A bright fireball lit up skies over Michigan at 8:08 p.m. EST on Jan. 16, an event that was witnessed and reported by hundreds of observers, many who captured video of the bright flash.

Based on the latest data, the extremely bright streak of light in the sky was caused by a six-foot-wide space rock — a small asteroid. It entered Earth’s atmosphere somewhere over southeast Michigan at an estimated 36,000 mph and exploded in the sky with the force of about 10 tons of TNT. The blast wave felt at ground level was equivalent to a 2.0 magnitude earthquake.

The fireball was so bright that it was seen through clouds by our meteor camera located at Oberlin college in Ohio, about 120 miles away.

Events this size aren’t much of a concern. For comparison, the blast caused by an asteroid estimated to be around 65 feet across entering over Chelyabinsk, Russia, was equivalent to an explosion of about 500,000 tons of TNT and shattered windows in six towns and cities in 2013. Meteorites produced by fireballs like this have been known to damage house roofs and cars, but there has never been an instance of someone being killed by a falling meteorite in recorded history.

The Earth intercepts around 100 tons of meteoritic material each day, the vast majority are tiny particles a millimeter in diameter or smaller. These particles produce meteors are that are too faint to be seen in the daylight and often go unnoticed at night. Events like the one over Michigan are caused by a much rarer, meter-sized object. About 10 of these are seen over North America per year, and they often produce meteorites.

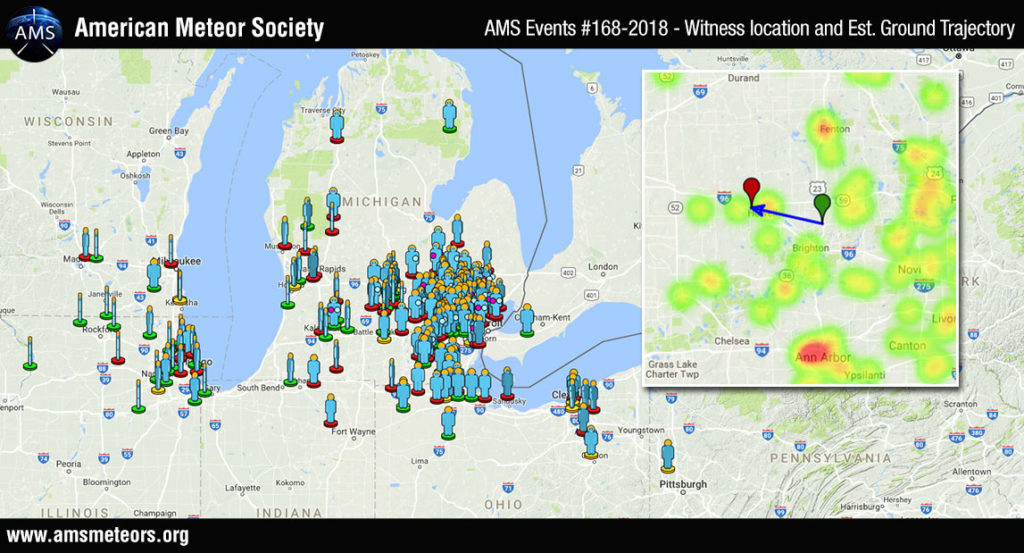

There are more than 400 eyewitness reports of the Jan. 16 meteor, primarily coming from Michigan. Reports also came from people in nearby states and Ontario, Canada, according to the American Meteor Society. Based on these accounts, we know that the fireball started about 60 miles above Highway 23 north of Brighton and travelled a little north of west towards Howell, breaking apart at an altitude of 15 miles. Doppler weather radar picked up the fragments as they fell through the lower parts of the atmosphere, landing in the fields between the township of Hamburg and Lakeland. One of the unusual things about this meteor is that it followed a nearly straight-down trajectory, with the entry angle being just 21 degrees off vertical. Normally, meteors follow a much more shallow trajectory and have a longer ground track as a result.

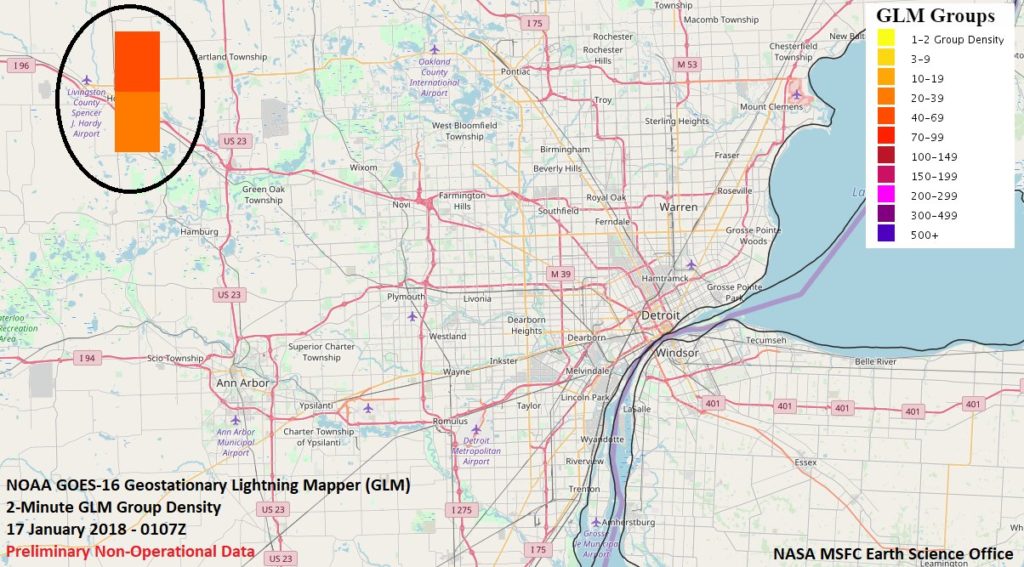

NASA’s Short-term Prediction Research and Transition Center reported that a space-based lightning detector called the Geostationary Lightning Mapper — “GLM” for short — observed the bright meteor from its location approximately 22,300 miles above Earth. The SPoRT team helps organizations like the National Weather Service use unique Earth observations to improve short-term forecasts.

GLM is an instrument on NOAA’s GOES-16 spacecraft, one of the nation’s most advanced geostationary weather satellites. Geostationary satellites circle Earth at the same speed our planet is turning, which lets them stay in a fixed position in the sky. In fact, GOES is short for Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite. GLM detected the bright light from the fireball and located its exact position within minutes. The timely data quickly backed-up eyewitness reports, seismic data, Doppler radar, and infrasound detections of this event.

Much like the nation’s weather satellites help us make decisions that protect people and property on Earth, NASA’s Meteoroid Environment Office watches the skies to understand the meteoroid environment and the risks it poses to astronauts and spacecraft, which do not have the protection of Earth’s atmosphere. We also keep an eye out for bright meteors, so that we can help people understand that “bright light in the night sky.”