The following is aninterview with International Space Station Associate Program Scientist TaraRuttley and Southwest Research Institute Associate Vice President for Researchand Development Alan Stern as they discuss the benefits and differences betweenthe space station and suborbital research platforms.

A Lab Aloft’s JessicaNimon: Alan and Tara, thank you forjoining me. Today we are talking about the topic of microgravity researchplatforms. I sometimes hear people treat suborbital and orbital laboratoryoptions as synonymous. These options, however, offer distinctly differentbenefits. Alan, can you tell me what makes suborbital research unique?

Stern: Suborbitalis special for a number of reasons. First of all, it offers low cost and morefrequent spaceflight than we can currently achieve with orbital research. Italso provides the space station with a great training and proving ground. Sodespite its many amazing capabilities, space station is highly constrained interms of crew time, how much equipment you can get back and forth and room toplace investigations. Naturally, only the most important experiments can go upto station and they receive limited crew time. This is part of why it isimportant for the station to have a proving ground—like suborbital—where youcan test the equipment, the techniques and the science. This way selections forwhich experiments should go up to station can be made based on experience inresearch, not just theory.

My analogy for the relationship between the station andsuborbital research is a baseball one: the major leagues rely on the minors asa feeder system and I think this is a similar relationship between station (i.e.,the major leagues) and suborbital (i.e., the minors). Without the minorleagues, the majors would be crippled; they would not have the farm teams todevelop techniques and players. I think the station can use suborbital in thesame way and very cost effectively.

Ruttley: I agreewith Alan that suborbital research can help to pare out the tests thatinvestigators want to do. It could be a way for a scientist to get a goodhandle on a hypothesis prior to working with the space station. Once aninvestigator knows what might be seen in microgravity, a decision can be madeon the next step.

One of the advantages of working with the space station isthis ability for continuous testing. On the ground, scientists do oneexperiment, look at the results, and then repeat in a lab setting withcontrolled variables. The space station provides a researcher the ability toperform multiple trials to increase the data set, thereby offering longevitywith a sustainable presence in space.

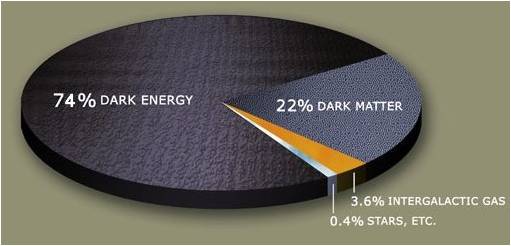

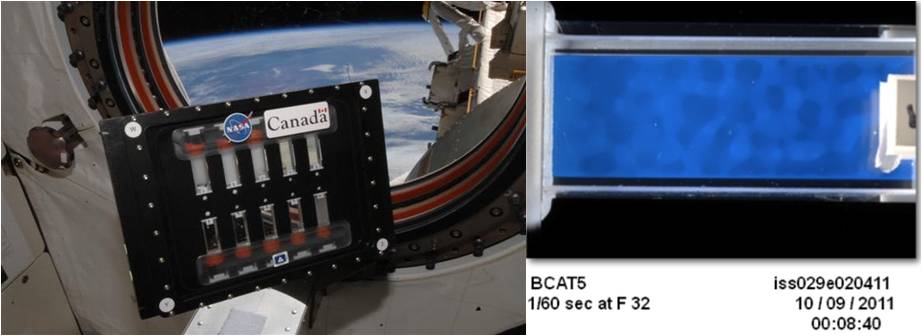

You have large opportunities for data and power, as well. Theseare huge resources for investigations like the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer or AMS.This study could not sustain itself without the space station’s power and data capabilities.Space station also provides a humanin the loop to help troubleshoot in real time and potentially move theinvestigation on to the next step.

The starboard truss of theInternational Space Station with the newly-installed Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer-2, or AMS,

visible at center left.

(NASA Image S134E007532)

Something else to consider is that the space station offersnot only the U.S. laboratory, but also access to our international partnerlabs. Each partner module has its own range of facilitiesfor investigators to potentially take advantage of. This includes externalmounting for studies seeking exposure to the space environment. It is appealingto researchers that we have this massive, interdisciplinary, resupplied andfully-outfitted research laboratory on orbit.

