By George Hale, IceBridge Science Outreach Coordinator, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Success in science takes many things. Dedication and hard work are just a couple, but one thing that airborne science requires that other disciplines don’t need is aircraft. Without aircraft airborne science would just be science. And one thing is certain about aircraft. They require constant and vigilant maintenance to keep operating at their peak. NASA airborne missions like Operation IceBridge rely on skilled and dedicated mechanics and technicians to keep their planes flying in some of the harshest conditions around.

But finding people with the right balance of training and temperament to work on NASA’s fleet of aircraft is becoming more difficult. With a decreasing interest in working in the aviation field, an aging workforce and increasingly specialized training needed, NASA managers are finding it harder to hire the kind of people needed to keep things going.

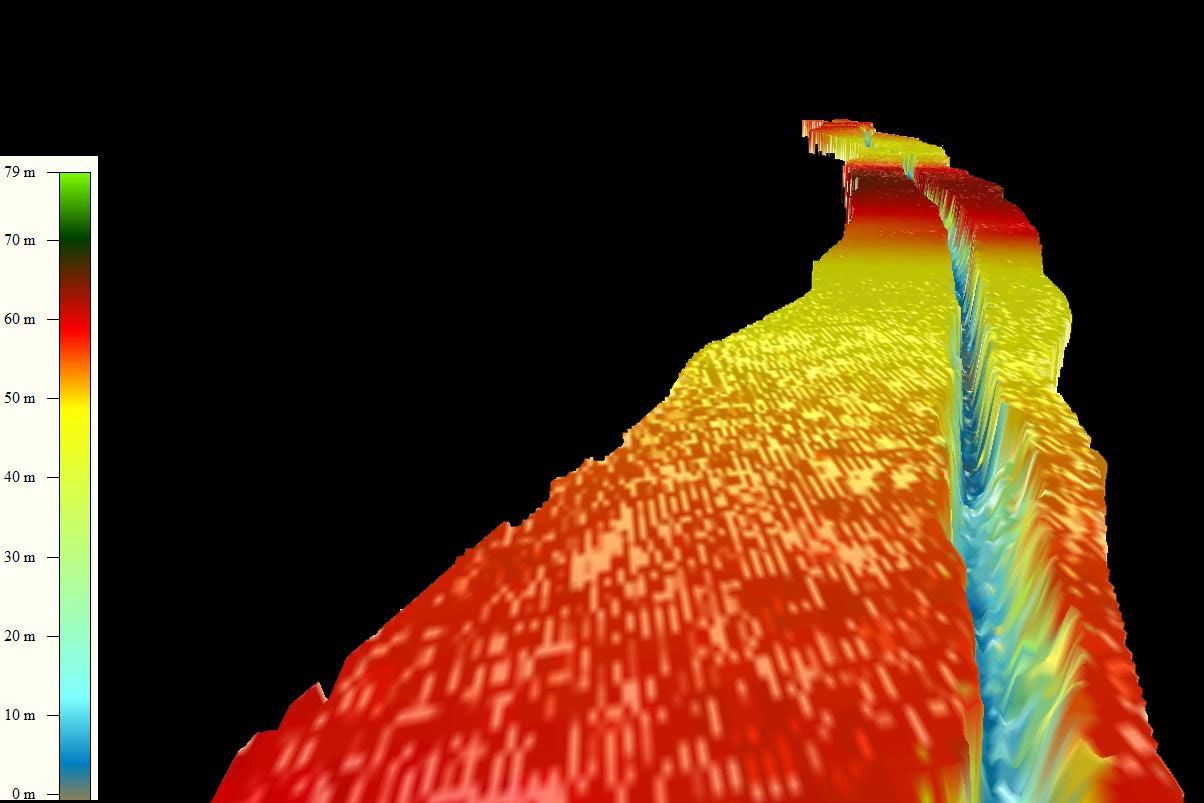

The IceBridge DC-8 undergoing final preparations for the first Antarctic campaign flight of 2012. Credit: NASA / Jeremy Harbeck

Top-notch Training

Being an aviation mechanic requires something called an aircraft and power plant, or A&P license, which gives its holders permission to work on any aircraft the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration controls, from ultralights to jumbo jets. The FAA only grants this license after applicants have completed rigorous training and passed three written, three oral and three hands-on tests. “Before you even get to put your hands on an airplane, there’s a lot of stuff you have to do,” said NASA DC-8 crew chief James C. Smith III.

