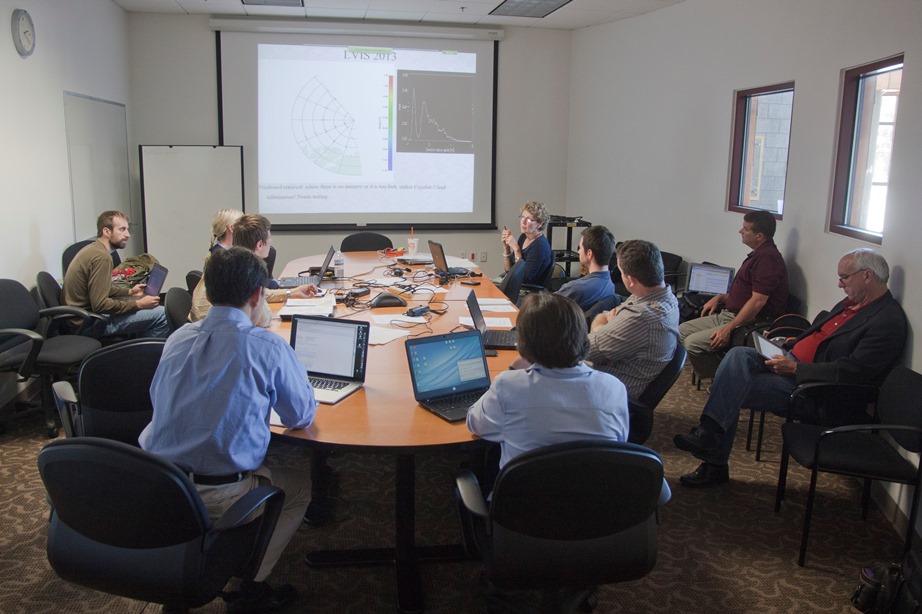

By Michal Segal Rosenheimer, Research Scientist, NASA Ames Research Center

Credit: NASA

The Spectrometer for Sky-Scanning, Sun-Tracking Atmospheric Research, or 4STAR, is an airborne instrument that measures aerosols (small particles suspended in the atmosphere), gases (ozone for example), and a variety of cloud properties. Currently it is being deployed on the NASA C-130 aircraft on its quest to measure aerosol and cloud properties in the Arctic, helping to answer some of the most difficult questions of climate change: what is the link between sea ice changes, clouds and global warming?

How does it work?

The 4STAR instrument has three different modes. The first of these, and the instrument’s main mode, is Sun-Tracking. This is where the instrument tracks the sun’s location in the sky, staring at it to measure the light transmitted from the sun to the instrument as it travels through the atmosphere. If the atmosphere is clean, we would measure the sun’s intensity. But because the atmosphere contains aerosols, gases and cirrus clouds, which are high, thin clouds made of ice crystals, we measure the amount of light that makes it through instead of being scattered and absorbed by these components of the atmosphere. By comparing measured light through the atmosphere to what we would have seen with no atmosphere we can deduce the amount of aerosol and gases in the air.

Credit: NASA

Another operating mode, which will be used heavily during ARISE, would be the zenith (or upward) viewing mode. Here, we look upward to the sky and measure the diffused radiation that originated from the sun, but now is scattered due to aerosols and clouds. We use this measurement, along with assumptions on ground surface properties, cloud height, and the surrounding atmospheric composition to derive cloud properties such as optical depth (how much light gets through the cloud) and the size of water droplets in the cloud.

Credit: NASA

The last and most involved measurement mode we have is the Sky-Scanning mode. Here we measure the diffused sun radiation, that is light not coming directly from the sun, at different distinct angles from the sun (remember that we know where the sun is because we are tracking its location). This radiation is the result of scattered light from aerosols in the atmosphere. The amount of light at the different angles can tell us something about these aerosol particles, such as how well they absorb sunlight (and heat the earth), their shape (sphere or irregular), and their size.

Credit: NASA

This entry originally appeared on the NASA Earth Observatory blog Notes from the Field.

http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/blogs/fromthefield/2014/09/08/may-the-4star-be-with-you/

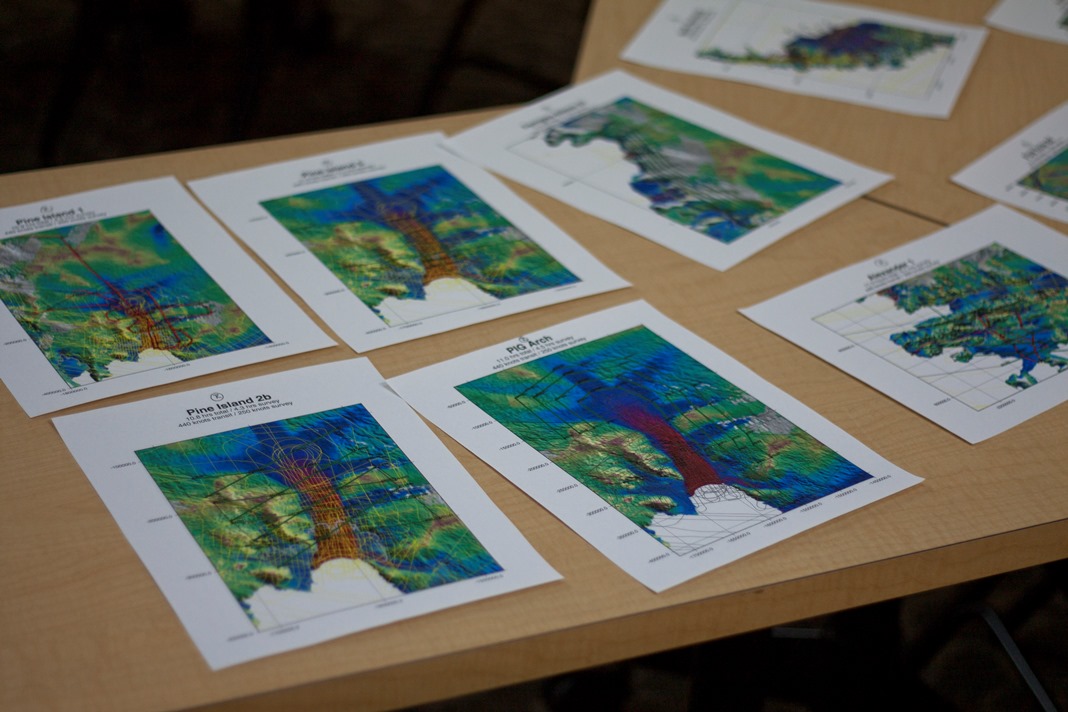

Above is an image mosaic from the Digital Mapping System aboard the NASA P-3 showing the terminus of the De Geer Glacier in east Greenland. The heavily crevassed end of the glacier is to the left of the image and large icebergs are to the right. Credit: NASA / DMS / Eric Fraim

Above is an image mosaic from the Digital Mapping System aboard the NASA P-3 showing the terminus of the De Geer Glacier in east Greenland. The heavily crevassed end of the glacier is to the left of the image and large icebergs are to the right. Credit: NASA / DMS / Eric Fraim