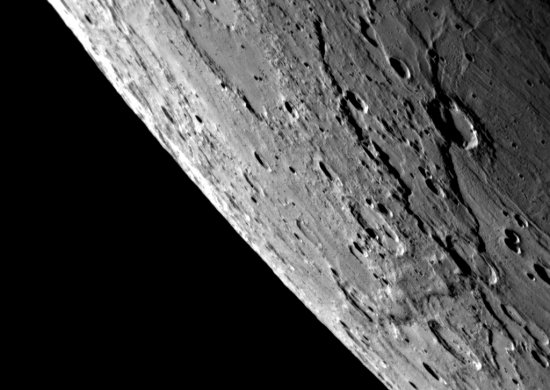

The sky will put on a show Nov. 11 when Mercury journeys across the Sun. The event, known as a transit, occurs when Mercury passes directly between Earth and the Sun. From our perspective on Earth, Mercury will look like a tiny black dot gliding across the Sun’s face. This only happens about 13 times a century, so it’s a rare event that skywatchers won’t want to miss! Mercury’s last transit was in 2016. The next won’t happen again until 2032!

“Viewing transits and eclipses provide opportunities to engage the public, to encourage one and all to experience the wonders of the universe and to appreciate how precisely science and mathematics can predict celestial events,” said Mitzi Adams, a solar scientist in the Heliophysics and Planetary Science Branch at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. “Of course, safely viewing the Sun is one of my favorite things to do.”

