By Wayne Smith

From a total solar eclipse in April to a partial lunar eclipse of September’s Harvest Moon, 2024 has been sweet for skywatchers – professionals and amateurs alike. And just in time for Halloween, stargazers can anticipate another treat in the pre-dawn hours of Oct. 20 and 21 thanks to the Orionids Meteor Showers. That is unless the Moon or cloudy skies don’t provide too many tricks.

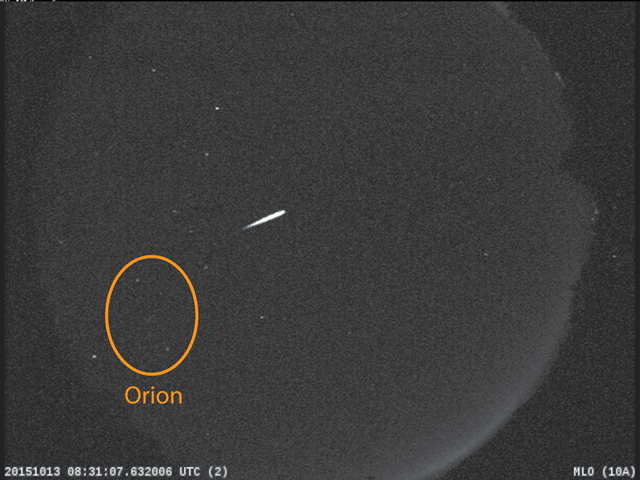

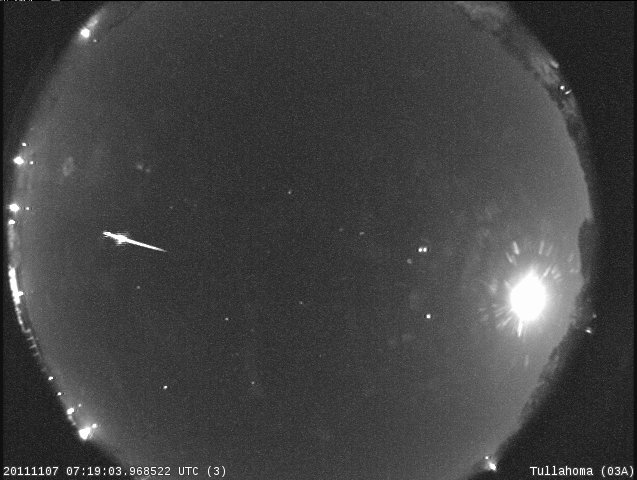

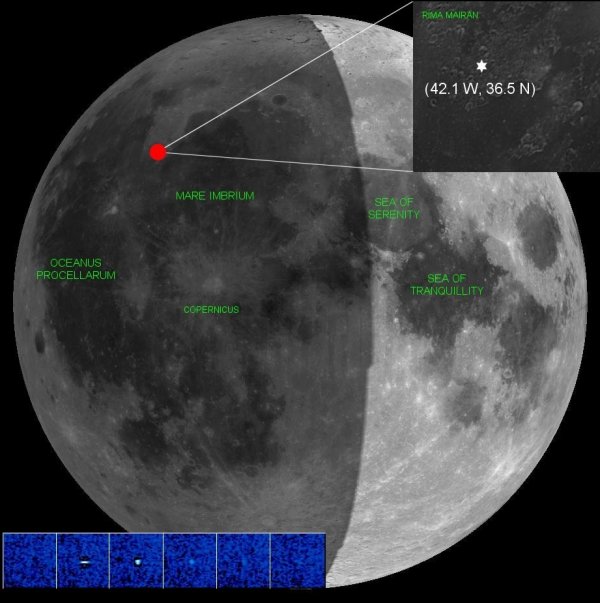

The Orionids, which peak during mid-October each year, are considered to be one of the most beautiful meteor showers of the year. Orionid meteors are known for their brightness and for their speed. Of course, the ability to see them will depend on clear evening skies. And a bright waning gibbous Moon – where it moves between full and last quarter phases – will outshine fainter meteors, greatly reducing the number of meteors visible to skywatchers.

Still, a few Orionids should hopefully be viewable in both the Northern and Southern Hemispheres during the hours after midnight through before dawn on the mornings of Sunday, Oct. 20, and Monday, Oct. 21.

The Orionids are also framed by some of the brightest stars in the night sky, which lend a spectacular backdrop for these showy meteors.

“Find an area well away from the city or street lights,” said Bill Cooke, who leads NASA’s Meteoroid Environment Office at the agency’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. “Come prepared with a blanket. Lie flat on your back and look up, taking in as much of the sky as possible. In less than 30 minutes in the dark, your eyes will adapt and you will begin to see meteors.”

Aside from potentially producing spectacular fireballs, the Orionids reflect quite a legacy. Their parent comet is the most famous one of them all – Halley’s Comet. Each time that Halley returns to the inner solar system its nucleus sheds ice and rocky dust into space. These dust grains eventually become the Orionids in October and the Eta Aquarids in May if they collide with Earth’s atmosphere.

Comet Halley takes about 76 years to orbit the Sun once. The last time comet Halley was seen by casual observers was in 1986 and it will not enter the inner solar system again until 2061. The comet is named for Edmond Halley, who discovered in 1705 that three previous comets seemed to return every 76 years or so and suggested that these sightings were in fact all the same comet. The comet returned as he predicted, and so it was named in Halley’s honor.

So, while it’ll take another 37 years to see Halley’s Comet, the Orionids offer a glimpse of its past.

The Orionids start winding down what has been an eventful calendar year for skywatching events. There was the total solar eclipse across most of North America on April 8 – the alignment of the Sun, Moon, and Earth – creating a total solar eclipse lasting 4 minutes and 12 seconds. The Perseids brought nightsky fireworks in August. And the partial lunar eclipse of a full supermoon – the Harvest Moon – welcomed fall and provided some spectacular images. Other skywatching events for 2024 include the Geminid and Ursid meteor showers in December.

Read more about meteors here.

Lane Figueroa

Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville, Ala.

256.544.0034

lane.e.figueroa@nasa.gov