It’s almost time!

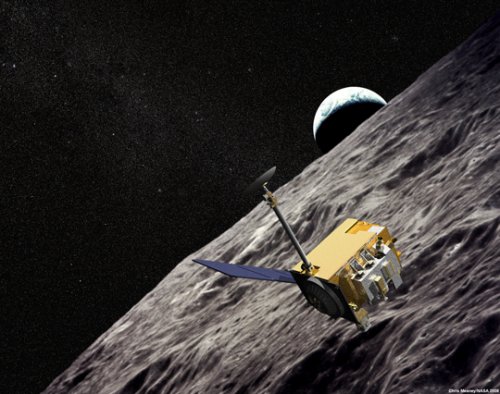

It’s been over three months since the Atlas V soared from Cape Canaveral, Fla. into space carrying the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (“LCROSS” for short). Now it’s finally time for LCROSS to do its things and get up close and personal with the moon.

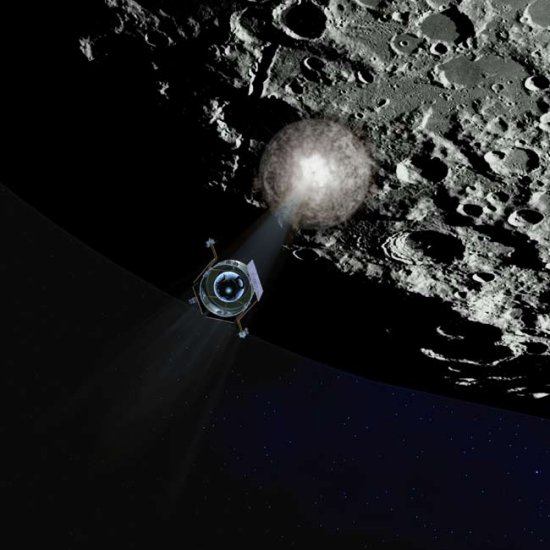

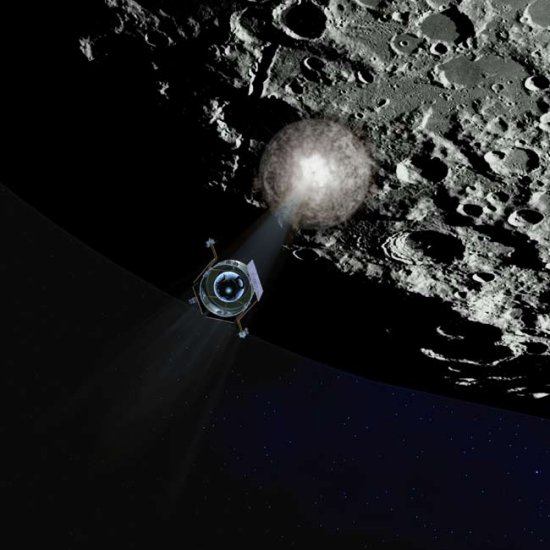

An artist’s interpretation of NASA’s LCROSS spacecraft observing the first

impact of its rocket booster’s Centaur upper stage before heading in for its

own crash into the moon’s south pole. Credit: NASA

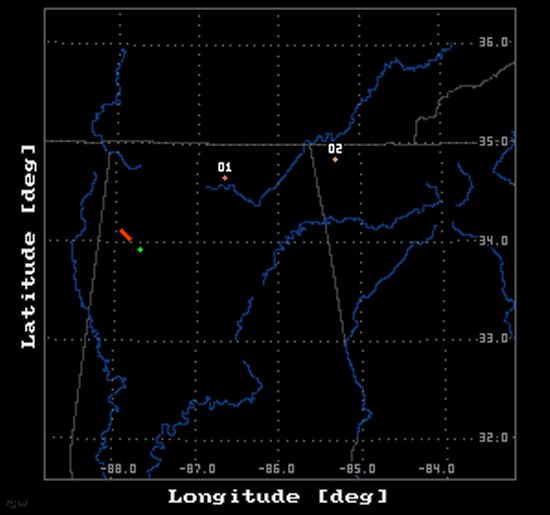

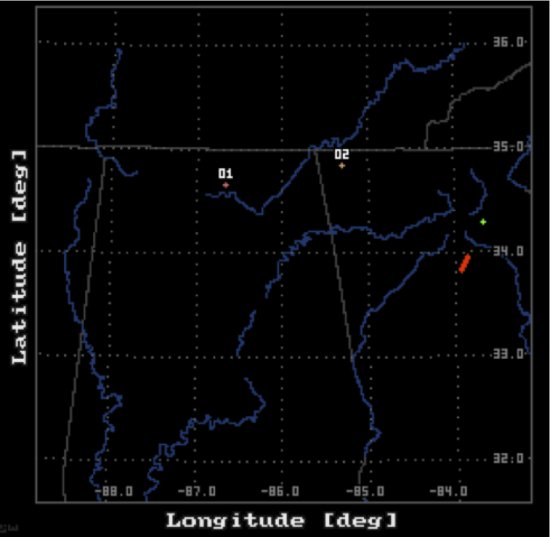

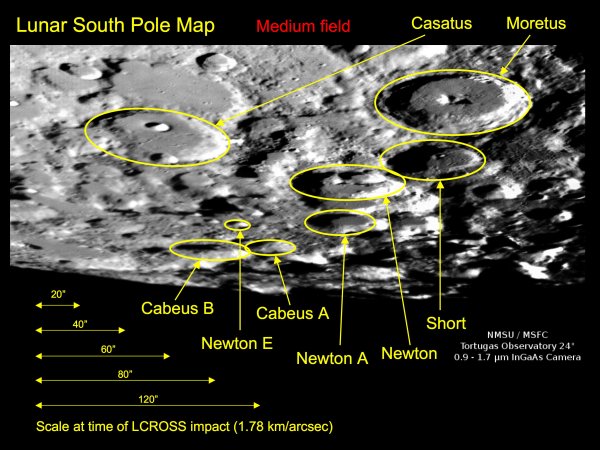

On Oct. 9 beginning at 6:30 a.m. CDT, the LCROSS spacecraft and heavier Centaur upper stage rocket will execute a series of procedures to separately hurl themselves toward the lunar surface to create a pair of debris plumes that will be analyzed for the presence of water ice. The Centaur is aiming for the Cabeus crater near the moon’s south pole and scientist expect it to kick up approximately ten kilometers (6.2 miles) of lunar dirt from the crater’s floor.

