In today’s A Lab Aloft, guest blogger Liz Warren, Ph.D., looks at the differences between male and female astronaut physiology on long duration space missions.

I hate to break it to you, but men are not actually from Mars and women are not really from Venus. This silly saying illustrates a question that researchers, however, are serious about studying. With International Women’s Day around the corner, I thought it the ideal time to address the question: Is there a difference between the sexes as the human body adapts to microgravity?

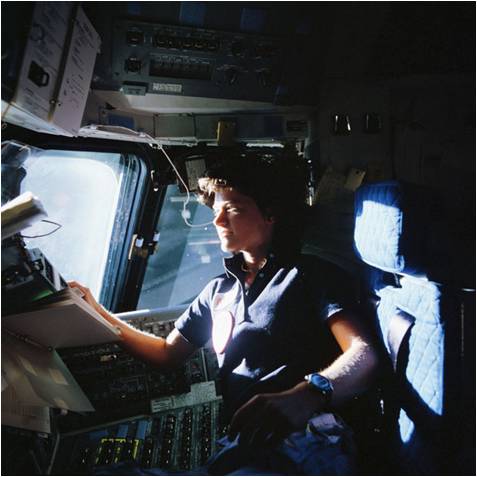

You may remember reading the earlier blog that I wrote about celebrating “firsts” for women space explorers. The sky is certainly no longer the limit for females interested in exploration, science or any other career they wish to pursue. In fact, if you’re following our current mission, you already know we have two women living and working on the International Space Station.

In the fall of 2015, Sarah Brightman will be the 60th woman to fly in space. As we approach longer durations in human spaceflight, such as the one-year mission and the journey to Mars, it is important to tease out all aspects of how humans handle life in microgravity to ensure crew safety. The answers may also hold insights for human health even if you never leave the ground.

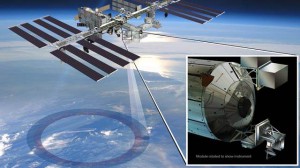

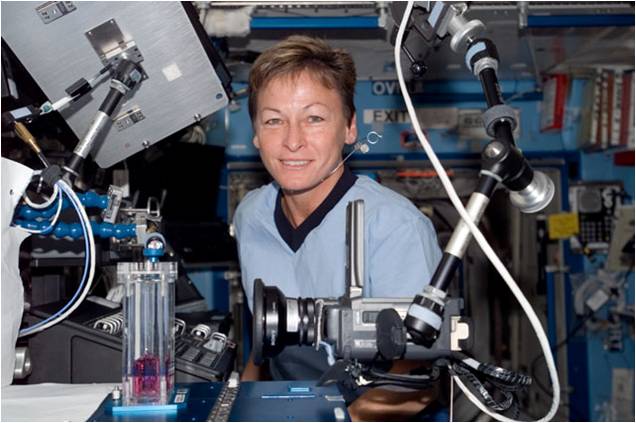

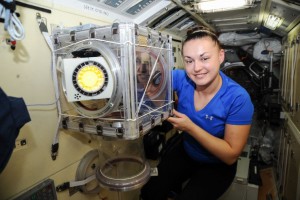

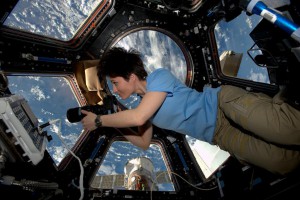

Our current crew aboard the space station includes ESA (European Space Agency) astronaut of Italian nationality, Samantha Cristoforetti, and a Roscosmos cosmonaut of Russian nationality, Yelena Serova. While serving aboard the orbiting laboratory for about six months, they each perform experiments in disciplines that range from technology development, physical sciences, human research, biology and biotechnology to Earth observations. This research helps in benefitting our lives here on Earth and enables future space exploration. They also engage students through educational activities in addition to operational tasks such as equipment maintenance and visiting vehicle tasks.