A Lab Aloft’s Jessica Nimon: Alan, you mentioned thatsuborbital research can feed into station investigations. I’m curious, doesthis ever occur in reverse? Have findings from station studies contributed to suborbitalresearch?

Stern: Not yet. I think that’s largely the outcomeof limitations with the current suborbital program at NASA. For one, NASA’scurrent suborbital program does not fly very often and it’s very expensive. Secondly,it’s primarily a Science Mission Directorate program and station does not do alot of planetary science, astrophysics or much Earth science—the mainstays ofthe Science Mission Directorate. These could be future areas, however, for thespace station to expand into.

But I also think the new commercially reusable suborbitalefforts are going to really change current paradigms and allow things to workin both directions. This is because the user community will vastly expand withdaily flights—instead of monthly flights—and lower costs will enable more trialand error experimentation like in a regular lab. The people interested incommercial suborbital are not necessarily looking at the same goals at the ScienceMission Directorate. They are looking instead at the things that fit betterwith station, in terms of the user base: microgravity, life sciences,technology tests.

Ruttley: There are a few NASA research announcements sponsoredby the Science Mission Directorate right now that encompass the use of thespace station. These are the ResearchOpportunities in Space and Earth Sciences, or ROSES, and the Stand Alone Missions of Opportunity Notice,or SALMON.

Stern: There are many places in the directorateportfolio that space station could assist with. Putting these things on thealready existing station platform makes sense; it would allow many kinds ofresearch to move forward faster. It is true, however, that while in many casesthis will work, some kinds of research just aren’t compatible with station. Forinstance, since station is a human space facility—which by nature has a lot ofoutgassing—it is too dirty for some kinds of external investigations.

A Lab Aloft’s JessicaNimon: Do you see a difference in interest or a preference from users towardseither platform?

Stern: Most of what I’ve heard is that there arelimited resources and too lengthy of a timeline for both station and suborbitalresearch. Fixing this for both arenas would be a home run hit. I think usersfind that suborbital is easier to work with, due to the faster timescales. Youcould spend 5 to 10 years in the past getting something to fly on shuttle, and2 or 3 years getting ready for a sounding rocket flight, but the commercialresearch and development cycle is usually less than a year—which is the verytimescale the new suborbital vehicles are comfortable with for arrangingflights.

If station can streamline its experiment manifesting andoperations, with COTS [commercial off-the-shelf] and commercial cargo goingback and forth, this may change. Now that we have great facilities aboard thespace station, I’d like to see the use of existing hardware to getinvestigations going more swiftly. Otherwise, the timescale is too big abarrier to most users. The space station needs to adapt the customer’s needs, Ithink, to increase its user base.

Ruttley: That has been the case in the past, Alan, butrecent National Lab efforts have done a lot to improve the timeline. TheNational Lab has been successful in securing several agreements with governmentagencies, commercial users, and universities for the use of the space station.National Lab Manager Marybeth Edeen recently wrote a blogon this topic of improving the timeline to flight. Payload developers usingexisting hardware have been able to fly to station in as little time as sixmonths . This is not the standard yet, but it is possible by pairingresearchers with existing certified payload developers to really accelerate theprocess.

Stern: I don’t think this is well known yet. Withthis changing for the positive, people need to know that the story haschanged—let’s get the word out faster.

Ruttley: That’s part of what we’re doing with thisblog and with our other media efforts, like the storieswe publish on our International Space Station Research and Technology Website.With the National Lab effort, over 50 percent of NASA’s assets are available tousers. Perhaps the new non-profitmanagement planned for National Lab will have additional ways to help getthe word out.

Stern: It’s good that the word is now starting toget out, but I think that more could be done to reach more users. PerhapsNational Lab can send representatives to host workshops at the meetings andconferences scientists attend, whether industrial or academic. Just to talk tothem and answer their questions on how to do business. Usually researchers arelooking for money, too, since universities don’t usually have their own for investigations.

Ruttley: I agree. I think the progress ofcommunication and the streamlined process will continue to improve over thenext few years. National Lab users do have to come up with their own researchfunding, but it’s been shown to be successful already. Just last year, the NationalInstitutes of Health, or NIH, gave three awardeesthe money to do their research on the station; NASA will integrate and launchthe investigations. While the National Lab and the Space Station PayloadsOffice are working on a streamlined process for launch and integration, researchfunding itself will always be the real issue for potential researchers.

