by Denise Lineberry / WOODS HOLE, MASSACHUSETTS /

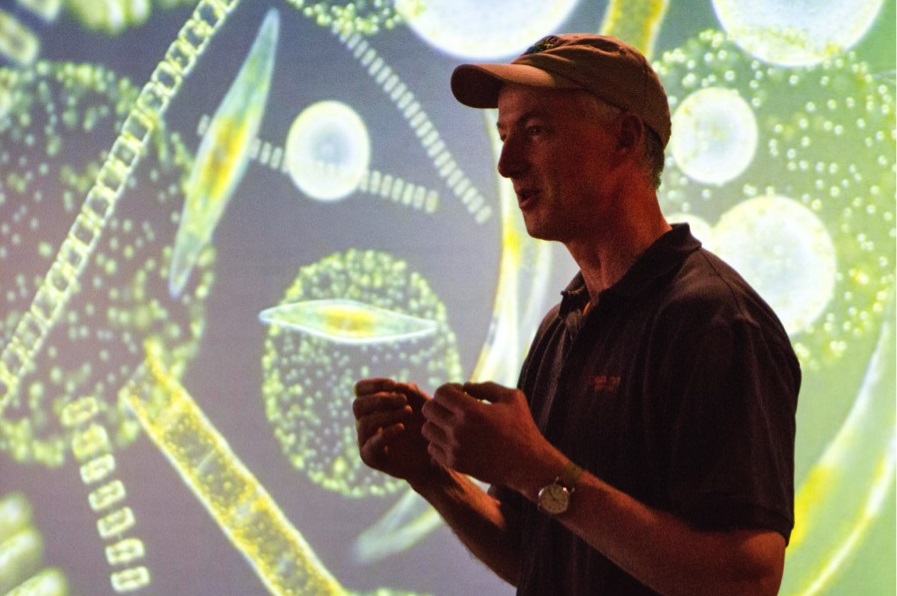

Each year the world’s largest phytoplankton bloom in the North Atlantic goes through distinct phases. In Fall, the plankton are declining after the summer climax. And there are many factors, such as sunlight, water depth, available nutrients and carbon, that control it. Understanding those processes enables more accurate forecasting of this bloom, and others, for ocean management and assessing ecosystem change.

With those goals in mind, for the third time NASA’s North Atlantic Aerosols and Marine Ecosystems Study, or NAAMES, has set sail.

On August 29, about 60 people—half NAAMES scientists and half crew—boarded the R/V Atlantis to test and strap down instruments before settling into their home away from home for the next month. On August 30, despite the possibility of stormy seas, they departed from Woods Hole, Massachusetts, for the wide open North Atlantic.

With it being the third deployment, the ship crew has some clear expectations on what they want to find out, some really cool instruments to get the data, and an undeniable sense of humor and comradery that has grown from doing life and science on a ship.

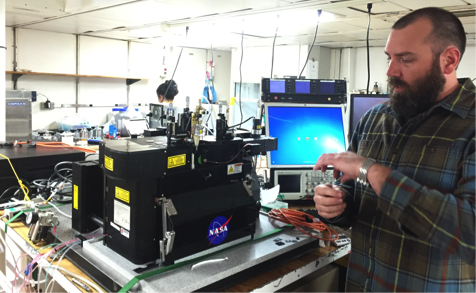

“James can be a bit cranky sometimes,” said Cleo Davie-Martin, a postdoctoral scholar at Oregon State University’s Department of Microbiology. But James isn’t a person, it’s a mass spectrometer that measures, or essentially sniffs out, volatile compounds from plankton that can move into the air.

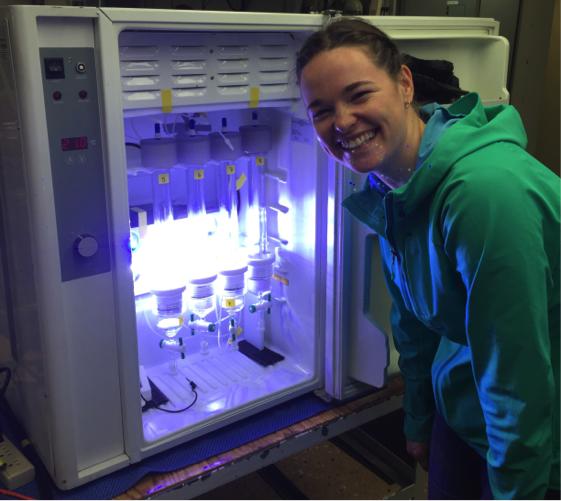

Some of the crew jokingly refers to the ship’s main lab as the ‘meat locker’ due to the low temperatures needed to maintain the integrity of samples collected and stored by several groups who study the microbial food web. Scenes there include bundled up scientists among rows of tables with latched down filtration systems, microscopes, imagers, monitors and countless other scientific tools.

