The first-ever Camelopardalid meteor shower peaked in the wee hours of Saturday, May 24, offering stargazers a rare sight — the debut meteor display from the dusty Comet 209P/LINEAR. Below is video footage of a Camelopardalid meteor recorded by our NASA camera at Allegheny Observatory near Pittsburg, PA at 11:22 PM EDT on May 24. Still images of Camelopardalids are available in our Flickr gallery.

Month: May 2014

Getting Ready For Camelopardalids!

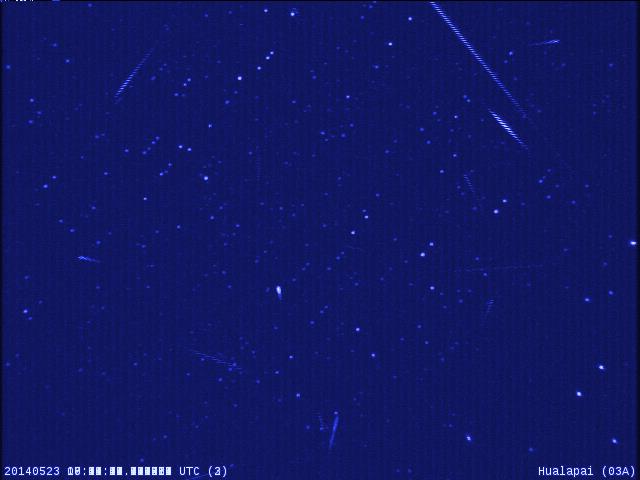

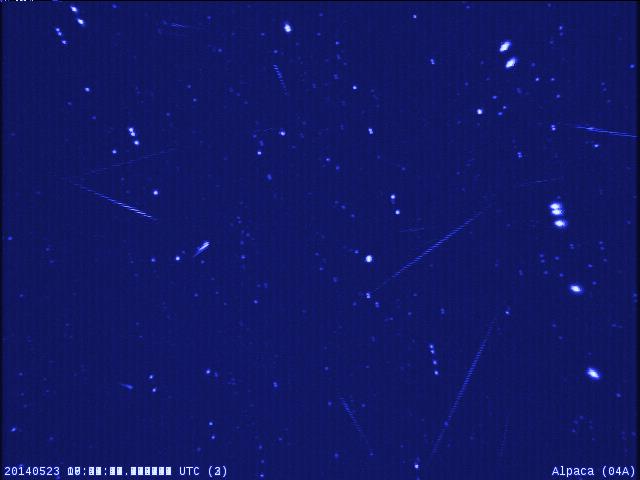

Part of our team of experts is in Kingman, Arizona, getting ready for the highly anticipated May Camelopardalid meteor shower tonight. They sent back some black & white and false color (blue) meteor image composites from two NASA meteor cameras deployed to Arizona for this meteor shower. This first night of observational results comes before the expected May Camelopardalid activity. Meteors shown therefore do not belong to that shower, but were observed on 5/23/2014 UTC.

Camera Location # meteors in image

03 Hualapai Valley Observatory, Kingman, AZ 20

04 Alpacas of the Southwest, Kingman, AZ 16

Twelve meteors were common to both cameras, allowing for meteor trajectory calculations.

They also sent this picture to show us that even the alpacas are excited and ready to assist our experts tonight!

Left to Right – Chris Hozian, Aaron Kingery, Danielle Moser, Herschel, Ted, and Rhiannon Blaauw

Frequently Asked Questions About the Camelopardalid Meteor Shower

As the date of the possible new May Camelopardalid meteor shower looms, we wanted to offer some answers to frequently asked questions. We hope this question and answer post will be helpful as you observe the shower.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How do you pronounce the name of this meteor shower?

A: Ask a different person and you’ll get a different answer! Common pronunciations are camel-oh-PAR-dahl-idz, kah-MEL-oh-PAR-dal-idz, and camel-oh-par-DAL-idz. It it’s too much of a tongue twister, you are camelopardon-ed. 🙂

Q: Why does this shower have such a funny name?

A: Meteor showers are named after the location of their radiant – or the point in the sky from which the meteors appear to originate. This shower is expected to produce meteors in May with a radiant in the constellation Camelopardalis.

Q: Can I see the May Camelopardalids from my location in _____?

A: Check out the visibility map below. If your location is in the yellow zone, and you have clear dark skies, you should be able to see May Camelopardalids during the expected peak, if it occurs.

Q: When can I see May Camelopardalids?

A: The expected peak is between 1 and 3 am CDT on May 24.

Q: Where is the May Camelopardalid radiant?

A: The radiant is in the constellation Camelopardalis. It’s not a well-known constellation, but you can find the general direction if you look between Ursa Major and Cassiopeia.

