by Joy Ng / WESTERN COLORADO /

As I walked down the aisle of a plane with a camera clasped between my two sweaty palms, I had two thoughts on my mind: First, my footsteps feel very heavy; second, I hope I can film without vomiting. As you might guess, this was no ordinary flight.

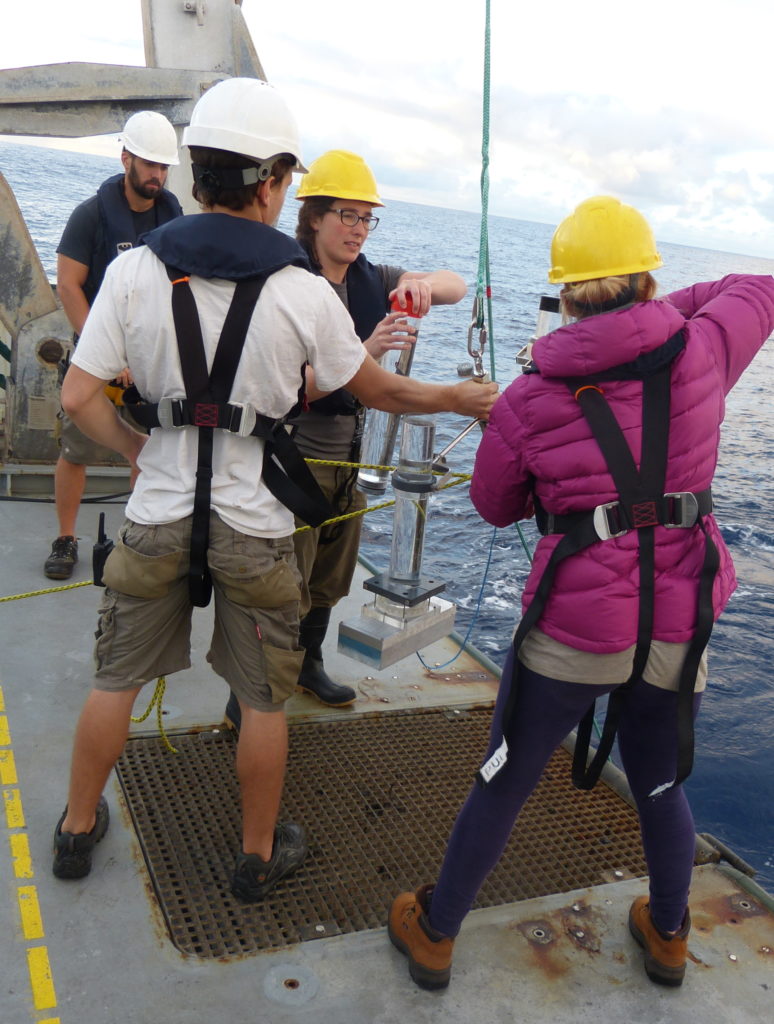

Why did this flight feel like a nauseating roller coaster ride? The Navy’s P-3 Orion aircraft was outfitted with a variety of instruments that required various flying maneuvers to collect data. The plane flew back and forth in a straight line and around in tight circles. It was literally a dizzying dance in the air.

