by Joe Atkinson / HAMPTON, VIRGINIA /

Last year, the first in a series of five flight campaigns for Atmospheric Carbon and Transport-America, or ACT-America, sent researchers into the field at the blazing peak of summer.

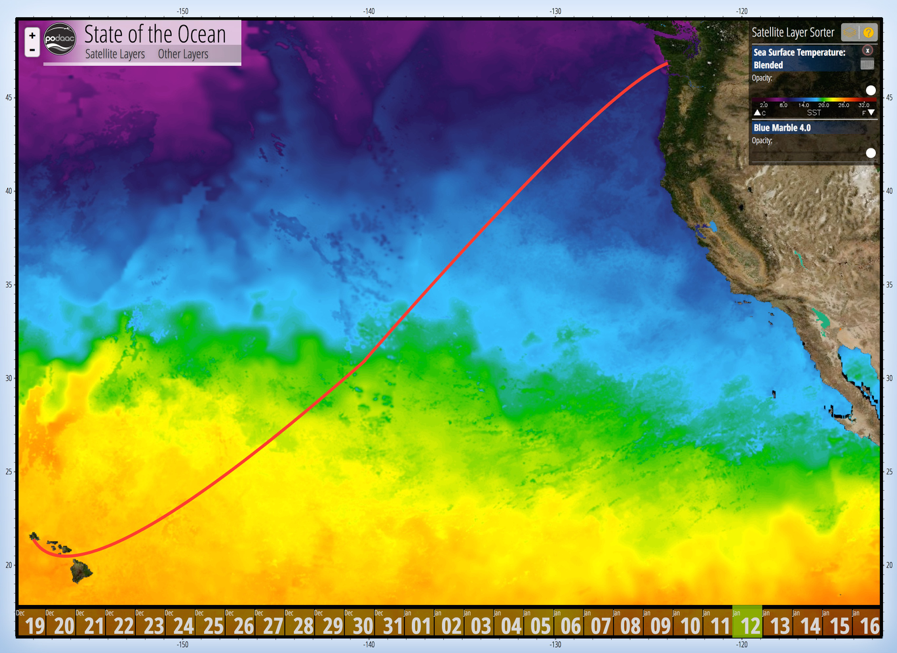

The flights were investigating how weather systems and other atmospheric phenomena affect the movement of carbon dioxide and methane in the atmosphere around the eastern half of the United States.

This year, those same researchers are doing it all again. And this time, they’re heading out during the deepest, coldest part of winter. Flights out of Shreveport, Louisiana, begin February 1. In coming weeks, ACT-America’s base of operations will move twice — once to Lincoln, Nebraska, and then to coastal Virginia.

So why trade one seasonal extreme for another?

“Because the carbon budget, especially when it comes to carbon dioxide, is highly seasonal,” said Ken Davis, ACT-America prinicpal investigator from Penn State University.

From summer to winter, the exchange of carbon dioxide between the biosphere on land and the atmosphere goes through some big changes.

“The biosphere is growing vigorously in the summer, taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere,” said Davis from his office at Penn State. “In the winter, it’s slowly breathing out — not a lot, because it’s cold. But it is slowly exhaling all winter long.”

The transport of greenhouse gases through the atmosphere can be quite different in winter as well. The jet stream plunges deeper south and tends to bring with it more intense storms. Those mid-latitude cyclones cause vigorous mixing of the gases in the atmosphere.

One thing that tends to stay relatively steady from season to season — human carbon emissions from the extraction and burning of fossil fuels.

What makes ACT-America unique is that it marks the first time aircraft outfitted to take advanced measurements of greenhouse gases have collected continuous data on how greenhouse gases are transported through the atmosphere by weather systems.

Previous measurements studying greenhouse gases have mostly come from tower-based measurement stations and satellites (one of ACT-America’s goals is actually to verify data coming in from NASA’s Orbiting Carbon Observatory-2 satellite), or from aircraft flying in fair weather conditions when atmospheric transport is relatively simple.

