The Dryden-based DC-8 flight crew handles the plane on its first Antarctica 2011 flight. Credit: Michael Studinger/NASA

By Michael Studinger, IceBridge Project Scientist, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Punta Arenas, Chile – Today marks a milestone for IceBridge. For the first time, both NSF’s Gulfstream V (G-V) and NASA’s DC-8 aircraft took off from Punta Arenas for science flights over Antarctica.

The G-V, with NASA’s Land Vegetation and Ice Sensor (LVIS) on board, headed toward Evans Ice Stream, which flows into the southern part of the Ronne Ice Shelf in Antarctica.

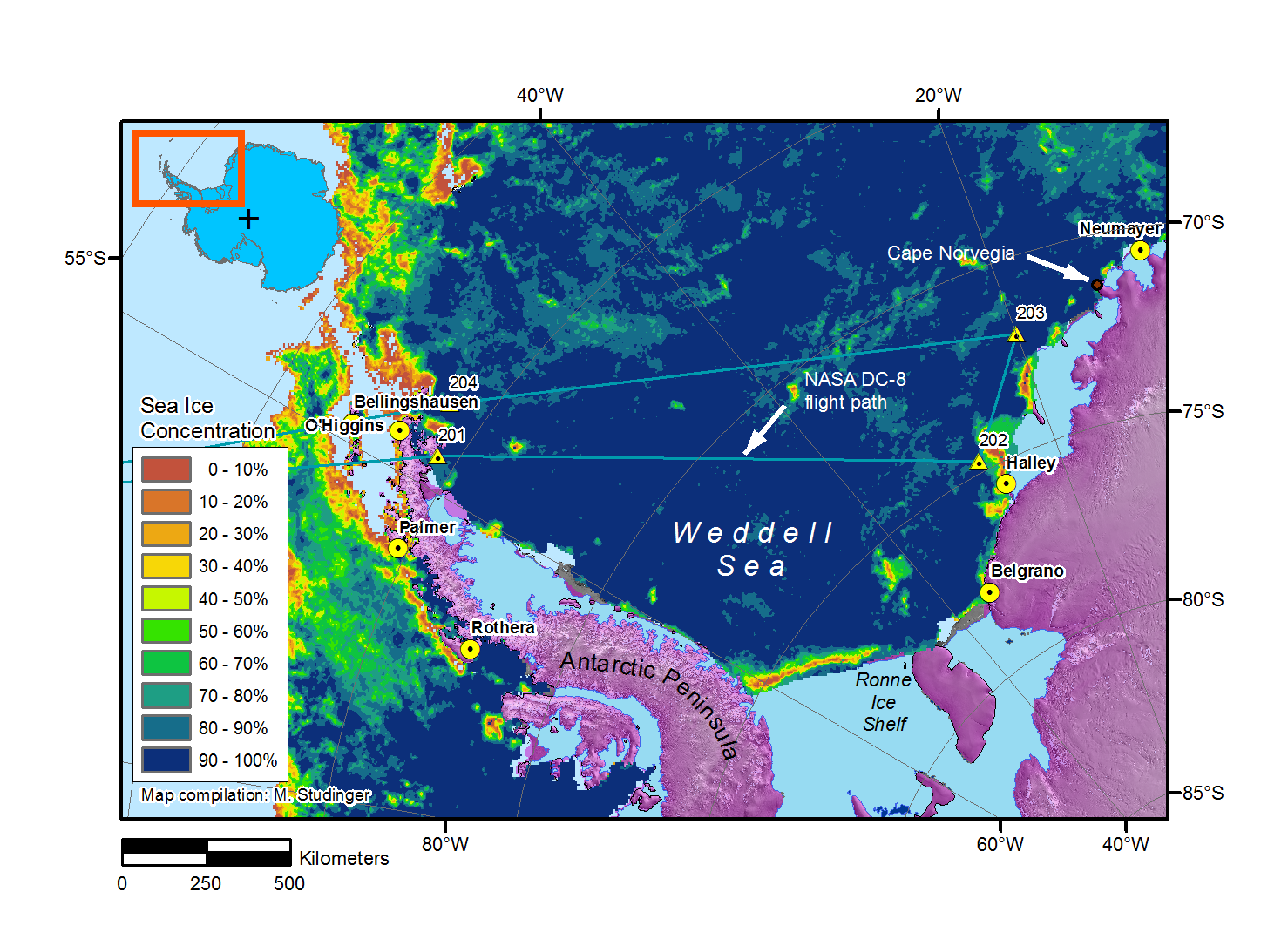

The DC-8, with its suite of IceBridge instruments, headed toward the Weddell Sea to measure the thickness of the sea ice and the snow on top of it along two 1,700-km-long transects that cross the entire Weddell Sea from east to west. It’s like flying from Chicago to Miami and back at 1,500 feet above the ground. This mission is an exact repeat of two missions that we have flown in 2009 and 2010. The goal is to measure how much sea ice is being exported through the “gate” connecting the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula with Cape Norvegia and determine the changes that occur over time. The export of sea ice from this area is a major contributor to the total ice volume exported into the Antarctic Circumpolar Current.

