In today’s A Lab Aloft entry International Space Station Program Scientist Julie Robinson, Ph.D., continues the countdown to her top ten research results from the space station, recently presented at the International Astronautical Conference in Beijing, China. Be sure to check back for daily postings of the entire listing.

Number eight on my list of the top ten research results from the International Space Station is hyperspectral imaging for water quality in coastal bays. This is an important research result because it shows the value of the space station as an Earth remote sensing platform. In this case, the space station hosts an instrument called the Hyperspectral Imager for the Coastal Ocean (HICO).

This imager gets data on the wavelengths of light that it measures reflecting back from the surface of the Earth. It is particularly tuned to get hundreds of bands, much more than the eight different bands you would usually get from a remote sensing instrument like Landsat. These hundreds of different bands can be teased apart for details and information that you can’t get from normal remote sensing data.

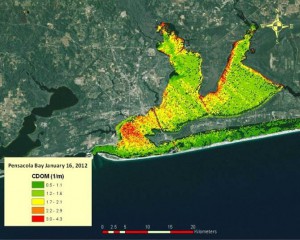

For example, using HICO you can distinguish between sediment and chlorophyll in the water column. Chlorophyll, which is a sign of algae, is an indicator that nitrogen is flowing in—say from fertilizers on the land. That is an important marker of water quality issues. In a sediment-laden bay, however, it can be really difficult to differentiate between the two—often called the “brown water” problem by ocean remote sensing experts.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) used HICO to develop a proof-of-concept to help monitor and protect our water supplies as required by the nation’s Clean Water Act. The work was originally funded by the EPA under a Pathfinder Innovation Project Award. The results were honored with a top research application award at the 2013 International Space Station Research and Development Conference. Darryl Keith, Ph.D., accepted the award on behalf of his research team regarding their work using HICO to gather imagery for ocean protection for the EPA.

EPA researchers went out and timed collections of their field observations with an over-flight of the space station. The scientists were able to put the data together to get better measurements for dissolved organic matter and chlorophyll A. This allowed them to develop models that suggest the presence of algal blooms, which present a danger to the health of sea life.

With the HICO proof-of-concept in hand, EPA researchers now are interested in using these models to develop an app that anyone can use to obtain real-time water quality information. The goal is to have algorithms that don’t require coordinating the space station or satellites with field data. The success of such a venture would mean real-time updates without anyone having to go into the field. This kind of an application developed by another government agency is really important for showing the broad value of the space station.

HICO has been converted into a space station facility, with open access for both users funded by NASA’s Earth Science Division, and also commercial users sponsored by the Center for the Advancement of Science in Space (CASIS) to use space station as a National Laboratory. Both organizations have announced opportunities to use the instrument. This is just the first of a number of remote sensing instruments headed for the space station that will transform the way this orbiting laboratory serves our need for data about the Earth below.

Julie A. Robinson, Ph.D.

International Space Station Program Scientist

That’s really cool! A great answer to ‘why do we spend so much money up there when we should spend more money down here’ question. I wish I could visit the ISS!