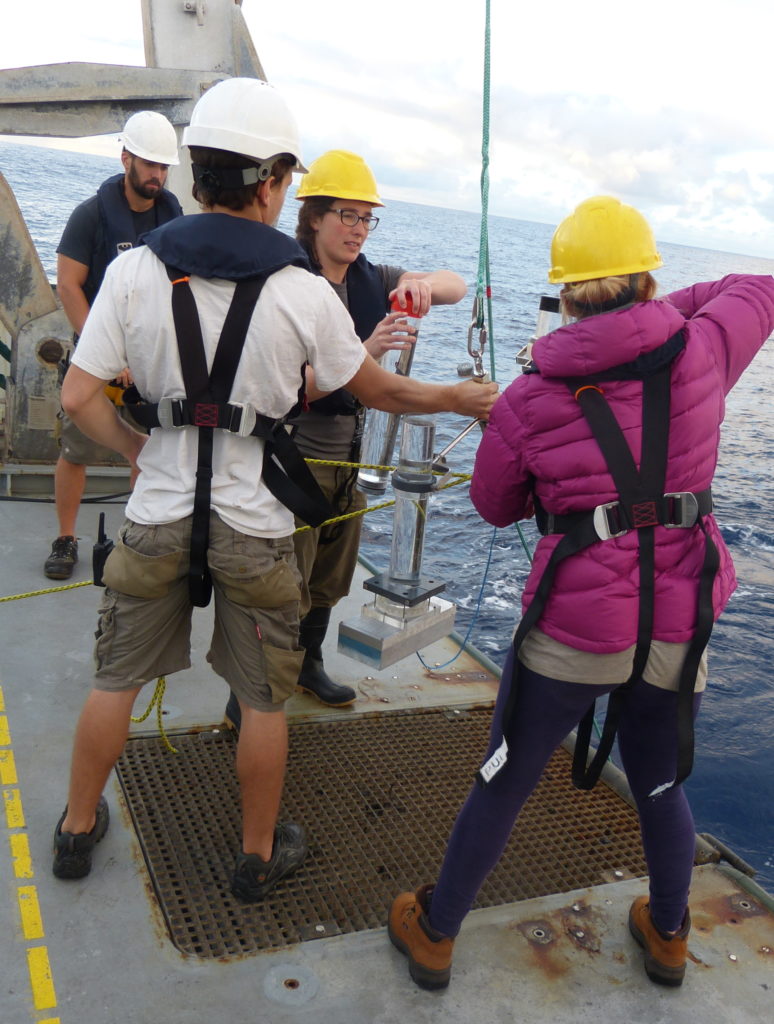

The campaign will use instruments on a C-130H based out of NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility on Virginia’s Eastern Shore and a King Air B-200 based out of NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia.

Davis believes the data the ACT-America team is collecting could help paint a much more detailed picture of what’s happening with greenhouse gases in the U.S.

“It’s our vision to enable the research community to monitor over time and space carbon dioxide and methane fluxes,” he said. “For example, if forests in the eastern U.S. become stressed by droughts and begin to de-gas their carbon stocks into the atmosphere, we want be able to detect it from atmospheric data and know quickly that we have a problem. And if measures are taken to reduce methane emissions from agriculture, and oil and gas extraction, we want to be able to verify that they’re proving effective.”

Breaking up the Intensity

That long-term vision motivates Davis as he faces what he refers to as “the intensity of the field deployment.”

To keep the intensity manageable, he finds little ways to decompress. The Penn State professor is an avid runner. Last summer, when he wasn’t on a flight or planning a flight or doing something related to the campaign, it wasn’t unusual to catch Davis in his unofficial uniform: a T-shirt, shorts and running shoes. That’s not likely to change for this flight campaign, regardless of the weather.

“That’s been my thing for a long time,” he said. “Get outside, go for a run.”

Davis also hopes to slow down and enjoy his surroundings — particularly in Virginia.

Last July wasn’t exactly the best time for that. From his temporary home base at Wallops, Davis ventured out to visit nearby Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge and Assateague Island National Seashore. The area is known for its pristine beaches, herds of wild ponies and migratory bird populations.

Unfortunately, when it’s warm, the area is also known for its hungry mosquitoes.

So Davis hopes the winter season will not only bring changes to concentrations of greenhouse gases, but also to concentrations of blood-sucking insects.

“We went out there in the summer and were eaten alive,” he said. “But I like the place and it should be fun to see it in the winter when we won’t be eaten alive.”