In today’s A Lab Aloft, Dr. Larry DeLucas, a primary investigator for International Space Station studies on protein crystal growth in microgravity, explains the importance of such investigations and how they can lead to human health benefits.

We have many proteins in our body, but nobody knows just how many. Consider that the human genome project is more than 20,000 protein-coding genes, and many of these genes or portions of those genes combine with others to create new proteins. The human body could have anywhere from a half million to as many as two million proteins—we’re not sure. What we do know, is that these proteins control aspects of human health and understanding them is an important beginning step in developing and improving treatments for diseases and much more.

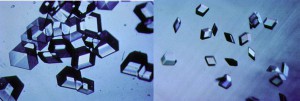

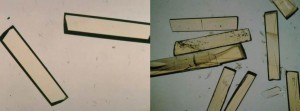

A protein crystal is a specific protein repeated over and over a hundred thousand times or more in a perfect lattice. Like a row of bricks on a wall, but in three dimensions. The more perfectly aligned that row of bricks or the protein in the crystal, the more we can learn of its nature. Today there are more than 50,000 proteins that have been crystallized and the structures of the three-dimensional proteins comprising these crystals have been determined. Unfortunately many important proteins that we would like to know the three-dimensional structures for have either resisted crystallization or have yielded crystals of such inferior quality that their structures cannot be determined.

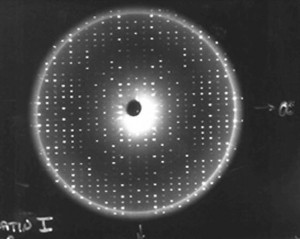

Once we have a usable protein crystal—one that is large and perfect enough to examine—the primary technique we use to determine the protein molecular structures is x-ray crystallography. When we expose protein crystals to an x-ray beam, we get what’s called constructive interference. This is where the diffracted x-rays coming from the electrons around each atom and each protein come together, providing a more intense diffraction spot. We collect hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions of diffraction spots for a protein. The more perfectly ordered the individual protein molecules are within the crystals, the more intense these spots. The higher signal to noise ratio in these strong spots creates an improved resolution of the structure, allowing us to map the crystal in detail.

Using computers, we take those diffraction spots and mathematically determine the structure of where every atom is in the protein. For example, in most protein structures we can’t even see the hydrogen atoms. We guess where they are because we know the length of a hydrogen bond. So if we see a nitrogen atom from an amino acid that we know has a hydrogen linked to it, and then at a hydrogen-bonding distance away we see an oxygen atom, then we can make an educated guess that the hydrogen is pointed towards that oxygen atom, so we position it there.

While we can grow high-resolution crystals both in space and on the ground, those grown in space are often more perfectly formed. That’s the main advantage and reason we’ve gone to space for these studies. In many cases where we could not see hydrogen crystals on the ground, we then flew that protein crystal in space and let them grow in microgravity. Because of the resulting improved order of the molecules laying down in the crystal lattice, we were able to actually see the hydrogen atoms. Usually to see the hydrogen atoms, you are talking about getting down to a resolution of one angstrom, which is not easy to do—it would take 10 million angstroms to equal one millimeter!

We also can look at bacteria and virus protein structures to identify how to target those proteins with drugs. Having this information is very important to pharmaceutical companies and universities. That structure provides a road map that is critical for the understanding of the life cycle of the bacteria or virus.

We’ve only done a fraction of the more important complex protein structures–I’m referring to membrane proteins and protein-protein complexes. Protein complexes are often composed of two, three or more proteins that interact together to form new macromolecular complexes that are often important in terms of disease and drug development. Membrane proteins are the targets for about 55 percent of the drugs on the market today. Scientists have determined the three-dimensional structures for less than 300 membrane protein structures thus far. However, there remain thousands more for which the structures would help scientists understand their important roles in chronic and infectious diseases.

When we see a specific region in a protein and we know exactly where every atom is, chemists can design drugs that will interact in those regions. We can take some of the drugs they design that work, but maybe not as well as we would like. We then grow new crystals of the protein with the drug attached to the protein to see exactly how it’s bound to the protein. That lets other scientists—modelers—determine very clearly how the drug interacts with the protein, information that enables them to design new, more effective compounds. This whole process is called structure-based drug design.

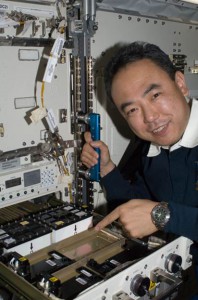

The International Space Station provides a unique environment where we can improve the quality of protein crystals. During the days of protein crystallization studies on the space shuttle, one of the most frustrating aspects of the microgravity experiments was the length of time it took to produce a usable crystal. This is actually part of why space-developed crystals are better—they grow much more slowly. On the shuttle you only had 10-12 days for a study, but aboard the space station you have as long as you need.