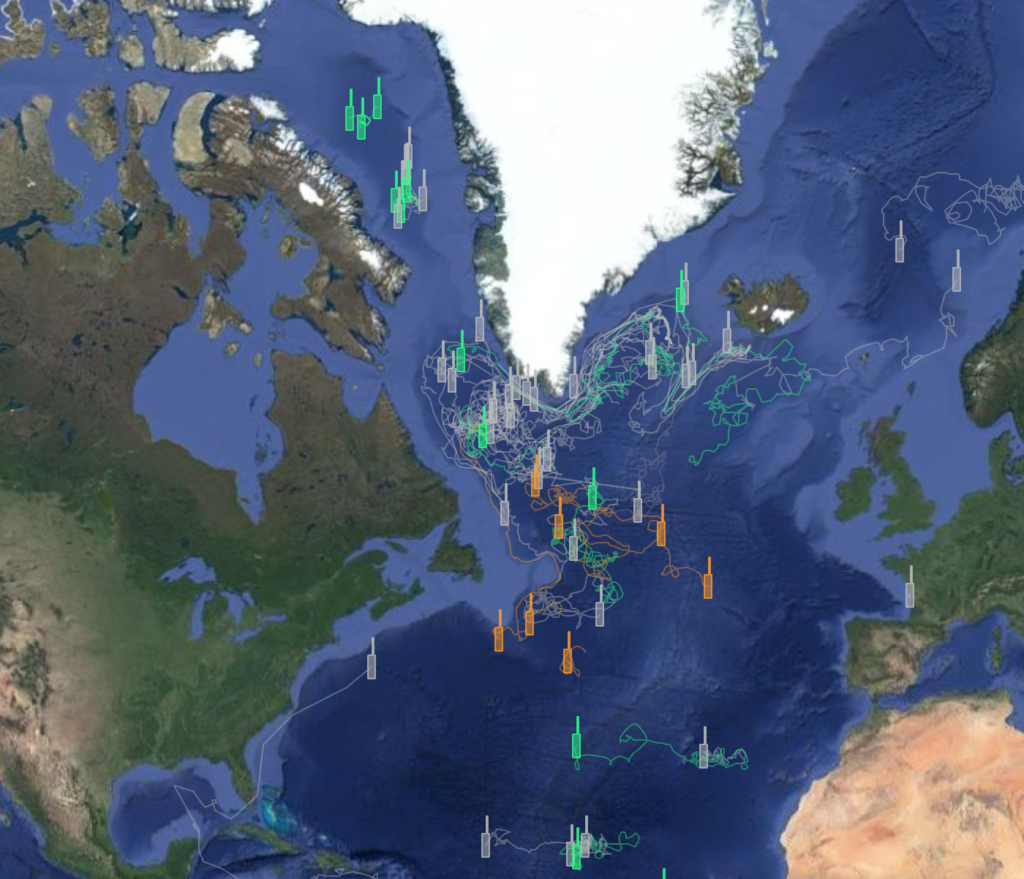

The floats used for NAAMES are definitely not your average float. In fact, they sink. But depending on the type of float used and depth they sink to, they return to the surface within two to six hours with data on the vertical structure of the ocean, salinity, pressure, light, chlorophyll, oxygen and more. These important bits of data are key to understanding phytoplankton growth and decline.

Using an Iridium Antenna, the floats can be powered and tracked.

“It’s basically like AT&T for satellites,” said Nils Haëntjens, an oceanography student from the University of Maine, as he began testing and calibrating the floats prior to departure.

The Atlantis has planned stations that serve as research pit stops for the crew. Just before and while at each stop, they toss about three drifters out to sea. The drifters do float, but more importantly, they drift.

“Drifters help us to do research, because while we stay in one spot at a station, they can move about 20 miles within four days,” said Peter Gaube, research scientist from the University of Washington’s Applied Physics Laboratory.

While at sea, the Gulf Stream current carries the drifters through eddies like a skier going through moguls. There are 60 drifters aboard Atlantis and the crew will sign up for slots to toss a drifter. But first, they get to name and decorate them with paint.

The drifters track changes in the physics of the water over time, providing a snapshot of water properties back to the ship. And often times, they continue to provide this data long after the ship has returned to port.

