By Jim Yungel, Airborne Topographic Mapper Program Manager, NASA Wallops Flight Facility

I thought I’d describe the facilities where the science team chooses to stay while here in Kangerlussuaq. One has the choice of staying in the airport hotel or in local lodging that is maintained for visiting scientists, the Kangerlussuaq International Science Support Center, or KISS.

KISS provides what can be called a dormitory for scientists, which is located in the former U.S. Air Force base. In the KISS dorm you get a room (generally two people to a room), and bed linens, common dorm bathrooms and washers/dryers down the hall. We do room cleaning ourselves, no services provided. There are two kitchens in the dorm, so we do a lot of cooking ourselves. Data processing is set up in one room downstairs.

Groceries are sold in a small store near the airport, and because the store is generally only open when we are airborne, one IceBridge team person (who runs our ground GPS unit) ends up shopping for many of us when we fly. Most of us cook meals either teaming up in groups or as individuals after we fly and following our nightly science meeting and weather briefing at 6 p.m. There is a small “mini-store” with expanded hours near the KISS facility where a limited selection of items is available.

Besides cooking in the dorms, there are three restaurant choices here in this small airport village.

First is the airport cafeteria, which is being renovated this year and has limited service. No hot breakfasts, cold buffet only, a few selections of hamburgers, chicken, fish and the like for lunch. Dinner generally is re-heated lunch choices.

Second is the nearby Thai grill known as the Polar Bear Inn. Yes, this village in Greenland has a Thai restaurant. They serve pizza, hamburgers, hot dogs, fried chicken, and a Thai menu. The pizza is good, and I personally like the Thai soups. There is seating for about 20 folks in a fast food environment.

Last is the Roklubben, or Row Club, a restaurant by a lake about three miles from town. It’s been a formal restaurant since we began visiting here regularly in the 1990s, but after the air force left, several folks tried to run it on and off over the years. About five years ago, the present owner, Chef Kim took it over. He is strict. You must be on time, and have exactly the number of people in the reservations (no walk-ins.) The Roklubben has a limited menu for just a few days of the week, and about once a week, Kim puts on a Greenlandic Buffet like the one our group attended. It’s expensive (about $80US/person with a drink), but worth it for the experience and trying different Greenlandic food.

Usually we’re here in Kangerlussuaq for three or four weeks. We generally have one buffet meal at the Roklubben as a group. I try to cook several meals for every meal I eat at the Thai restaurant, either cooking for myself or with a small group. We also have our annual Easter ham dinner for the whole NASA team and many of the local KISS folks each year.

Most of the science team enjoys staying in the KISS facility. We end up being more social than if we live in hotels and eat every night in restaurants. There are group viewings of movies (played from computers), we traditionally work on jigsaw puzzles in the common rooms, go on hikes, and cook together frequently. Several folks are musicians and play guitars, and there are always entertaining discussions going on in the hallways and rooms.

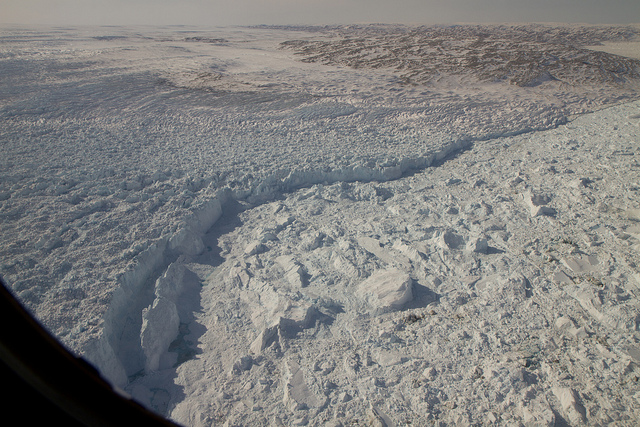

Above is an image mosaic from the Digital Mapping System aboard the NASA P-3 showing the terminus of the De Geer Glacier in east Greenland. The heavily crevassed end of the glacier is to the left of the image and large icebergs are to the right. Credit: NASA / DMS / Eric Fraim

Above is an image mosaic from the Digital Mapping System aboard the NASA P-3 showing the terminus of the De Geer Glacier in east Greenland. The heavily crevassed end of the glacier is to the left of the image and large icebergs are to the right. Credit: NASA / DMS / Eric Fraim