you can’t have a pet dog or cat to make your living space a little more homey, perhaps you could have a pet plant to care for, as it provides oxygen and sustenance.

Charlie Quincy has been the Space Biology project manager at Kennedy Space Center for the past 13 years. His efforts include both flight and ground research aimed at expanding the current science knowledge base, solving issues associated with long-duration spaceflight and distributing knowledge to Earth applications. He is a registered professional engineer and has a master’s degree in Space Technologies.