Camelopardalis.

Camelopardalis.

It’s a strange-sounding name for a constellation, coming from the Greco-Roman word for giraffe, or “camel leopard”. The October Camelopardalids are a collection of faint stars that have no mythology associated with them — in fact, they didn’t begin to appear on star charts until the 17th century.

Even experienced amateur astronomers are hard-pressed to find the constellation in the night sky. But in early October, it comes to prominence in the minds of meteor scientists as they wrestle with the mystery of this shower of meteors, which appears to radiate from the giraffe’s innards.

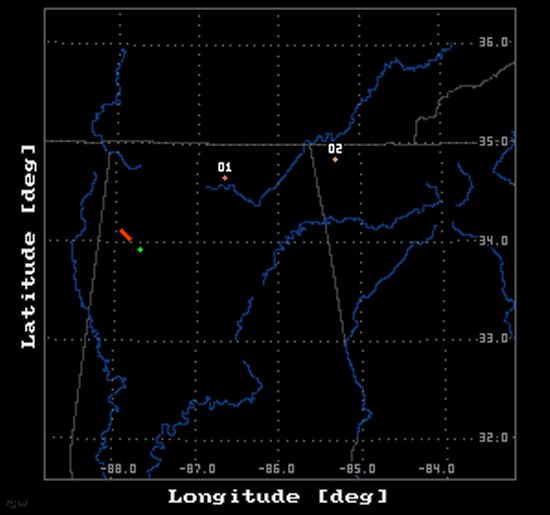

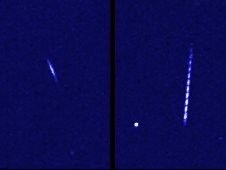

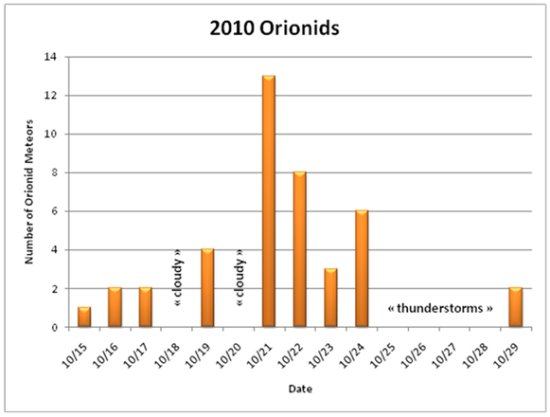

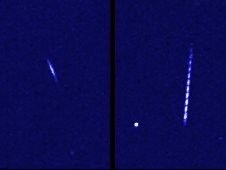

The October Camelopardalids are not terribly spectacular, with only a handful of bright meteors seen on the night of Oct. 5. It may have been first noticed back in 1902, but definite confirmation had to wait until Oct. 2005, when meteor cameras videotaped 12 meteors belonging to the shower. Moving at a speed of 105,000 miles per hour, Camelopardalids ablate, or burn up, somewhere around 61 miles altitude, according to observations from the NASA allsky meteor cameras on the night of Oct. 5, 2010.

So they aren’t spectacular. Their speed is calculated. Their “burn up” altitudes and orbits are known. So what’s the mystery?

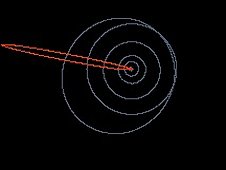

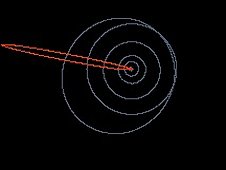

Camelopardalids have orbits, which indicates that they come from a long period comet, like Halley’s Comet. But the Camelopardalids don’t come from Halley, nor from any of the other comets that have been discovered. Hence the mystery: somewhere out there is — or was — a comet that passes close to Earth which has eluded detection. These tiny, millimeter size bits of ice leaving pale streaks of light in the heavens are our only clues about a comet of a mile, maybe more, in diameter.

Camelopardalids have orbits, which indicates that they come from a long period comet, like Halley’s Comet. But the Camelopardalids don’t come from Halley, nor from any of the other comets that have been discovered. Hence the mystery: somewhere out there is — or was — a comet that passes close to Earth which has eluded detection. These tiny, millimeter size bits of ice leaving pale streaks of light in the heavens are our only clues about a comet of a mile, maybe more, in diameter.

This is why astronomers keep looking at the Camelopardalids meteors. They hope that measuring more orbits may eventually help determine the orbit of the comet, enabling us to finally locate and track this shadowy visitor to Earth’s neighborhood.

Camelopardalis.

Camelopardalis.

Camelopardalids have orbits, which indicates that they come from a long period comet, like Halley’s Comet. But the Camelopardalids don’t come from Halley, nor from any of the other comets that have been discovered. Hence the mystery: somewhere out there is — or was — a comet that passes close to Earth which has eluded detection. These tiny, millimeter size bits of ice leaving pale streaks of light in the heavens are our only clues about a comet of a mile, maybe more, in diameter.

Camelopardalids have orbits, which indicates that they come from a long period comet, like Halley’s Comet. But the Camelopardalids don’t come from Halley, nor from any of the other comets that have been discovered. Hence the mystery: somewhere out there is — or was — a comet that passes close to Earth which has eluded detection. These tiny, millimeter size bits of ice leaving pale streaks of light in the heavens are our only clues about a comet of a mile, maybe more, in diameter.