The Orionid meteor shower is over, as Earth has finally left the wide stream of debris produced by Comet Halley. However, we are now encountering particles produced by Comet Encke, the second comet to be assigned a name (Halley was the first). This debris wake is much larger, lasting many weeks, causing the Taurid complex of meteor showers — the South Taurids, which peak on October 10, and the North Taurids, which peak on November 12. Rates are low, only about 5 per hour, so why the interest?

1) Comet Encke is thought by some astronomers to be a piece of a larger comet that broke up 20,000 to 30,000 years ago. These comet break-ups are often caused by gravitational encounters with Earth or other planets — Jupiter especially is a bit of a Solar System bully. This break-up may explain why there are so many Encke-like pieces moving around the inner Solar System, some of them pretty big. One astronomer has even postulated that it was a huge fragment of Comet Encke’s parent that produced a 10 megaton explosion over Siberia back in 1908.

2) Taurid meteors tend to be larger than the norm, which means they are bright, many being fireballs. They also penetrate deeper into Earth’s atmosphere than many other shower meteors. For example, Orionids typically burn up at altitudes of 58 miles, whereas Taurids make it down to 42 miles. Some can get even lower — on the night of November 6, our meteor cameras tracked two 1-inch North Taurid meteors, both getting down to an altitude of of 36 miles.

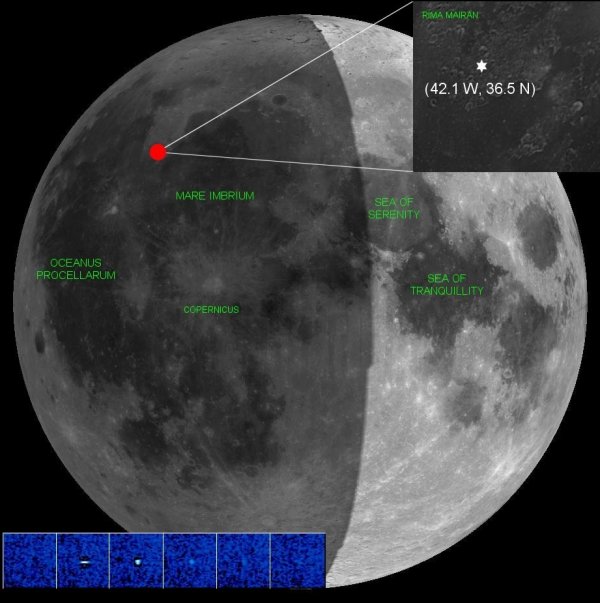

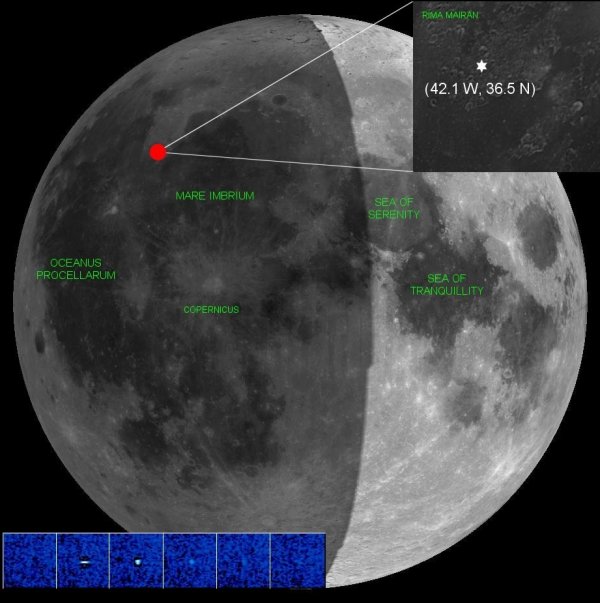

3) Because they are big and possess a goodly amount of energy (imagine a 1 inch hunk of ice moving at 63,000 mph — 29 times faster than a bullet from an M-16 rifle), they produce decent quantities of light when they strike the surface of the Moon. This makes Taurid lunar impacts easy to see with Earth-based telescopes; in fact, the first lunar meteoroid impact observed by NASA was a Taurid back on November 7th of 2005, and we detected it with a 10″ telescope of the same type used by amateurs all over the world!

So when you are out at night this month, look up and watch for the occasional fireball – it’ll probably be a Taurid!

P.S. Check out the last couple weeks of meteors seen on fireballs.ndc.nasa.gov and you will notice there are several fireballs that are associated with the Northern or Southern Taurids (NTA or STA). Don’t even have to go outside!

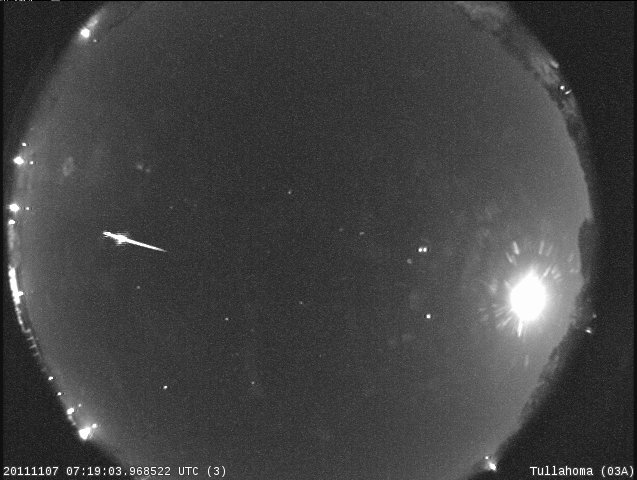

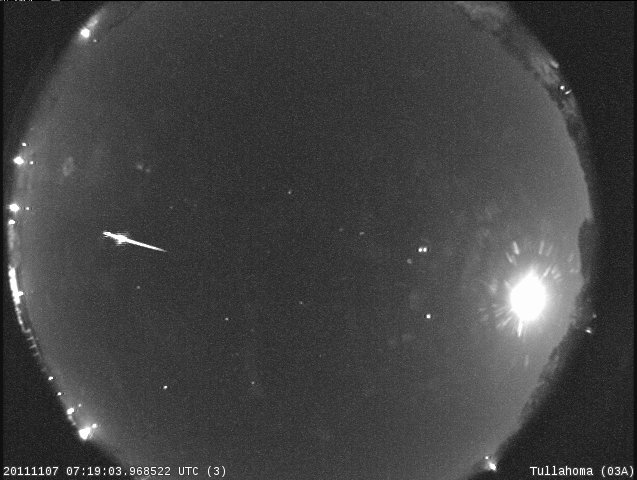

A bright Taurid streaks across the southern Tennessee sky in this image taken by a NASA meteor camera in the wee hours of November 7, 2011.

The same Taurid; the bright flare in the meteor about two-thirds of the way into the video is caused by the meteor breaking into smaller pieces. When this happens, energy is released, resulting in a flash of light.

This graphic shows the location of the first lunar meteoroid impact observed by NASA on November 7, 2005. Originating from Comet Encke, it was a Taurid meteoroid striking the Moon’s surface with a speed of about 63,000 mph. The sequence of false color images at the lower left shows the impact flash as it evolved over consecutive video frames (1/30th second intervals).