Welcome to the Operation Ice Bridge blog.

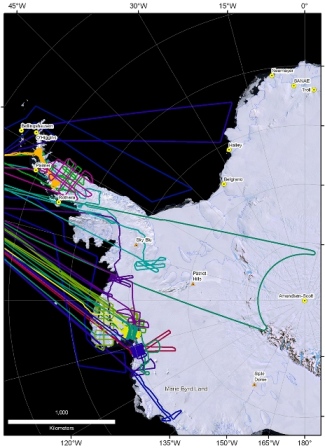

This new NASA mission is the largest airborne survey of polar ice ever flown. It is also the most sophisticated, using the latest scientific instruments to give an unprecedented three-dimensional view of the ice sheets, floating ice shelves, and sea ice of both the Arctic and Antarctic.

In this blog you’ll hear from a wide range of people involved in Ice Bridge as the mission begins its new expedition: flying over western Antarctica in NASA’s DC-8 starting in October. The base of operations is Punta Arenas, Chile, at the very southern end of South America.

– Steve Cole, NASA Office of Public Affairs, Washington, D.C.

From: Seelye Martin, Chief Scientist, Operation Ice Bridge

Seelye Martin, University of Washington, in Thule, Greenland this May. Mt. Dundas is in the background. Credit: Sinead Farell

I first got involved in polar studies in 1970, when I was hired as an assistant professor at the University of Washington in Seattle. At the university, I did a variety of cold room experiments on sea ice, then took part in a large number of sea ice studies in the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas using land-based helicopters.

Later, working from the NOAA ship Surveyor and Coast Guard icebreaker Westwind, I participated in several cruises studying the sea ice of the Bering Sea, serving as chief scientist on two of these cruises. I also worked in the field and laboratory on the mechanics of how spilled oil interacts with sea ice, and made use of satellite data to study the large-scale sea ice behavior. This research led to my coming to work at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., in 2006 as Cryospheric Program Manager and then to my current role as chief scientist of the Ice Bridge campaign.

One reason that I took the position at NASA and am continuing with the Ice Bridge work is my concern over the diminishing Arctic sea ice cover and the recent accelerating losses from the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets. The excitement for me in helping to plan and run this campaign is to participate in the design of experiments to replace the observations made by the aging NASA ICESat satellite, and to focus airborne observations on the rapidly changing regions of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets.

For the Antarctic flights, we have a comprehensive suite of instruments: lasers for the ice surface elevation, ice-penetrating radar for the bedrock topography, snow radar for snow thickness on sea ice, a gravimeter to measure the shape of seawater-filled cavity beneath the ice tongues, a digital mapping camera to measure three-dimensional relief, and a variety of precision navigation tools to determine where we are and to allow us to follow the ICESat tracks.

This instrument suite should lead to a unique set of ice sheet and sea ice observations. And by comparing the measured ice elevations with previous ICESat tracks, we’ll be able to determine the rates at which the critical glaciers are losing volume.

We have collected an enormous amount of data and are keen to analyze the data together with our colleagues when we are back in our labs. From the analysis of this data we will gain a much more detailed understanding of how the glaciers, ice sheets, and sea ice respond to changes in the climate system.

We have collected an enormous amount of data and are keen to analyze the data together with our colleagues when we are back in our labs. From the analysis of this data we will gain a much more detailed understanding of how the glaciers, ice sheets, and sea ice respond to changes in the climate system.