I am asked this question over and over again, and it’s a good one. Everyone knows that you have to be in the right place to observe solar eclipses and other astronomical goings-on, so why should meteor showers be any different?

You do have to be in the right part of the planet to view meteor outbursts or storms, because the trails of comet debris are so narrow (hundreds of thousands of miles) that it only takes a few hours for the Earth to pass through the stream. A few hours is not enough time for the Earth to do a complete rotation (which takes 24 hours), so only those people located in areas where it is night and where the radiant is visible will be able to see the outburst or storm. These dramatic events require the viewers to be in the right ranges of both latitude AND longitude.

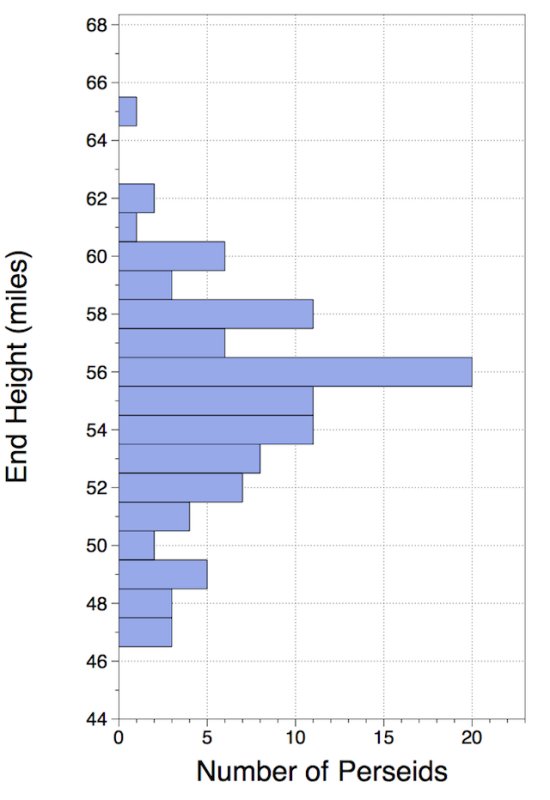

This is not true for normal meteor showers, like this year’s Perseids. The main stream of particles extends for millions of miles along Earth’s orbit, requiring days for it to cross. All we need is one day to take the longitude out of the visibility calculations, because then the entire planet will experience night while the shower is still going on. That’s the good news.

The kicker is that we not only have to have darkness, but also the radiant — in this case, located in the constellation of Perseus — has to be visible, i.e. above the horizon. The elevation of the radiant depends in part on latitude of the observer, and one can derive — or look up, in this age of Google — a relatively simple equation that gives the maximum elevation of the radiant:

maximum elevation = 90 – |dec -lat|

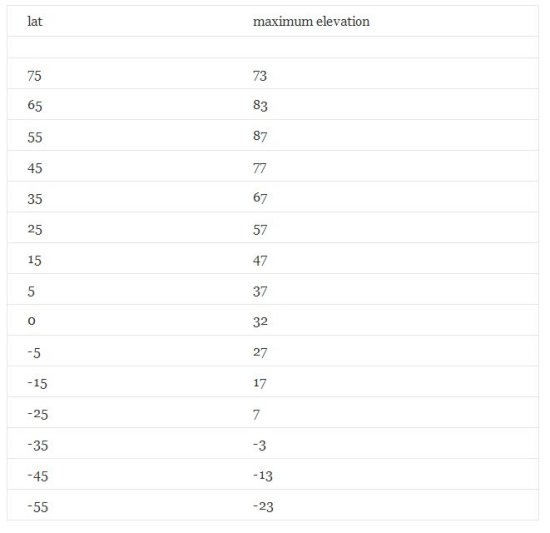

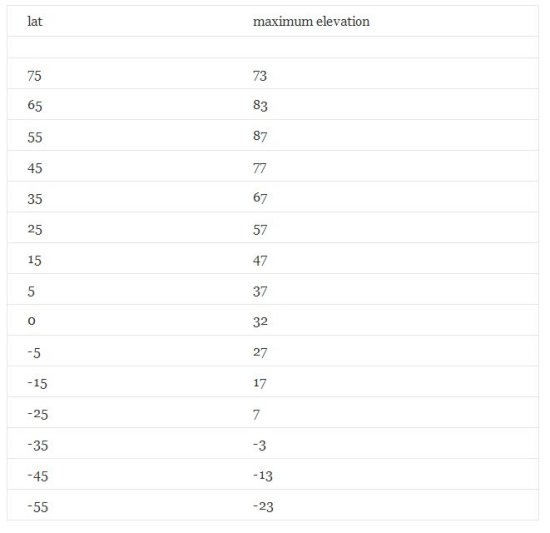

where dec is the declination of the radiant and lat is latitude of the observer (all in degrees). The vertical lines before dec and after lat mean to take the absolute value of dec — lat. In order to see meteors from the shower, the maximum elevation must be 0 or greater (preferably more than 15 degrees). In the case of the Perseids, dec = 58 deg, so it is easy to calculate the maximum elevation for various latitudes:

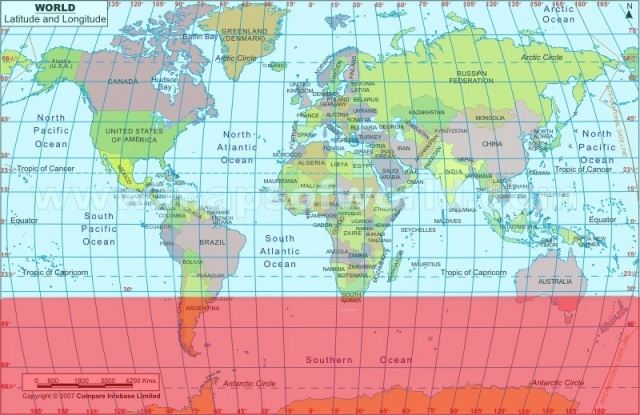

We see that everyone in the northern hemisphere has a shot at seeing Perseids (weather permitting), but folks south of -32 degrees latitude get the shaft.

On the world map above, the red shaded area is the region where the Perseids will not be visible. If you live south of Brazil, at the very southern tip of Africa, or southern Austrailia, you need to take a road trip to the North if you wish to see Perseids. If you want see decent numbers, it will be a long ride, as you need to trek to somewhere above -17 degrees latitude.

So will I see Perseids? You can find out on your own — look up your latitude (remember, Google is your friend), use the equation above, stick in 58 degrees for the dec, and calculate the maximum elevation. If it is above 15 degrees, you are good.

Remember to get away from city lights. A dark sky is important.

Enjoy the show!