On April 6, the IceBridge blog received a comment from a first-grade class in response to a March 30 post,”Notes from the Shack.” The class asked a series of questions based on Colleen McIntosh’s words and photos from Thule, Greenland, where she is working as a data analyst and programmer in a GPS Shack during NASA’s IceBridge mission. Answers to the class’ questions, below, were compiled by McIntosh.

On April 6, the IceBridge blog received a comment from a first-grade class in response to a March 30 post,”Notes from the Shack.” The class asked a series of questions based on Colleen McIntosh’s words and photos from Thule, Greenland, where she is working as a data analyst and programmer in a GPS Shack during NASA’s IceBridge mission. Answers to the class’ questions, below, were compiled by McIntosh.

Students: How cold is it there?

IceBridge: During the time we have been up here the temperatures have ranged from -12 to 35 F. Typically, like just about everywhere, it is colder in the morning and night, and as the sun rises higher in the sky it warms up. However, on average for the last week or so, it has been around 11 F throughout the day.

Students: Does it ever snow?

IceBridge: Yes it does snow here. However, it is extremely cold and dry up here. When the air is very cold there is a lack of water vapor. Snow is of course made of water, so if it is too dry — even though it may be very cold — it is less likely to snow. And if it does snow it doesn’t snow a whole lot. But since it is so cold up here, when it does snow, it takes a very long time for the snow to melt. So there is snow up here that may be from snowfalls months ago, it just hasn’t melted yet!

DC-8 crew members Leo Salazar and Scott Silver in blowing snow on the ramp shortly before takeoff from Thule Air Base to the fifth science flight of Operation IceBridge. Credit: Michael Studinger

Students: How many people are working with you?

Students: Is it ever springtime there?

IceBridge: They do have all four seasons up here, however spring and fall are very very short compared to winter and summer. During the summer and winter there are about three months where they have either “24 daylight” or “24 nighttime.” And then for about a month before and after winter and summer, it is either quickly getting dark or quickly getting light. And then for around a month or so in fall and spring there is “normal sunlight time.”

Students: Is that mountain made of ice?

IceBridge: No, Dundas Mountain is made out of rock and dirt, just like mountains we have in the United States. It is just surrounded by and topped with a lot of snow and ice this time of year. You can climb the mountain when it is warm enough, but it is a very hard climb. Toward the top there is even a rope to help you pull yourself up the rest of the way up the mountain because it becomes very steep!

Students: How tall is that mountain?

IceBridge: The mountain is about 700 feet high

Sled dog race in Thule, Greenland, with Dundas Mountian in the background. Credit: Michael Studinger

IceBridge: It is about 1.5 miles to Dundas Mountain from the GPS shack.

Students: Why does the sun look so big and so close to the Earth?

IceBridge: When celestial objects, like the sun and the moon, they get closer to the horizon and they “appear” bigger. However, this is just an optical illusion. The fact is that the illusion is dependent entirely on the visual cues provided by the terrain when the moon is near the horizon, and the lack of such cues when it’s at the zenith (directly above our heads). To prove this, try viewing the moon through a cardboard tube or a hole punched in a sheet of paper to mask out the landscape — the illusion disappears.

This time of year time of year the sun stays in the sky for almost 24 hours. Come April 17, the sun will not set here for the next three months. This is because of the way the Earth is tilted. Right now the Earth is tilting toward the sun, and because Greenland is just about at the top of the world, the Earth’s top always sees the sun. But something to note is that although the sun does not set for three months, the temperature still only reaches 60 degrees at its hottest!

Students: How do you make electricity?

IceBridge: There are several diesel generators that power the entire base. Also on the base are several cylindrical containers that hold the fuel for the airplanes that land and take off from this base. There used to be a lot more containers, but now that the base isn’t used as much as it was in the 1950s and 1960s, they have taken out these containers.

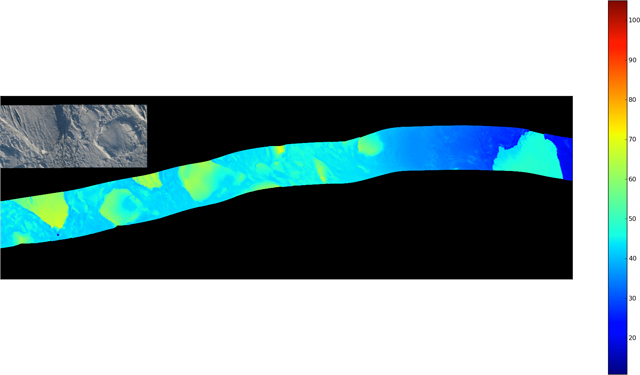

Staying on the ground as part of the GPS base station crew, there isn’t a whole lot to do as far as maintaining the receivers. The Land, Vegetation, and Ice Sensor (LVIS) team has three receivers, all different. We have a Javad which records data at 20 hertz, a Novatel which records data at 10 hertz and an Ashtech which records data at 2 hertz. These receivers are running all day every day.

Staying on the ground as part of the GPS base station crew, there isn’t a whole lot to do as far as maintaining the receivers. The Land, Vegetation, and Ice Sensor (LVIS) team has three receivers, all different. We have a Javad which records data at 20 hertz, a Novatel which records data at 10 hertz and an Ashtech which records data at 2 hertz. These receivers are running all day every day.