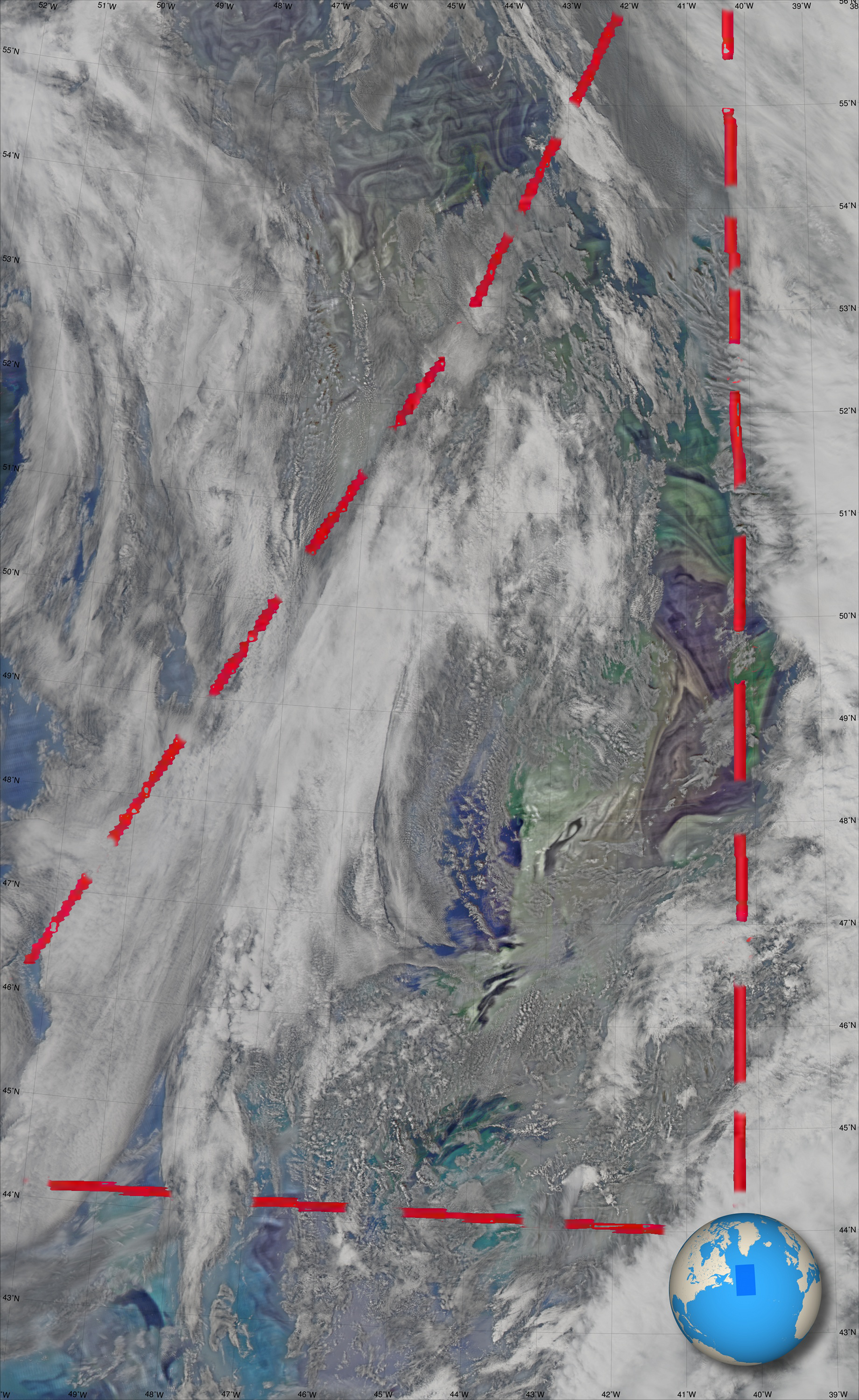

The sensors on the drifters serve as tiny breadcrumbs for NASA’s C-130 as it flies over the North Atlantic to eventually fly over the Atlantis. The drifters report current positions that allow the aircraft to measure the same locations as the ship.

From space, satellites play an integral role in measuring what’s over the plane. From 20,000 to 30,000 feet in the air, the aircraft validates down-looking measurements from space. And the Atlantis and its full suite of measurements provide ground, or ocean, truth to aircraft and space measurements.

Other instruments aboard Atlantis study ocean optics, atmospheric aerosols, cloud condensation, dissolved organic carbon, cell characterization, growth rates, species composition and predation, grazing and mortality of plankton.

The combined ship-airborne measurement strategy used by NAAMES makes a critical contribution to the ocean ecosystem scientific record by capturing the full range of scales of the plankton ecosystem.

Stay tuned, as NASA’s C-130 is in St. John’s, Newfoundland, preparing to follow the drifting breadcrumbs for its first of many science flights during the fall 2017 campaign.