At first, the geography of Antarctica might seem a little confusing. From space, much of Antarctica looks featureless and white, meaning there are few features to guide you. It’s one thing to know that Pine Island Glacier is in West Antarctica, but for some it might be unclear which part of the frozen continent is which. In the most general terms, Antarctica can be divided into three major areas: West Antarctica, East Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula.

The Antarctic Peninsula is probably Antarctica’s most prominent geographical feature and is home to scientific stations operated by the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Australia and other nations. This curved extension of the continent extends nearly 250 miles north of the Antarctic Circle and points toward the southern tip of South America. The Antarctic Peninsula has a number of glaciers and large floating ice shelves that are changing rapidly because this part of Antarctica is warming faster than the rest of the continent.

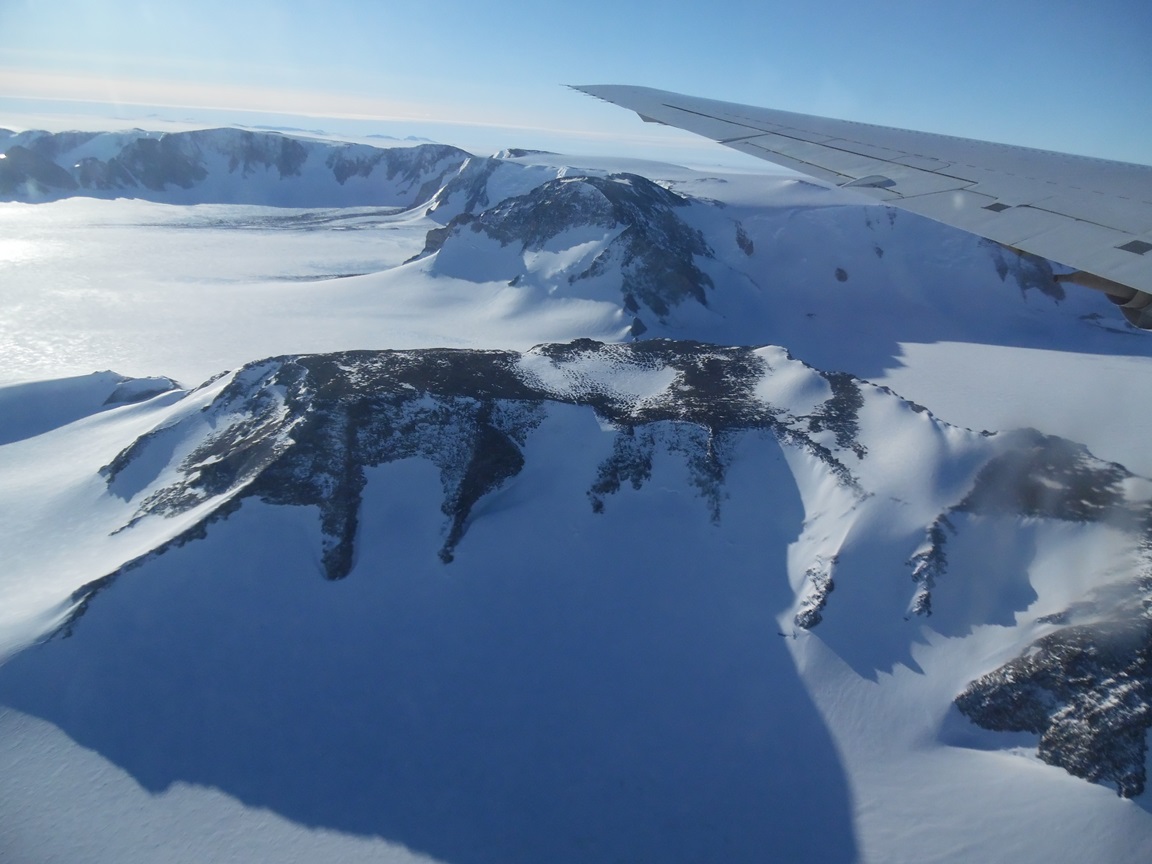

Running along the length of the peninsula, and extending across the continent is a mountain chain known as the Transantarctic Mountains. In addition to supplying spectacular views, the Transantarctics serve as a sort of dividing line across the continent, separating East and West Antarctica.

Although the Antarctic Ice Sheet is a continuous mass of ice, but it is sometimes helpful to think of it as two separate masses known as the West Antarctic and East Antarctic ice sheets, which are separated by the Transantarctics. Ice on the west side of this line flows west, while the opposite happens east of the divide.

East Antarctica is considerably larger than West Antarctica. The ice sheet covering East Antarctica is thick – nearly three miles (five kilometers) thick in some regions – and its surface is high and home to some of the coldest and driest condition on Earth.

The East Antarctic Ice Sheet is also considered more stable than the West Antarctic. One reason for this is the shape and elevation of bedrock beneath the ice. Heavy masses of ice push down on bedrock, depressing areas in the central part of the ice sheet below mean sea level. If those low-lying areas happen to be near the edge of the ice sheet, which is the case in large parts of West Antarctica, then ocean water can make its way under the ice, speeding up glacier flow.

This is one of the reasons that while both portions of the ice sheet are losing mass, West Antarctica is moving much faster. Recent studies of West Antarctica found that many of the large, fast-moving glaciers there are in an irreversible decline.

And while Antarctic land ice is shrinking, sea ice around the continent has been on the rise in recent years. Antarctica is surrounded on all sides by the Southern Ocean. During the winter, ocean water freezes, forming a layer of sea ice of roughly the same area as the Antarctic continent.

The ocean around Antarctica is divided into several seas. Starting to the right of the Antarctic Peninsula on the map above is the Weddell Sea, which extends to Cape Norvegia, a small point of land jutting off of East Antarctica. Moving clockwise we go around the East Antarctic coast all the way to the Ross Sea, south of New Zealand. Next comes the Amundsen Sea, which large West Antarctic glaciers like Pine Island and Thwaites drain into. And continuing on, we complete our trip around Antarctica, coming to the Bellingshausen Sea to the left of the Antarctic Peninsula.

For maps of Antarctica, including some that use imagery from the Landsat satellite, visit:

http://lima.usgs.gov/download.php

To use an interactive Antarctic atlas, visit:

http://lima.usgs.gov/antarctic_research_atlas

This entry originally appeared on the NASA Earth Observatory blog Notes from the Field.

http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/blogs/fromthefield/2014/11/19/east-and-west-the-geography-of-antarctica/