From: John Sonntag, OIB Management Team member and ATM Senior Scientist, Wallops Flight Facility

One simple and irrefutable fact of airborne science is that things will go wrong. We utilize complex machines, such as airplanes and unique science equipment, in remote and often austere places, far from help and spare parts. We are heavily dependent on weather forecasts, in parts of the world with relatively little real data to inform the forecast models. These issues inevitably create challenges and problems. Sometimes the bad stuff is minor, sometimes it is crippling, and sometimes it just plain gets to you. For me, the Operation IceBridge Antarctic 2010 deployment had the third effect.

One simple and irrefutable fact of airborne science is that things will go wrong. We utilize complex machines, such as airplanes and unique science equipment, in remote and often austere places, far from help and spare parts. We are heavily dependent on weather forecasts, in parts of the world with relatively little real data to inform the forecast models. These issues inevitably create challenges and problems. Sometimes the bad stuff is minor, sometimes it is crippling, and sometimes it just plain gets to you. For me, the Operation IceBridge Antarctic 2010 deployment had the third effect.

Of the four NASA-operated OIB field programs executed to date (remember that OIB funds two smaller university-operated efforts as well), this one has been the most beset with problems. First, our calibration mission prior to departing was delayed by the discovery of a problem with the DC-8’s rudder trim tab, which had to be replaced. This was no big deal, really, and obviously could not be a harbinger of things to come.

Shortly after we arrived in Punta Arenas last month, several members of our team got a bad stomach bug, or possibly food poisoning. Everyone recovered fully within a few days, but from what I was told it was the sort of stomach problem that makes sudden violent death seem like an attractive option. During and shortly after the gastrointestinal crisis, members of two different instrument teams were involved in (separate) automobile accidents, incredibly enough, at the same intersection. Thankfully everybody was OK, though issues with insurance, local police, and rental car agencies persisted for weeks.

Around the time of the second auto accident, it was also becoming clear that weather had become a major impediment to our operations. We watched a seemingly endless train of weather systems relentlessly pound our primary science targets around Pine Island Bay and the Peninsula, utterly frustrating our hopes to get in there for several weeks. We were able to hit other high-priority science targets, including three important sea ice surveys and a pair of flights around the South Pole, but soon we began to run out of targets other than the areas that were consistently socked in.

Next, that became a moot point when our mechanics discovered a broken fitting in a landing gear door on the DC-8. It took a few days to get the replacement part all the way down to Punta Arenas, and once it got here and the repair was made, well, the weather hadn’t really improved. So we took a chance on a marginal weather Saturday to get more than half of our “Peninsula 23” flight done. That raised spirits considerably, until the next morning when mechanics discovered a failed fuel flow sensor in the #3 engine. Luckily, we had a spare. Unluckily, the spare was also broken. It would take a few days to get another part shipped here.

I hit my personal rock-bottom three days after that, when word came around that there had been a foul-up in the shipping of the replacement fuel-flow sensor and that it was still sitting in a cargo warehouse at LAX. I went for a walk on the beach, looked out at the Strait of Magellan, and found myself idly wondering what people walking nearby might think if they saw a grown man cry, or perhaps throw a tantrum. I also ran across Science Team Lead Seelye Martin, who was out on the beach for the same reason. We exchanged approximately five dejected-sounding words and parted when neither of us could even work up a smile to help buck the other up.

In my 17+ years as an airborne scientist I’ve seen illnesses, scary traffic accidents, and especially, bad weather and broken airplanes adversely affect plenty of field programs. I just can’t recall so many diverse problems afflicting a single deployment as we have seen in this one. And I’ll admit it – the stress and frustration got to me. And I’m pretty sure I wasn’t alone, after seeing lots of long faces in project meetings and around the breakfast room at the hotel. Something else that makes this difficult to take is the inevitable comparison to our remarkable success here in 2009, when we racked up an incredible 21 long-distance science flights. We all went home after that feeling like conquering heroes, even though we knew we’d been lucky with favorable weather and a smoothly-running airplane.

But then, things began to look up. First, word came down that the long-delayed part was on a plane, on its way south out of LAX. We’d have it Thursday evening and could fly Friday. Then, our meteorological analysis showed unmistakable signs that the weather pattern that had bedeviled us for weeks was changing! Pine Island Bay and its surroundings were finally opening up! This was just in time for the part to arrive, and for us to knock out 2-3 flights in quick succession to finish up before we’re due to pack up and be home in time for Thanksgiving.

