In today’s A Lab Aloft, guest blogger Fred Kohl, Ph.D., International Space Station Physical Sciences Research project manager at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, talks about some of the physical science investigations that take place in microgravity aboard the space station.

Extremes are part of exploration, whether you’re talking about space travel or probing new areas of discovery to expand knowledge in a given science. So it is appropriate that the extreme environment of the International Space Station provides an ideal location to study physical sciences, from flames to fluids.

Removing gravity from the equation aboard this Earth-orbiting laboratory reveals the fundamental aspects of physics hidden by force-dependent phenomena where a fluid phase (i.e., a liquid or gas) is present. Such experiments, which investigate the disciplines of fluid physics, complex fluids, materials science, combustion science, biophysics and fundamental physics, use the station’s specialized experiment hardware to conduct studies that could not be performed on the ground.

The main feature differentiating the space station laboratory from those on Earth is the microgravity acceleration environment that is stable for long periods of time. Conducted in the nearly weightless environment, experiments in these disciplines reveal how physical systems respond to the near absence of buoyancy-driven convection, sedimentation, or sagging. They also reveal how other forces, which are small compared to gravity, can dominate the system behavior in space. For example, capillary forces can enable the flow of fluids in relatively wide channels without the use of a pump.

Other examples of observations in space include boiling in which bubbles do not rise, colloidal systems containing crystalline structures unlike any seen on Earth, and spherical flames burning around fuel droplets. Also observed was a uniform dispersion of tin particles in a liquid lead melt, instead of rising to the top as would happen in Earth’s gravity.

These findings may improve the understanding of material properties, potentially revolutionizing development of new and improved products for use in everything from automotives to airplanes to spacecraft. With so much to learn in the area of physical science and so many investigations, I would like to highlight several studies ongoing, upcoming or recently looked at aboard the space station.

Constrained Vapor Bubble-2 (CVB-2)

Studying mixed fluids in microgravity for CVB-2 provides data to further optimize the performance of wickless heat pipes. These pipes weigh less and have reduced complexity as compared to the more common construction with a wick. The CVB-2 study examines the overall stability, fluid flow characteristics, average heat transfer coefficient in the evaporator, and heat conductance of a constrained vapor bubble under microgravity conditions as a function of vapor volume and heat flow rate.

Findings from this research may lead to more efficient ways to cool electronics and equipment in space, while also applying to advances in Earth technologies such as air conditioning and refrigeration systems. Laptop computers also use this type of heat pipe technology to cool their electronics in order to prevent overheating.

Advanced Colloids Experiment (ACE)

ACE studies colloidal particles in space for use in modeling atomic systems and engineering new systems. These particles are big enough—in comparison to atoms—to be seen and recorded with a camera for evaluation. Conducting this study aboard the space station removes gravitational jamming and sedimentation so that it is possible to observe how order rises out of disorder, allowing researchers to learn to control this process. This could lead to greater stability and longer shelf life for products on Earth, such as paints, pharmaceuticals and other products based on colloids. Recently we launched additional hardware, consisting of a magnetic mixer and a drill kit, to use in mixing the samples for future ACE experiments.

Capillary Flow Experiment-2 (CFE-2)

The CFE investigation is a suite of fluid physics flight experiments designed to study large-length scale capillary flows and phenomena in low gravity. Testing will probe dynamic effects associated with a moving contact boundary condition, capillary-driven flows in interior corner networks, and critical wetting phenomena in complex geometries. The sample fluids flow in specific directions influenced by the shape of unique cylindrical containers called Interior Corner Flow (ICF) vessels.

For CFE-2 there are 11 units of fluids for astronauts to test. This research and the resulting math models based on the data findings helps with the design of more efficient fuel systems for spacecraft. This is because the engineers will be able to design the shape of the tank to take advantage of the way fluids move in microgravity. On Earth these findings may contribute to models to predict fluid flow for things like ground water transport, as well as the afore mentioned cooling technology advances for electronics.

Flame Extinguishment Experiment – Italian Combustion Experiment for Green Air (FLEX-ICE-GA)

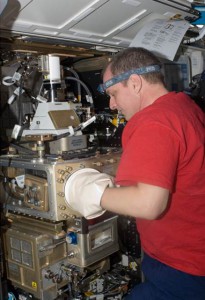

The objective of this investigation is to observe and characterize evaporation and burning of renewable-type fuel droplets in high-pressure conditions. Test runs for this study recently took place in the Combustion Integrated Rack (CIR) aboard station. Research conducted in the CIR facility includes the study of combustion of liquid, gaseous and solid fuels. The CIR is made up of an optics bench, combustion chamber, fuel and oxidizer control, and five different cameras for performing combustion experiments in microgravity.

Researchers can use the results of these experiments to develop and validate thermo-chemical and chemical kinetics computer models of renewable liquid fuels for combustion simulation in engines. This helps with the design of the next generation of fuels and advanced engines. The computer models may reduce costs to industries and benefit the general public by accelerating the adoption of renewable fuels that are environmentally friendly.

Supercritical Water Mixture (SCWM)

The SCWM investigation will help researchers look at phase change, solute precipitation, and precipitate transport at near-critical and supercritical conditions of a dilute salt/water mixture. When water is taken into its supercritical phase—a temperature higher than 705 degrees Fahrenheit and a pressure higher than 3,200 psia—it becomes highly compressible and begins to behave much like a dense gas. In its supercritical phase water will experience some rather dramatic changes in its physical properties, such as the sudden precipitation of inorganic salts that are normally highly soluble in water at ambient conditions.

The primary science objectives of the SCWM investigation are to determine the shift in critical point of the liquid-gas phase transition in the presence of the salt, determine the onset and degree of salt precipitation in the supercritical phase as a function of temperature, and to identify the predominant transport processes of the precipitate in the presence of temperature and/or salinity gradients.

On Earth water reclamation from high-salinity aquifers, waste handling for cities and farms, power plants, and numerous commercial processes may benefit from the SCWM findings. A good understanding about the behavior of salt in near-critical and supercritical conditions also would assist designers of the next generation of reactors. With the knowledge gleaned from SCWM, they could possibly design systems that would operate without incurring large maintenance problems.

With the still relatively new frontier of microgravity research, there are many questions to pose and angles to consider. The scientists that pursue the answers using the laboratory we have available 200 miles above us are embarking on a journey of discovery that I dare say will yield some amazing findings. As Albert Einstein said, “To raise new questions, new possibilities, to regard old problems from a new angle, requires creative imagination and marks real advance in science.”

Fred Kohl is the International Space Station Physical Sciences Research project manager at Glenn. Since the mid-1980s, he’s been involved in the advocacy, definition, development and conduct of more than 250 experiments in ground-based facilities and aboard the space shuttles, Mir space station and the International Space Station in the disciplines of fluid physics, complex fluids, combustion science, fundamental physics, materials science and acceleration environment characterization. Before joining the microgravity program, he conducted research in high-temperature materials chemistry and high-temperature materials corrosion related to aircraft engine applications. He holds a B.S. in chemistry from Case Institute of Technology and a Ph.D. in chemistry from Case Western Reserve University.

A very interesting post with easily understandable information. Thank you