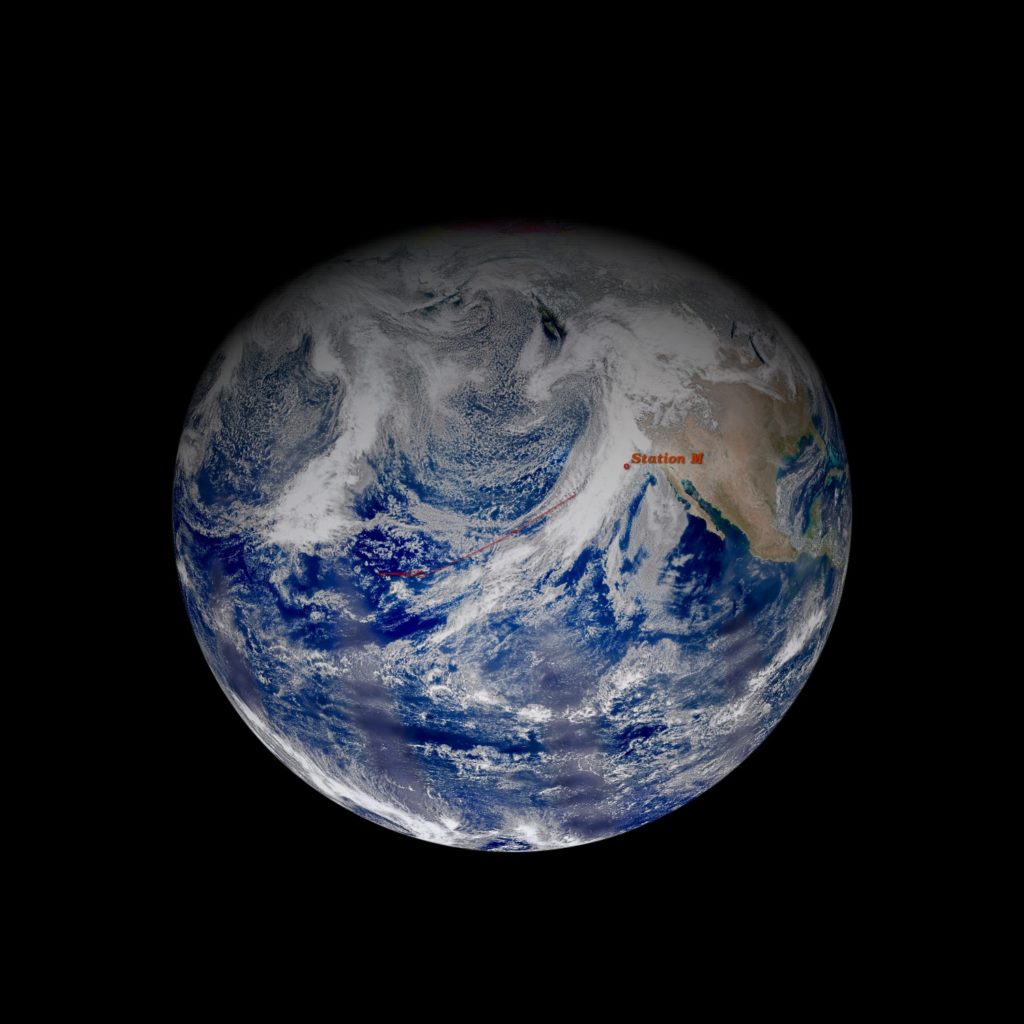

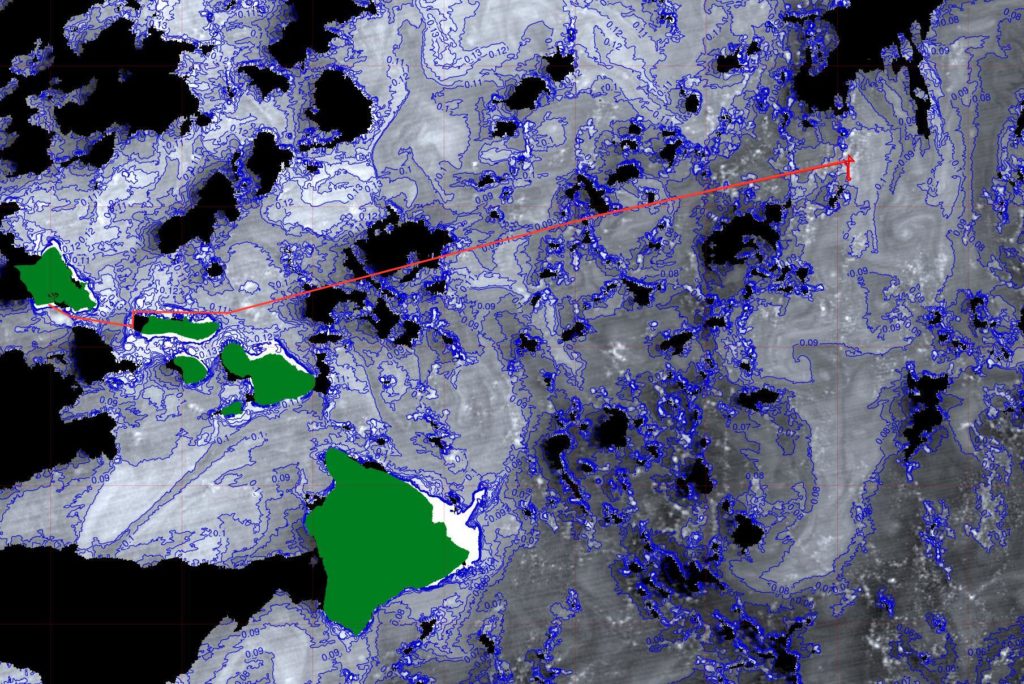

This science flight was carried out as part of a new NASA-led campaign called SnowEx. At the moment, we have satellites that can see snow cover but no instruments in space that can accurately measure how much water they hold. Such a measurement is important, considering that roughly one-sixth of the world’s population relies on snow for their water resources. The campaign is exploring instruments and technologies for measuring snow that may eventually result in a snow-observing satellite.

One of the biggest land areas where snow falls is boreal forest, so SnowEx chose its first flights over the forests of Grand Mesa and Senator Beck Basin in western Colorado. Because leaves and branches can act like obstacles for some snow-measuring instruments, scientists are using these forests to investigate what combination of instruments can successfully measure snow over this kind of terrain.