As it turns out, the fun wasn’t quite over yet. The weather forecasts held up beautifully, but another minor foul-up with customs paperwork delayed the part until the flight due to arrive at 3 am Friday morning. Worse, when it got here it immediately got locked up in another cargo warehouse which refused to open until 9 am Friday, despite the fervent nocturnal pleadings of our maintenance guys waiting nearby. With a few hours needed to make the repair, we decided to delay our takeoff to 3 pm, making for a very long day for everybody but meaning that we’d maximize our chances for a 3-flight run to finish up the project. During the morning while our crew was making the (rather involved) repair out on the open ramp, the nastiest local weather we’ve seen since our arrival blew through, with howling 30-40 knot winds, rain and blowing snow, making their time-pressured work even more difficult and uncomfortable, and making the rest of us fret about cross-winds, snow accumulation on the plane and all the other problems such a squall can create. But by the time they finished the repair, the sun was back out and we were go to launch! We flew a 100% successful evening mission in perfect weather conditions over the Thwaites and Pine Island Glacier basins yesterday, after the nail-biting drama of the overnight and morning, and landed around 2 am.

That was yesterday. As I write this account, it is now Saturday and we are again over Pine Island Glacier enjoying ideal weather. Most of us only had time to sleep 4-5 hours after the late-night landing yesterday and today’s noon takeoff, and there are lots of hollow eyes as well as a styrofoam menagerie of coffee cups strewn about the cabin. Nevertheless this is now a happy and fiercely determined team. We are now engaged in a full-bore, all-out sprint to the finish line, which we define as our departure to the north, and eventually home, around mid-day Monday. Today is flight #10 and we have now hit all of our high-priority science targets at least once.

We also have a fighting chance at one last science flight during the day tomorrow, Sunday. To do that requires one last spasm of exertion from the entire team – flight crew, maintenance crew, instrument engineers, scientists and support folks, in order to get the flight done early enough to get back to Punta, pack the plane and load up in time to make it north to Santiago on Monday, Palmdale on Tuesday, and to our respective homes hopefully by Wednesday night. Everybody here is fired up to do it, but par for the course, there is a problem. The workers who pump fuel into airplanes at the Punta Arenas airport, including ours, are threatening a labor action – a strike.

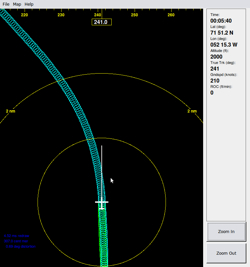

SOXMap is really just a “moving map” system, at heart not unlike the ones in consumer GPS units used in cars or for hiking, but simpler and highly specialized for remote sensing applications. SOXMap displays the aircraft’s current position and orientation relative to a science target, such as the sinuous centerline of a glacier (see the SOXMap illustration, left). It also displays the measurement swath being collected by a science instrument such as the ATM, drawn to scale. This display is piped to the pilots up front, using little tablet computers with very sharp, bright displays, which are mounted right on the control yoke. Our pilots use this information, which is continuously updated, to steer the aircraft and its sensor swath right where we want it. Some of our OIB pilots refer to SOXMap as “the Pac Man display”, in reference to the old video game where the player guides a little mouth around a screen chewing up dots. The beauty of SOXMap is its versatility. Our bread-and-butter use for it with OIB is to follow sinuous glacier centerlines with any degree of curvature, but SOXMap is also useful for area-mapping applications, or really any targeted flying.