As an astronaut and scientist, I personally flew a record 14-day flight in 1992 where we studied 31 proteins. I was looking at results and planning to set up new experiments, changing the chemical conditions to optimize the crystallization. The rule for my sample selection was that the proteins had to nucleate—that means to begin to grow a crystal—and grow to full size in three days. Once I got up there, however, by the third day nothing had nucleated. I was worried, but then on the fourth day I could see little sparkles where crystals had started to grow in about half of the proteins. By mission end I was really only able to optimize the crystal growth for six of the proteins. How much longer it takes a crystal to nucleate and grow to full size was a dramatic discovery.

With constant access to a microgravity lab, such as the space station, I am confident that we can improve the quality of any crystal. With protein crystals it is important to note that just because we get a better structure with higher resolution, it doesn’t at all mean it’s going to lead to a drug.

The ability to grow good crystals typically involves a great deal of preparation on the ground where we first express and purify and grow the initial crystals. But if space can give you higher resolution, there’s no drug discovery program that’s going to take a lower resolution option. From the time you determine that structure and chemists work with it, the typical time frame to develop a drug is 15 to 20 years and the cost is around a billion dollars. Identifying the structure of the protein crystal is only the first step. Many times even with the structure a project goes nowhere because the drugs they develop end up being unusable. There are so many aspects to drug discovery beyond the opening act of structure mapping.

If crystals and the structure of a target protein are available, pharmaceutical and biotech companies certainly prefer to use that structure to help guide the drug discovery. After the first 18 months they’ve developed the drug candidates, they may not need to use the crystal structure again for say 10 years. During that time they are doing clinical trials and pharmacology. The majority of the money it takes to get a drug approved by the FDA is after the initial phase. If you break down what they say is about a billion dollars to develop a drug, the portion needed to get the structure up front will range from half to two million dollars—a small fraction of the whole process.

For the upcoming Comprehensive Evaluation of Microgravity Protein Crystallization investigation we focused on two things. First, we selected proteins that are of high value based on their biology. Having this information of their structure can lead to new information about structural biology—how proteins work in our body. The other major requirement for the candidates for selection was that the proteins had to have already been crystallized on Earth, but the Earth-grown crystals were not of good quality.

We are flying 100 proteins to the space station on SpaceX-3, currently scheduled for March 2014. Twenty-two of these are membrane proteins, 12 are protein complexes, and the rest are aqueous proteins important for the biology we will learn from their structures. The associated disease was the last thing we considered, as we were looking at the bigger picture of the biology. That being said, for the upcoming proteins flying you can almost name a disease: cystic fibrosis, diabetes; several types of cancer, including colon and prostate; many antibacterial proteins; antifungals; etc. There are even some involved with understanding how cells produce energy, which I suspect could lead to a better understanding of molecular energy.

Not long ago a Nobel Prize was awarded for the mapping of the ribosomes complex protein structure. This key cellular structure will also fly for study aboard the space station, because the resolution was not all that great using the ground-grown crystals. We now have the chance to learn more about how the ribosomes actually makes proteins and clarify the whole process. This is just one of the exciting projects flying in relation to protein crystal growth.

This space station experimentation is a double blind study. This means that all the experiment chambers are bar coded for anonymity. We also will have exact controls done with the exact same batch of proteins prepared at the same time. The crystals will grow for the same length of time, as they are activated simultaneously in space and on the ground. When the samples come down, we will perform the entire analysis not knowing which are samples grown in space versus Earth. Only one engineer will have the key to the bar codes. When we’re completely done with the analysis, then he will let us know which were from space or ground. This will allow our study to provide definitive data on the value of space crystallization.

We also wanted to ensure that our analysis looked at a sufficient number of samples, statistically speaking, to provide conclusive data. How many data sets we collect per crystal sample will depend on the quality of that crystal. Statistically the study will be relevant in terms of how many proteins we fly, as well as how many crystals we evaluate from space and ground to make the comparison.

The microgravity environment is so beneficial because it allows the crystals to grow freely. Without the gravitational force obscuring the crystal molecules, as seen on Earth, the crystals can reveal their full form. We are giving all of these protein crystals the chance to grow to their full size in a quiescent environment. This is a very important investigation, not only because of the high number of proteins we are flying, but the statistical way we will evaluate them. Based on the results of the study, we will know if PCG in space is worth continuing.

Once the crystals come back to Earth, it will take at least one year to complete the full analysis. However, we will likely know that we’ve got some exciting results within the first three months. To publish something, it will be at least a year to complete the analysis, as we will have about 1,400 data sets to analyze. These results will determine the future of microgravity protein crystallization.

Larry DeLucas, O.D., Ph.D. is Director for the Center of Structural Biology and a professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Dr. DeLucas flew as a payload specialist on the United States Microgravity Laboratory-1 flight, Mission STS-50, in June1992. His work is currently funded through NASA and the National Institutes of Health.

Oh my God, oh my God. The sequence at 1.47 reveals an image we also find in Cambodgia at the temple Angkor Wat I think. It is just that the temple was built a long, long time ago. Congrats!