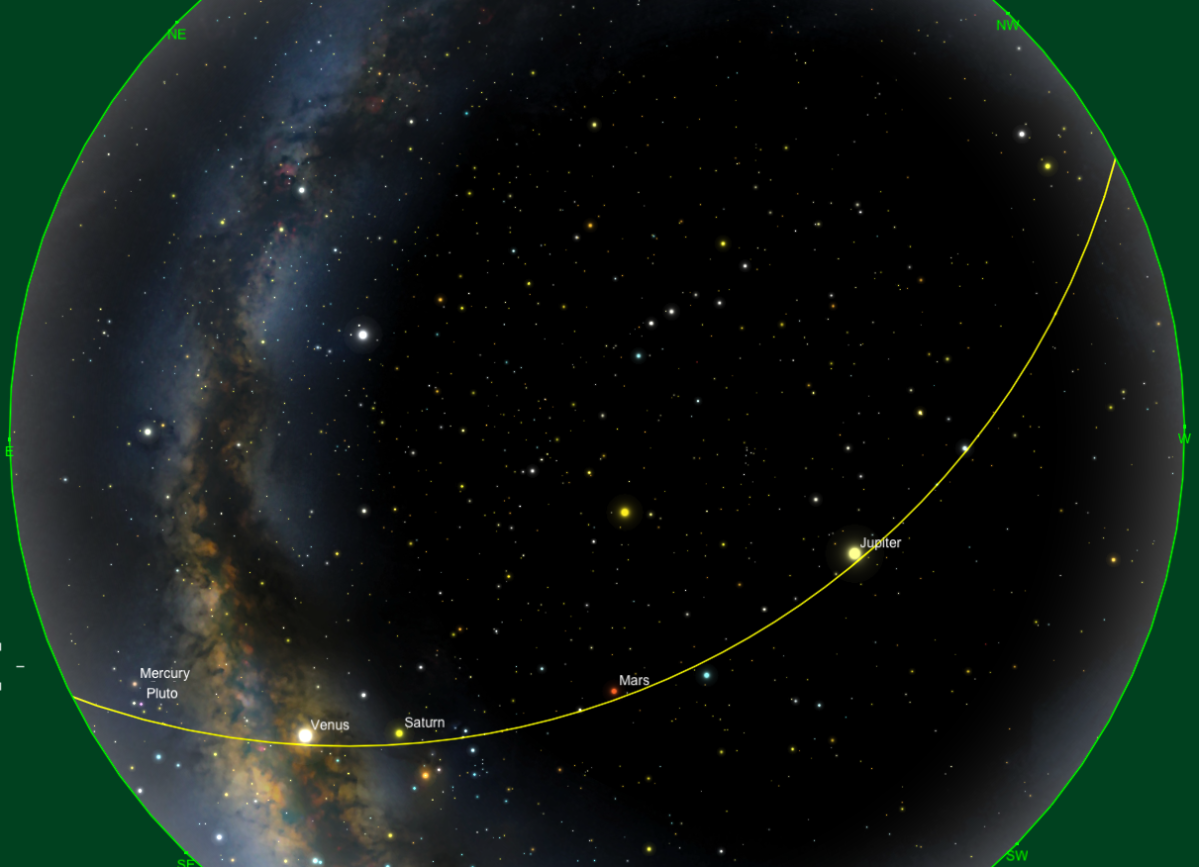

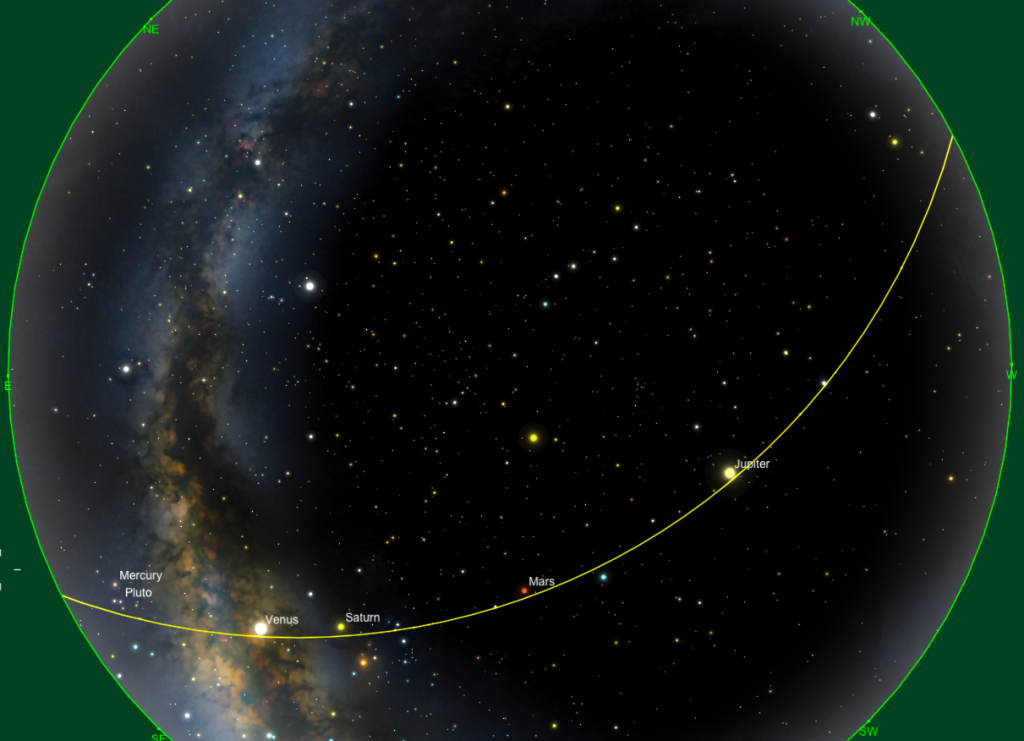

This year’s transit will be widely visible from most of Earth, including the Americas, the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, New Zealand, Europe, Africa, and western Asia. It starts at about 6:35 a.m. CST, but viewers in some areas, such as the West Coast, will have to wait until the Sun rises at their location to see the transit already in progress. Thankfully, this transit will last almost six hours, so there will be plenty of time to catch the show. At about 9:20 a.m. CST, Mercury’s center will be as close as it is going to get to the Sun’s.

Mercury’s tiny disk, jet black and perfectly round, covers a tiny fraction of the Sun’s blinding surface — only 1/283 of the Sun’s apparent diameter. So you’ll need the magnification of a telescope (minimum of 50x) with a solar filter to view the transit. Never look at the Sun directly or through a telescope without proper protection. It can lead to serious and permanent vision damage. Always use a safe Sun filter to protect your eyes!

Scientists have been using transits for hundreds of years to study the way planets and stars move in space. Edmund Halley used a transit of Venus in 1761 and 1769 to determine the absolute distance to the Sun. Another use of transits is the dimming of Sun or star light as a planet crosses in front of it. This technique is one way planets circling other stars can be found. Scientists can measure brightness dips from these other stars (or from the Sun) to calculate sizes of planets, how far away the planets are from their stars, and even get hints of what they’re made of.