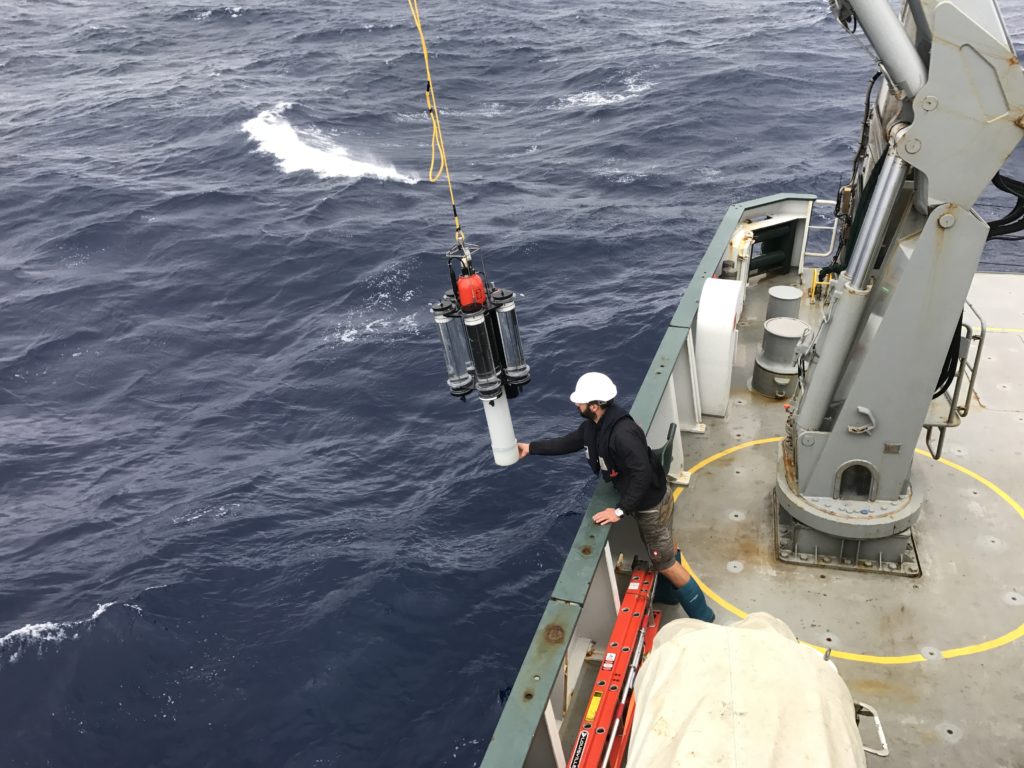

At the same time, scientists are working on ‘ground-truthing’ the airborne measurements. This involves more than 100 scientists measuring snow depth and density on the ground to get accurate snow measurements that can validate the measurements taken by the airborne instruments.

Collecting these in-flight measurements is tricky. Each instrument works at specific altitudes, over specific types of snow, and only in certain types of weather. This means that the aircrew and scientists have to work together to come up with a detailed flight plan—one that can change day to day—that allows all instruments to collect data successfully.

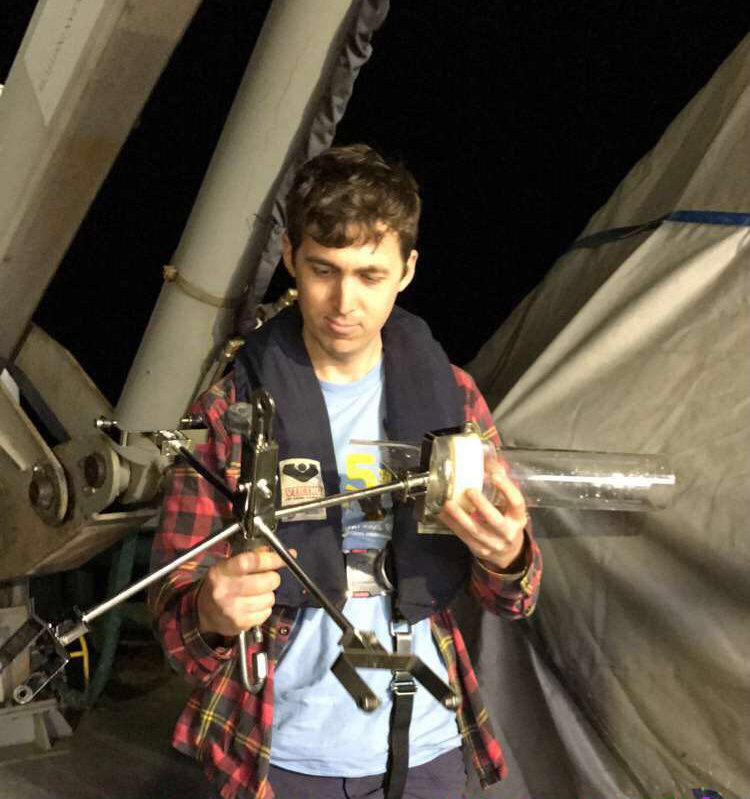

While I was on the plane, most of the scientists were in seats next to their instruments. I, on the other hand, was swerving side to side as I did my own little dance to capture my shots. It’s not the ideal film set. The light is constantly changing. Every surface of the plane is vibrating and it’s very loud. In these conditions, I had one priority in mind: stabilization. Luckily, I used a handheld gimbal—an electronic device that counteracts any minor movements—that allowed me to film smooth shots while my feet were to the contrary.

I managed to capture some great footage and discovered that, for me, the mountaintop views were a good remedy for any motion-induced mishaps.