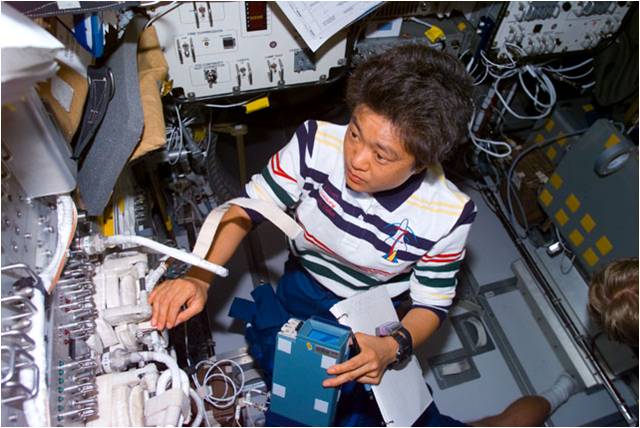

It’s important to acknowledge the contributions women in space make to both exploration and research. For instance, on Feb. 3, a prestigious tribute went to another woman space explorer, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) astronaut Chiaki Mukai. She was conferred the National Order of the Legion of Honour, Chevalier. Mukai flew aboard space shuttle missions STS-65 and STS-95, and is currently the director of the JAXA Center for Applied Space Medicine and Human Research (J-CASMHR). The work these trailblazers accomplish also includes their role as research subjects themselves.

Female space explorers are skilled professionals, representing the best humanity has to offer, executing complex tasks in an unforgiving environment. Their sex differentiates them only so far as biology determines—which is exactly the topic covered in a recent compendium titled “Impact of Sex and Gender on Adaptation to Space.” The results were published in the November 2014 issue of the Journal of Women’s Health.

Space exploration is inherently dangerous, and as we look to longer duration spaceflights to Mars and beyond, NASA wants to make sure we are addressing the right questions to minimize risk to our astronaut crews. Based on a recommendation by the National Academy of Sciences, NASA and the National Space Biomedical Research Institute (NSBRI) assembled six scientific working groups to compile and summarize the current body of knowledge about the different ways that spaceflight affects the bodies of men and women. The groups focused on cardiovascular, immunological, sensorimotor, musculoskeletal, reproductive and behavioral implications on spaceflight adaptation for men and women. NASA and NSBRI created a diagram summarizing differences between men and women in cardiovascular, immunologic, sensorimotor, musculoskeletal, and behavioral adaptations to human spaceflight.

Thus far, the differences between the male and female adaptation to spaceflight are not significant. In other words, mission managers planning a trip to Mars, for example, can do so without consideration of the sex of the crew members. However, many questions remain unanswered and require further studies and more women subjects in the human-health investigations. There is an imbalance in data available for men and women, primarily due to fewer women having flown in space.

As a physiologist, I am intrigued by several of the differences described in the journal. An area that interests me in particular is cardiovascular physiology. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, cardiovascular disease—including heart disease, stroke and high blood pressure—is the number one killer of men and women across America. Many studies have shown that healthy habits including good nutrition and exercise are important for maintaining a healthy heart here on Earth. Those habits are even more important for astronauts on the space station.

Of the findings described in the journal, one is that women astronauts tend to suffer more orthostatic intolerance upon standing after return to Earth. Related to this finding, women also appear to lose more blood plasma during spaceflight. Possibly connected to the inherent differences in the cardiovascular system between men and women, male astronauts appear to suffer more vision impairment issues in space than women, although the difference is not statistically significant due to the small number of subjects—meaning more research needs to be done.

Another difference between men and women in spaceflight is worth noting, and that is the radiation standard. While the level of risk allowed for both men and women in space is the same, women have a lower threshold for space radiation exposure than men, according to our models.

This is an exciting time in human space exploration. We are addressing questions today that will lead to safer journeys off our planet. This month, NASA astronaut Scott Kelly and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko will embark on the first joint U.S.-Russian one-year mission to the space station. Most stays on station are six months in duration, but planners anticipate a journey to Mars to be closer to 1,000 days. This first one-year mission is a stepping stone in our travels beyond low-Earth orbit. NASA anticipates to continue one-year long missions, and women will be part of these crew selections.

In the meantime, what we learn about our bodies off the Earth has benefits for the Earth. In part one of this guest blog, I stated that, “in space exploration and in science, we stand on the shoulders of those who came before us.” I am thrilled to think of what we are about to learn from the one-year mission, as well as the continued research on and by both men and women in orbit. What an exciting time for humanity!

Liz Warren, Ph.D., is a physiologist with Barrios Technology, a NASA contractor supporting the International Space Station Program Science Office. Warren has a doctorate in molecular, cellular, and integrative physiology from the University of California at Davis, completed post-doctoral fellowships in molecular and cell biology and neuroscience, and has authored publications ranging from artificial gravity protocols to neuroscience to energy balance and metabolism.