Q: Should I look at the radiant to see May Camelopardalids?

A: Nope!

Q: Ok, where should I look then, smarty-pants?

A: If it’s not cloudy, get as far away from bright lights as you can, lie on your back, and look up. You should be able to see May Camelopardalids over the whole sky.

Q: How do I know if the meteor I just saw is a May Camelopardalid?

A: If you see a meteor, try to trace it’s path backwards. If you end up in the constellation Camelopardalis, there’s a good chance you’ve seen a May Camelopardalid!

Q: My skies are dark and cloud-free but I’m still not seeing any meteors! Why not?!

A: There are a couple of possibilities. (1) The comet wasn’t very active 200+ years ago, and therefore didn’t produce many meteoroids. So the meteor shower is much weaker than predicted. (2) You need to have patience. You also need to make sure your eyes are adapted to the dark – this takes about 45 minutes. Make sure you don’t keep looking at your phone or other sources of light, else your eyes will have to start the dark adaptation process all over again.

Q: Has a satellite ever been hit by a meteoroid?

A: Yes. Here are a few examples: Mariner IV, a NASA planetary exploration spacecraft encountered a meteoroid stream between the orbits of Earth and Mars in Sept 1967. The encounter damaged the thermal shield. Olympus, an ESA communication satellite, was struck by a Perseid near the time of the shower peak in August 1993. It was sent tumbling and exhausted its fuel supply.

Q: How big are May Camelopardalid meteoroids?

A: These meteoroids are expected to be anywhere from dust-grain sized to millimeter sized.

Q: How can a small bit of rock damage a satellite?

A: Meteoroids travel very fast and therefore have a lot of energy. The May Camelopardalids will be traveling slowly, as far as meteors go, but they will still be moving at 36,000 mph! That’s about 27 times faster than the Concorde jet!

You can get more facts about the May Camelopardalids here.

How do you say Camelopardalids? Find out here!

Watch our live feed of the shower: http://www.ustream.tv/channel/nasa-msfc

Join Us For the May Camelopardalids!

Step outside and take a look at the skies on the evening of May 23 into the early morning of May 24. Scientists are anticipating a new meteor shower, the May Camelopardalids. No one has seen it before, but the shower could put on a show that would rival the prolific Perseid meteor shower in August. The Camelopardalids shower would be dust resulting from a periodic comet, 209P/LINEAR.

“Some forecasters have predicted a meteor storm of more than 200 meteors per hour,” said Bill Cooke, lead for NASA’s Meteoroid Environment Office. “We have no idea what the comet was doing in the 1800s. The parent comet doesn’t appear to be very active now, so there could be a great show, or there could be little activity.”

The best time to look is during the hours between 06:00 and 08:00 Universal Time on May 24, or between 2-4 a.m. EDT. That’s when forecast models say Earth is most likely to encounter the comet’s debris. North Americans are favored because their peak occurs during nighttime hours while the radiant is high in the sky.

On the night of May 23-24, NASA meteor expert Bill Cooke will host a live web chat from 11 p.m. to 3 a.m. EDT. Go to this page to learn more about the May Camelopardalids, to get information about the live chat and to view the live Ustream view that will be available during the chat.

Earthgrazer Seen In The Southern Sky

Last night at 8:38:30 PM CDT, a basketball size meteoroid entered the atmosphere 63 miles above Columbia, South Carolina. Moving northwest at 78,000 miles per hour, it burned up 52 miles above the Tennessee country side, just north of Chattanooga. This fireball was not part of any meteor shower and belongs to a class of meteors called Earthgrazers. These meteors skim along the upper part of the atmosphere before burning up. This one travelled a distance of 290 miles, which is quite rare for a meteor.

Eta Aquarids Visible Tonight

There will still be Eta Aquarids visible tonight, but at a rate of less than half of last night’s peak. Those in the southern hemisphere will again see more Eta Aquarids than those in the northern hemisphere, but pretty much everywhere in the world except the Arctic Circle has a chance to view the shower. You can spot meteors any time after dark, but Eta Aquarids meteors will not be visible until after 2:30 AM local time, when the constellation of Aquarius rises above the horizon. The highest visibility for Eta Aquarids will be in the couple of hours before dawn, sometime after about 4:00 a.m. local time.

You don’t need special equipment like a telescope: you only need your eyes. If you have clear skies, go outside to a place away from city lights. Lie on your back and look straight up at the sky, allowing your eyes 30-45 minutes to adjust to the dark. Meteors may appear from any direction, and this gives you the widest possible field of view to spot one. On any given night, it’s possible to see 6-8 sporadic meteors per hour, even without a specific shower event.