Most people in the field got their training in one of two places. “You can either go to a two-year college or get what you need through military experience,” said Smith, who spent years in the U.S. Army working on helicopters. Today an increasing proportion come from the military as civilian training programs have been losing popularity. “Several college specific A&P schools have closed because they don’t have enough people coming through,” Smith said.

NASA’s Ikhana uninhabited aerial vehicle, one of the many aircraft that NASA’s technicians keep in top condition. Credit: NASA / James C. Smith III

NASA engineering technician Rich Souza came to NASA after several years both in the U.S. Air Force and private industry. Souza specializes in aircraft engines, working in the engine shop at NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center and keeps the DC-8 running at its peak. For him, the military was a great way to go and he recommends it to anyone who is interested in doing hands-on work with aircraft. “They give you the skillset, the aptitude and the attitude you need to do your job,” Souza said.

Brad Grantham, a NASA avionics technician, also speaks highly of military training, though he earned his position in a less conventional way. He started working with aircraft right after high school, taking a low-paying entry level job and working his way up the ladder. “Any time I found a position to advance and learn more about aircraft systems, I took it,” Grantham said. Avionics, Grantham’s specialty, covers everything electronic in the aircraft from navigation systems to the plane’s satellite communications system, all important when flying anywhere, let alone over Antarctica. “An aircraft can’t just pull over if there’s a problem,” Grantham said.

Avionics technician Brad Grantham (right) and Airborne Topographic Mapper team members Matt Linkswiler (left) and Robert Harpold prepare instruments for the IceBridge campaign. Credit: NASA / Tom Tschida

Never a Dull Moment

No matter how one learns about aviation, once at NASA, technicians enter a field where no two days are the same. Technicians are always reconfiguring aircraft for different missions and although they may have favorite aircraft, they work on more than just one. NASA’s fleet is diverse, ranging from the propeller-driven P-3B, to giant 747s, to the ER-2 high-altitude research aircraft and a variety of other planes.

This diversity of aircraft brings a refreshing variety to a busy job, but one of the big perks of working on NASA aircraft is that technicians go where the plane goes. Grantham and Souza have traveled many places around the world during their time with NASA and both have deployed to Punta Arenas, Chile, three times to support the DC-8 for Operation IceBridge.

In addition to their usual ground duties, working on aircraft mechanical and electrical systems, NASA technicians also pull a second duty as safety techs aboard the aircraft. This involves showing passengers how to use the aircraft’s safety equipment, keeping the aircraft clean and everything aboard secure and generally keeping everyone on board safe. Flying on scientific missions aboard planes they maintain is another thing that separates NASA’s technicians from aviation techs in other organizations. “It’s nice to see things from both sides,” said Grantham.

Group photo of IceBridge team in front of the NASA DC-8. Credit: NASA

The Path Taken

The road to becoming one of the people responsible for keeping NASA’s planes flying begins early on. Both Souza and Grantham realized at a young age that they wanted to work with aircraft in a personal and hands-on way. Preparing for such a career means getting as much experience as you can with anything mechanical and electrical. “It gives a good baseline for further training,” said Souza.

Experience and knowledge count but hard work and adaptability are just as important. You need to stay positive and be enthusiastic. “I worked hard jobs to get better jobs,” Grantham said. “When you do hard work you get to learn more.” Also, being able to adapt to changing situations is vital. “You n ever quite know where you might go next or what you’ll be working on,” Souza said. “So you need to keep on your toes.”

With many of the aviation industry and NASA’s experienced technicians retiring and an impending shortage of qualified people, a career in aviation with NASA is something that many recommend for those who want to travel, do hands-on work and always have something new to learn and do. “It’s a pretty cool job,” Souza said. “How many people get to fly over Antarctica?”