Image of NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility. Credit: NASA

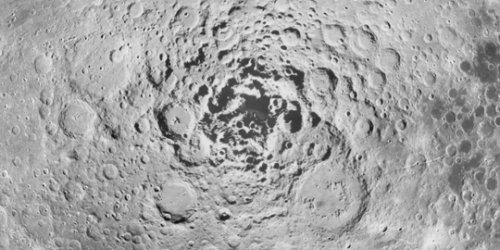

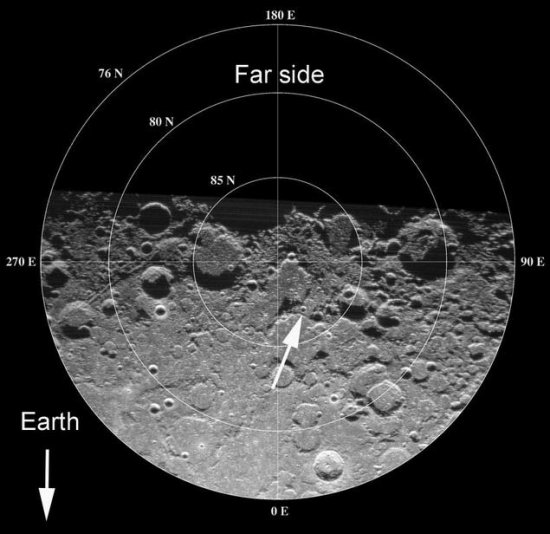

The sun never rises above certain crater rims at the lunar pole and some crater floors may not have seen sunlight for billions of years. With temperature estimated to be near minus 328 degrees Fahrenheit, these craters can ‘cold trap’ or capture most volatiles or water ice.

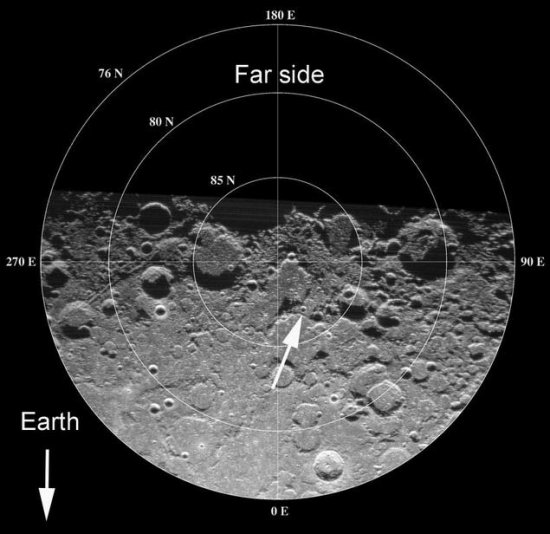

Earth-based radar image of the North Pole of the Moon, showing the position of the crater

Erlanger (arrow). Photo: Arecibo Observatory and NASA

On the day of impact, LCROSS at approximately 40,000 kilometers (25,000 miles) above the lunar surface will spin 180 degrees to turn its science payload toward the moon and fire thrusters to slow down. The spacecraft will observe the flash from the Centaur’s impact and fly through the debris plume. Data will be collected and streamed to LCROSS mission operations for analysis. Four minutes later, LCROSS also will impact, creating a second debris plume.

The LCROSS science team will lead a coordinated observation campaign that includes LRO, the Hubble Space Telescope, observatories on Hawaii’s Mauna Kea and amateur astronomers around the world.

