From: Lora Koenig, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Operation IceBridge Deputy Project Scientist

It arrived, finally it arrived! Yes, the new B200 windshield is here and currently being installed. You begin to realize how remote Kangerlussuaq, Greenland, is when you need something. In the United States you can overnight ship almost anything from Chicago style pizza to Memphis ribs to aircraft windows, but not here. Here, in Kangerlussuaq, the only way to get things this time of year is on one plane that arrives from Copenhagen, Denmark, Monday through Friday at 9:30 a.m. local time.

When the B200 windshield cracked on Monday the plane crew immediately ordered a new windshield to be sent from NASA Langley. It was shipped on Tuesday and arrived today. During the time that it took the windshield transit, the B200 plane crew took out the old windshield and prepped the plane for the new one.

I have learned a lot about aircraft windshields the past few days. For instance aircraft windshields are installed using a sealant (a glue to secure the windshield inside a bolted frame). Even though it has warmed up significantly since we first arrived, it’s just 27 F (-3 C) outside. That’s quite balmy compared to the -8 F (-22 C) temperatures of last week, but the windshield sealant needs temperatures around 77 F to cure. The aircraft is in a hanger but it is still too cold to cure quickly. The B200 crew spoke with some of the Air Greenland crew who lent us some Infrared (IR) heating lamps. The IR heating lamps will allow us to install the window and cut the curing time in half so we can get back in the air sooner.

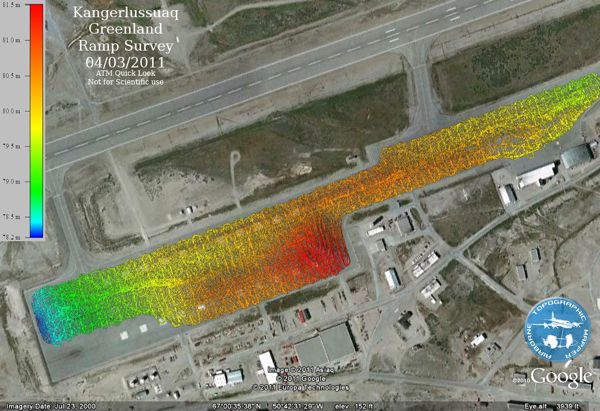

Right now the window is being installed and sealant applied. Overnight, the window will sit under the IR lamps. On Saturday the plane will undergo a test flight with only the pilots onboard to ensure the aircraft is safe. If all goes well by Monday we will be back up and flying the B200, which carries a high-altitude laser altimeter called the Land Vegetation and Ice Sensor (LVIS).

In the meantime the LVIS instrument has been resting but Elvis sightings around Greenland have remained high.

|

|

The first Elvis sighting was Rob White (left) from the B200 crew, and the second Elvis sighting was Shane Wake (right), an LVIS instrument operator.