A Lab Aloft’s Jessica Nimon: Where do you see the future of suborbitalresearch?

Stern: Right now there are five firms buildingreusable suborbital systems: Virgin Galactic, XCOR, Armadillo Aerospace, MastenSpace Systems and Blue Origin. Four carry people and payloads and one—i.e.,Masten—carries only payloads. While the legacy NASA suborbital program fliesinfrequently, these commercial companies plan a far more frequent flightschedule. Between several times a week and daily, so we’ll go from roughly twodozen flights per year to hundreds per year. This will be a huge change to users’access to space. It will be more affordable, too, maybe in the hundreds of thousandsof dollars.

Ruttley: The price of space station research is alsocoming down, because more and more experiment hardware can be reused. Companiessuch as BioServeor NanoRacks LLC offer excellent entrypoints for new experiments; you can do a lot on the space station in thehundreds of thousands range.

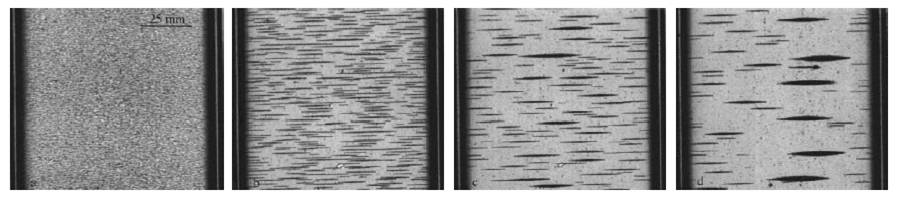

Dave Masten and Nadir Bagaveyev mounting the Amespayload rack onto the Xaero suborbital launch vehicle prior to a combined systems test.

(Credit: Doug Maclise)

A Lab Aloft’s Jessica Nimon: What is the operations duration for theseexperiments on suborbital flights?

Stern: It’s really short. The typical time they havein microgravity is three to four minutes, which is the same as the currentstandard suborbital option. You can make a well thought-out experiment run inthis timeframe, however, and then fly it again to get more data.

Keep in mind that there are multiple experimentsrunning at once on a given flight. Each seat can hold racks capable of housing asmany as 10 experiments—in just one seat! Virgin, for instance, plans to havesix seats available on six vehicles, which they plan to fly on a daily basis.Add to this the other companies similar numbers and over time and with enoughflights, suborbital has the potential to start returning many hours of research—ifall the seats are full. The difference is that it comes in little blips, ratherthan all at once.

Currently the U.S. flies only one suborbital soundingrocket mission every two weeks. So as all of the various suborbital companiesramp up to full operations, we have a huge magnification of capability. We willhave 10s of hours per week of available human research flight time, in additionto the onboard automated experiments. We are approximately four to five yearsaway from full operations.

Ruttley: This is a great way for short-durationexperiments to get microgravity time, especially as demand for the space station’slong-duration capabilities grows. The suborbital option can potentially free upthe station platform for investigations that need to run for longer than threeminutes in a given flight. The two options really could work in concert, asthey both meet different experiment needs, based on duration and capability.