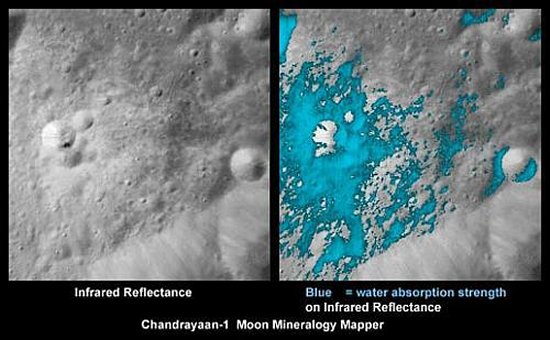

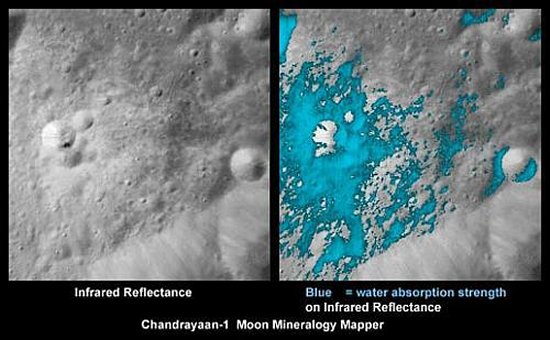

It’s an exciting time for the most prominent object in our night sky with water being found on the surface last week by NASA’s Moon Mineralogy Mapper — one of eleven scientific devices carried by the Chandrayaan-One spacecraft of the Indian Space Research Organization.

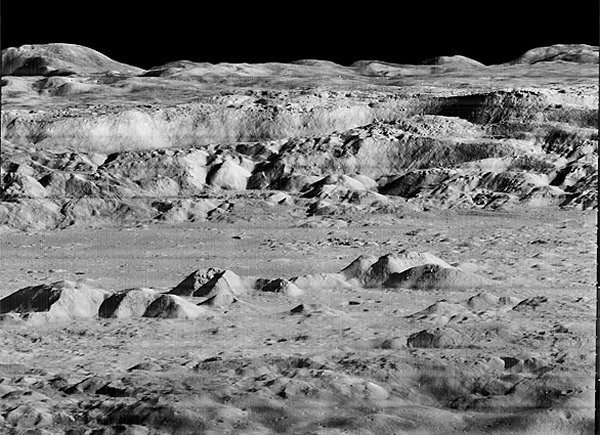

These images show a very young lunar crater on the side of the moon that faces away

from Earth, as viewed by NASA’s Moon Mineralogy Mapper on the Indian Space

Research Organization’s Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft. Image credit: NASA

However, the Moon Mineralogy Mapper can only observe lunar soil to a depth of a few millimeters and the amount of water present in that layer is very small. It’s been said the driest deserts on Earth have more water than the surface of the moon near its poles. LCROSS could prove that water does exist deeper beneath the moon’s surface and present a valuable resource in the human quest to explore the solar system.

Astronaut James Irwin, lunar module pilot, gives a military salute while standing

beside the deployed U.S. flag during the Apollo 15 lunar surface extravehicular

activity (EVA) at the Hadley-Apennine landing site. Credit: NASA

Two ways to watch the impact:

Tune into NASA TV. The Agency will broadcast impact live from the moon, with coverage beginning Friday morning at 5:15 a.m. CDT. The first hour, pre-impact, will offer expert commentary, spacecraft status reports, and a computer-generated preview of the impacts.

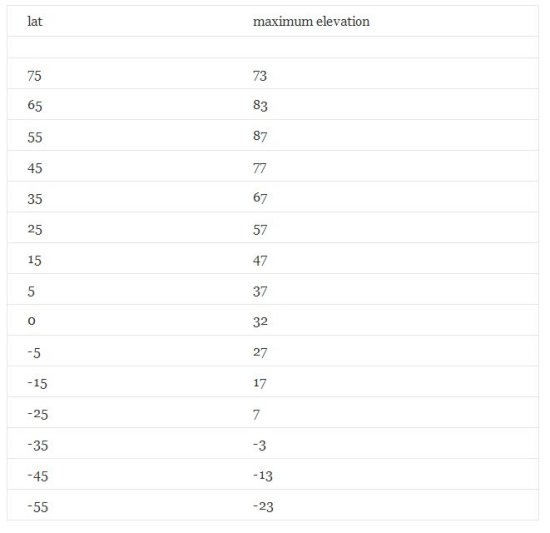

Or you can watch in your backyard using your telescope. Viewing opportunities are best for the Pacific Ocean and western parts of North America due to absence of light and a good view of the Moon at the time of impact. Hawaii is the best place to be, with Pacific coast states of the USA a close second. Any place west of the Mississippi River, however, is a potential observing site.

W.M. Keck Observatory and the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility with Haleakala on

Maui in the distance as seen at sunset from Mauna Kea. Credit: John Fischer