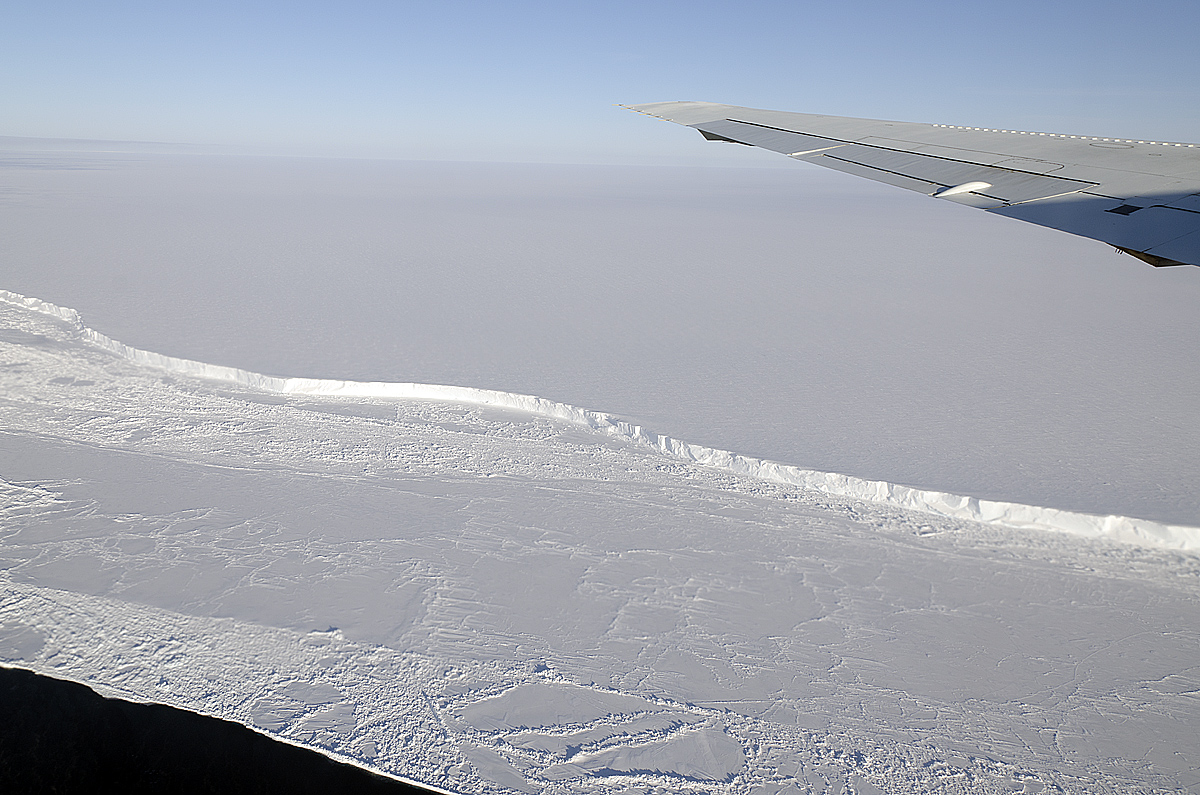

The DC-8 takes in a stunning view of the Brunt Ice Shelf on its first Antarctica 2011 flight. Credit: Michael Studinger/NASA

The Weddell Sea encompasses a large area and the chances of getting such a large area cloud-free are small. We rely on several different weather forecast models, satellite imagery and meteorologists at the Punta Arenas airport to get a picture of the weather conditions in the survey area before the flight. It requires many years of experience to interpret the different pieces of information and make a decision in the morning whether we launch a mission into the Weddell Sea or not. There is not a single weather station in the Weddell Sea or nearby to provide observations we could use to confirm the model predictions. Imagine needing to rely on a weather forecast back at home that has no weather data between Chicago and Miami. During the flight we encountered the expected mix of clouds, fog and sunshine. We often were able to fly below the clouds and continue to collect data. All in all a great start to our Antarctic campaign.