In today’s A Lab Aloft entry, guest blogger and European Space Agency astronaut Christer Fuglesang talks about his role as a test subject while living aboard the International Space Station.

You may not know it, but being an astronaut also means being a guinea pig. A lot of the research done in space is about humans, in particular how our bodies are affected by the weightlessness. This is important to know in order to prepare ourselves for future human exploration, like when we will travel to Mars. But this research also gives us many new insights in how our bodily systems work. This knowledge can help scientists and doctors to improve medical treatments here on Earth. They can even find new and better ways to prevent illnesses based on microgravity studies.

European Space Agency astronauts Frank De Winne and Christer Fuglesang photographed during the installation of the new Minus Eighty Degree Laboratory Freezer for ISS, or MELFI, in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station. (NASA Image)

Virtually every astronaut that has ever gone into space has participated in medical experiments as a test subject – or as I like to call it, a guinea pig. The inhabitants of the International Space Station almost daily have some activity related to human research. During a workout, for instance, we take measurements like blood pressure, heart rate, or body temperature to provide valuable research data.

Some studies, like the Neuroendocrine and Immune Responses in Humans During and After Long Term Stay at ISS, or Immuno, require taking a saliva sample to check the immune system. Then there’s the Nutrition Status Assessment, or Nutrition, which requires blood and urine samples that store in the Minus Eighty Degree Laboratory Freezer for ISS, or MELFI, aboard the station. They later return to the ground for analysis. Another investigation that comes to mind is Bodies In the Space Environment: Relative Contributions of Internal and External Cues to Self – Orientation, During and After Zero Gravity Exposure, or BISE, which measures brainwaves while the astronaut performing some visual tasks to investigate how microgravity affects the neurological system.

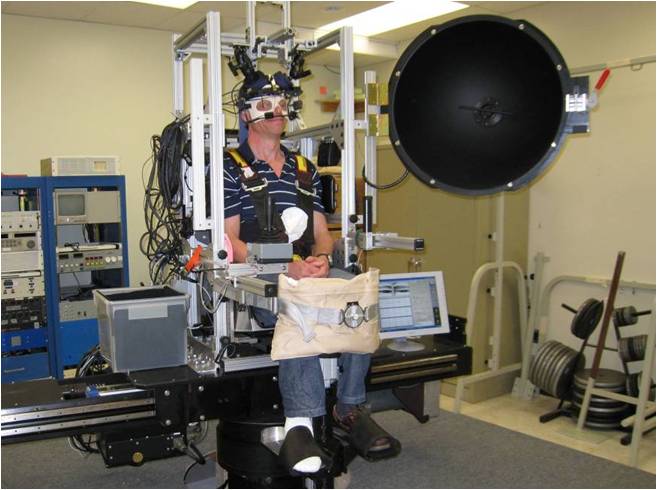

European Space Agency astronaut Christer Fuglesang trains for the Otolith Assessment During Postflight Re-adaptation, or Otolith, investigation prior to his departure to the International Space Station. (Credit: Christer Fuglesang)

It seems that almost every system in our bodies gets more or less affected by weightlessness: from muscles and bones to cells in the immune system, from the heart and lungs to eyes and the balance organs in the ears. Humans are designed to live in a 1-g environment, making their long-term exposure to microgravity a fascinating and biologically altering study of the entire body.

In my case, I have specifically participated in several experiments related to the balance system, or vestibular system, such as the Otolith Assessment During Postflight Re-adaptation, or Otolith, and the Ambiguous Tilt and Translation Motion Cues After Space Flight, or Zag. Before and after my flights, I stood on wobbling plates and sat in spinning and sliding chairs, trying to keep my balance or perform some set of actions.

Meanwhile, scientists observed me and compared my responses from before flight with how I performed right after about two weeks in weightlessness. They also looked into how my balance regained normality during the week after returning to Earth. This helped them to understand new things about how humans keep our balance. This knowledge may eventually help doctors to better diagnose people who have medical disorders like disorientation and nausea.

Canadian astronaut Robert B. Thirsk wears sensors and hardware in preparation for the Canal and Otolith Interaction Study, or COIS, another vestibular system investigation. (NASA Image)

In almost all science, doing an experiment one time is not enough. This is particularly true in human research, since each test subject is somewhat different. Therefore, some 10 other astronauts also performed the above-mentioned experiment. As one can understand, with only so many crew members on orbit at a given time, it takes awhile to get enough guinea pigs to complete a round of human research in space.

These studies are well worth it, however, as is the discomfort of sitting in a chair that spins with 400 rotations per minute while sliding sideways. The research is important and yields unique results for the benefits of humans, both in space and on Earth.

Christer Fuglesang

(NASA)

Christer Fuglesang is an astronaut with the European Space Agency, or ESA. He flew as a Mission Specialist with STS-116 and STS-128 to the International Space Station where he participated in multiple extravehicular activities, or EVAs. He is the first Swedish astronaut to fly in space.