So how can we tell that the Russian meteor isn’t related to asteroid 2012 DA14?

One way is to look at meteor showers — the Orionids all have similar orbits to their parent comet, Halley. Similarly, the Geminids all move in orbits that closely resemble the asteroid 3200 Phaethon, which produced them. So if the Russian meteor was a fragment of 2012 DA14, it would have an orbit very similar to that of the asteroid.

It does not…

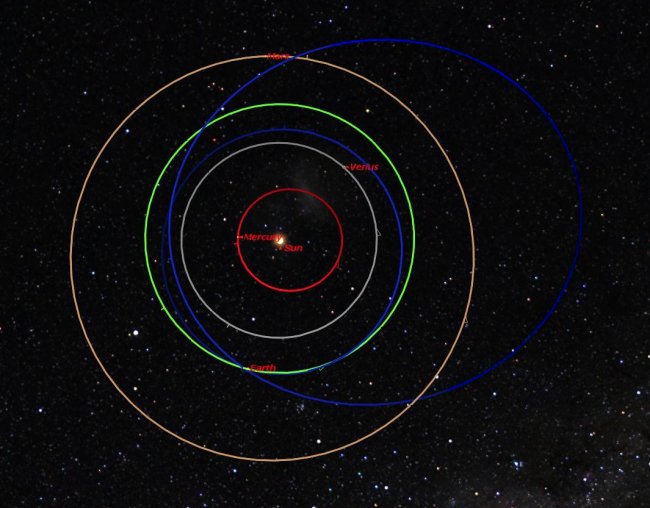

If you look at the image, the orbit of the Earth is the green circle. That of 2012 DA14 is the blue ellipse that is almost entirely within the orbit of the Earth; notice that it is close to circular. The other blue ellipse, stretching way beyond the orbit of Mars, is the first determination of the orbit of the Russian meteor. Notice that the two are nothing alike; in fact, they aren’t even close.

This is one reason — a big one — why NASA says the asteroid 2012 DA14 are not connected.

Text/image credit: NASA/MSFC/Meteroid Environment Office