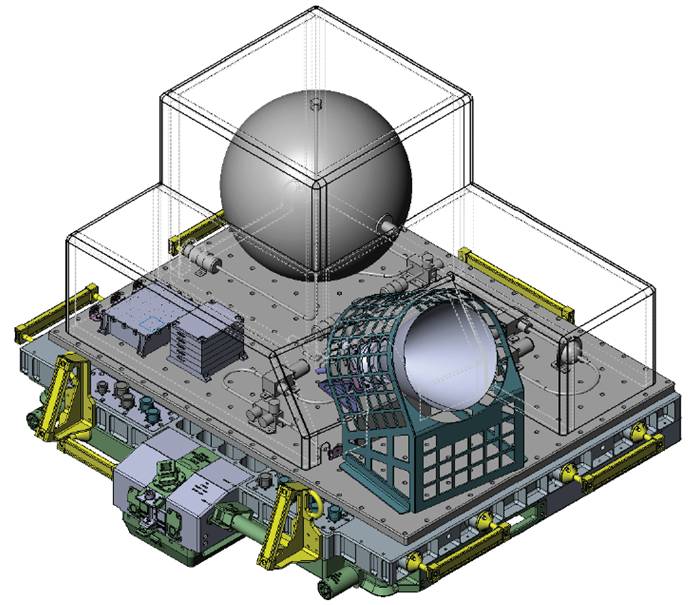

I’d like to point out that the space station also usesracks, though of a different design and capability, to house multiple studies.These racks, which are housed in each module, can hold several investigationsat once. As far as hands-on research, however, the space station at fulloperation gets 3,500 hours of crew time per year across the whole partnership.Our long-duration capabilities enable our investigations to run according tothe needs of the research, whether in repeatable, short-duration experiments orin longer, ongoing operations. The crew can also replicate studies immediately,under the right circumstances, to look into unexpected phenomena.

A Lab Aloft’s JessicaNimon: Alan, can you comment on current funding for suborbital flights?

Stern: There are two sources that come to mind.There’s a request for proposals from NASA’s Chief Technologist Bobby Braun’soffice. In their flight opportunities program, they just completed finalselection for suborbital payloads. It’s a very small program, but it’s a start.Along with that, they also did another request for proposals due June 24, 2011to select launch service providers and integrators—and just announced IDIQ[indefinite-delivery, indefinite-quantity] contracts with seven flight providerfirms.

A Lab Aloft’s Jessica Nimon: Tara, turning to the space station now. Wheredo you see the future of station research going?

Ruttley: When you look at where the space station isheaded, there are really two areas to examine. The station as a whole and theNational Lab. For the station at large, our international partners each havetheir own individual goals based on their governing agency and their scientificand political climates. NASA’s own space station research goals are dependenton our mission—currently this is driven by the NASA Authorization Act of 2010.So as a result, NASA focuses on areas of research that benefit spaceexploration, and relatively less fundamental physical and life sciences, thoughthey are certainly not excluded.

The second piece is the U.S. National Laboratory, with afocus on Earth benefits. The combination of these elements drives the use ofthe space station as a whole. So the future of station is to continue to marchtowards these mission directives and goals. As more users engage in NationalLab efforts, we will see more of those Earth benefits, as well. It is importantto mention, however, that any research done on station can have Earth benefits,even if that is not the original focus of the investigation.

A Lab Aloft’s Jessica Nimon: Where are your suborbital efforts headednext?

Stern: We do a number of things related to suborbitalflight at the Southwest Research Institute.We will launch our own payload specialists and payloads in this effort; currentlywe have nine launches funded and options on three more.

A Lab Aloft’sJessica Nimon: What do you hope to see ahead for orbitalresearch?

Stern: I think one of the things this decade willhopefully see—and which may amp up the space station program—is an effort tohost commercial payload specialists. Whether in government or commercial taxis,these payload specialists could stay weeks or months on station using the NationalLab. It’s hard to tell if this will happen, in the government world, but it wouldbe a great program for the space station. We had something like this forshuttle and I think it would benefit station, as well.

Ruttley: I think the real key is that efforts tohave commercial companies flying people into space are going to be importantfor both research on the space station and other flight opportunities. Witheasy access to both station and abbreviated platforms like suborbital flights,scientists will finally be unconstrained and able to do experiments where theysee fit. The discovery potential is amazing!

Tara Ruttley, Ph.D., is Associate Program Scientist for theInternational Space Station for NASA at Johnson Space Center in Houston. Dr.Ruttley previously served as the lead flight hardware engineer for the ISSHealth Maintenance System, and later for the ISS Human Research Facility. Shehas a Bachelor of Science degree in Biology and a Master of Science degree inMechanical Engineering from Colorado State University, and a Doctor ofPhilosophy degree in Neuroscience from the University of Texas Medical Branch.Dr. Ruttley has authored publications ranging from hardware design toneurological science, and also holds a U.S. utility patent.

Dr. Tara Ruttley

(NASA Image)

Alan Stern, Ph.D., is the Associate Vice President for Research andDevelopment for Southwest Research Institute Boulder, Colo. He also served asNASA’s associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate in 2007-2008.Stern is a planetary scientist and an author who has published more than 175technical papers and 40 popular articles. He has a long association with NASA,serving on the NASA Advisory Council and as the principal investigator on anumber of planetary and lunar missions. Stern earned a doctorate inastrophysics and planetary science from the University of Colorado at Boulderin 1989.

Alan Stern