As a 30 year-old research assistant at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, I have a unique perspective of the Apollo missions. I was not alive when humans last walked on the moon; the Apollo missions were part of my parents’ generation. With live televised coverage from the lunar surface and glossy photo spreads in magazines, places like Tranquility Base, the Descartes Highlands, and Fra Mauro became familiar during the Apollo program. However after the final Apollo mission left the moon, many forgot these significant lunar landmarks. That changes today. With the amazing images of the Apollo landing sites taken through NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), the Apollo landing sites are once again significant for today’s generation.

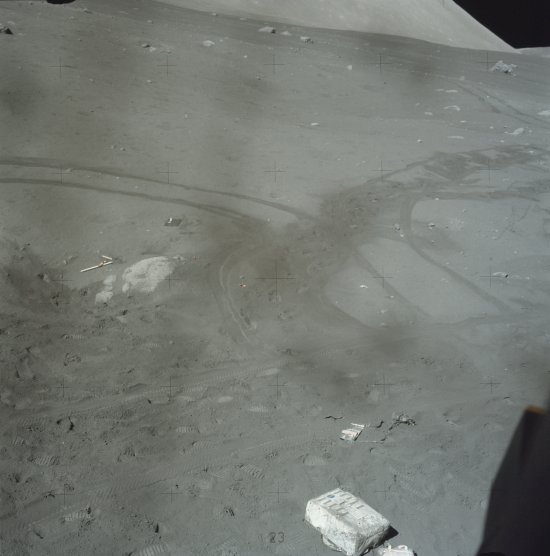

These images from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), released July 17, show

five of the six Apollo landing sites with arrows pointing out the lunar descent

module visible resting on the lunar surface. (NASA/GSFC/ASU)

View other images of the moon in our blog’s Flickr gallery.

The Apollo landing sites are no longer simply historic sites revealed through 40 year-old images taken by the Apollo astronauts. Instead, they are dynamic landscapes that can be seen in a new light through LRO. These special areas on the moon now have a new life, with the help of a reminder that 40 years ago humans spent days exploring the surface of our neighbor in space.

For me, these photos have an additional dimension as they remind me of why I’ve always been interested in the moon. In the mid 1960s my father worked on the Apollo program, building parts for the astronauts’ backpacks, known as the Portable Life Support Systems (PLSS). At the end of each lunar landing mission, in order to reduce the mass launched into lunar orbit, the astronauts would toss the PLSS’ onto the lunar surface; they were left behind and quickly forgotten. However, those who built the PLSS did not forget them. Before the packs were finished and shipped off, the engineers would etch their signatures on parts of the PLSS frame. So when the packs were left on the moon, the signatures also remained as a permanent monument to their achievements. So now when I look at these amazing photos, I can’t see those backpacks in these images, future images of the sites may show them, but I do see places where my dad’s name will be found forever.

This photo from the Apollo 17 mission shows the Portable Life Support Systems

backpack that Noah’s father worked on in the foreground. (NASA)

LRO is an important mission for lunar scientists for many reasons. For me one of the most important reasons is that we’ll address many science questions that we’ve come up with in the 40 years since Apollo 11. How many craters have formed on the moon in the last 40 years? How deep are all those craters? LRO data will also help us plan for sending humans back to the moon, we’ll be able to find the safe and scientifically interesting places where humans can explore. So for the next decade or so, we will turn to data from LRO to select the places we want to send astronauts to for long periods of time. If I can’t be one of those astronauts, hopefully I’ll be able use the data from LRO to help train the astronauts that will go there. While the Apollo missions might have been for my parents’ generation, LRO is also for my generation, and for the generations that will follow. And maybe, one day, I’ll be able to get my name onto the lunar surface too!

Noah Petro, lunar geologist