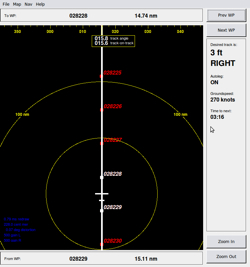

SOXMap is really just a “moving map” system, at heart not unlike the ones in consumer GPS units used in cars or for hiking, but simpler and highly specialized for remote sensing applications. SOXMap displays the aircraft’s current position and orientation relative to a science target, such as the sinuous centerline of a glacier (see the SOXMap illustration, left). It also displays the measurement swath being collected by a science instrument such as the ATM, drawn to scale. This display is piped to the pilots up front, using little tablet computers with very sharp, bright displays, which are mounted right on the control yoke. Our pilots use this information, which is continuously updated, to steer the aircraft and its sensor swath right where we want it. Some of our OIB pilots refer to SOXMap as “the Pac Man display”, in reference to the old video game where the player guides a little mouth around a screen chewing up dots. The beauty of SOXMap is its versatility. Our bread-and-butter use for it with OIB is to follow sinuous glacier centerlines with any degree of curvature, but SOXMap is also useful for area-mapping applications, or really any targeted flying. Even cooler than SOXMap is its sibling, “SOXCDI”. SOXCDI (image right) incorporates a moving map display similar to the one in SOXMap, but unlike SOXMap, SOXCDI can actually steer the airplane automatically! It is designed for cases where we fly long straight lines, such as grid lines or satellite ground tracks. We can do the same thing successfully using only SOXMap, but for long straight lines this demands lengthy periods of concentration from our pilots and can be extremely tedious for them. So SOXCDI continuously compares the current position of the aircraft to a desired straight-line track connecting a pair of waypoints (for any navigation geeks who might be reading along, the straight line is actually a great circle, and I plan to add a selectable rhumb line option as well). Doing a little math with that comparison, we always know how far we are from the desired track and whether we are right or left of it.

Even cooler than SOXMap is its sibling, “SOXCDI”. SOXCDI (image right) incorporates a moving map display similar to the one in SOXMap, but unlike SOXMap, SOXCDI can actually steer the airplane automatically! It is designed for cases where we fly long straight lines, such as grid lines or satellite ground tracks. We can do the same thing successfully using only SOXMap, but for long straight lines this demands lengthy periods of concentration from our pilots and can be extremely tedious for them. So SOXCDI continuously compares the current position of the aircraft to a desired straight-line track connecting a pair of waypoints (for any navigation geeks who might be reading along, the straight line is actually a great circle, and I plan to add a selectable rhumb line option as well). Doing a little math with that comparison, we always know how far we are from the desired track and whether we are right or left of it.

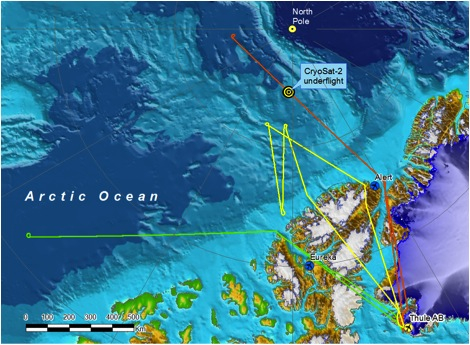

We had a very successful campaign and accomplished many things although it was challenging at times. Worse than normal weather over the Antarctic Peninsula and Marie Byrd Land and aircraft downtimes slowed down our progress during the deployment. By adapting our plans to the situation we were able to fly 10 successful missions making use of 84% of the allocated science flight hours. The IceBridge teams have spent 115 hours in the air collecting data and have flown 40,098 nautical miles, almost twice around the Earth. We collected landmark sea ice data sets in the Weddell, Bellingshausen and Amundsen Seas. We have now flown over every ICESat orbit ever flown by completing an arc at 86°S, the inflection point of all ICESat orbits around the South Pole. We have surveyed many glaciers along the Antarctic Peninsula, the Pine Island Glacier area and in Marie Byrd Land. We have collected data along a sea ice transit at the same time ESA’s CryoSat-2 satellite flew overhead allowing us to calibrate and validate the satellite measurements.

We had a very successful campaign and accomplished many things although it was challenging at times. Worse than normal weather over the Antarctic Peninsula and Marie Byrd Land and aircraft downtimes slowed down our progress during the deployment. By adapting our plans to the situation we were able to fly 10 successful missions making use of 84% of the allocated science flight hours. The IceBridge teams have spent 115 hours in the air collecting data and have flown 40,098 nautical miles, almost twice around the Earth. We collected landmark sea ice data sets in the Weddell, Bellingshausen and Amundsen Seas. We have now flown over every ICESat orbit ever flown by completing an arc at 86°S, the inflection point of all ICESat orbits around the South Pole. We have surveyed many glaciers along the Antarctic Peninsula, the Pine Island Glacier area and in Marie Byrd Land. We have collected data along a sea ice transit at the same time ESA’s CryoSat-2 satellite flew overhead allowing us to calibrate and validate the satellite measurements. One simple and irrefutable fact of airborne science is that things will go wrong. We utilize complex machines, such as airplanes and unique science equipment, in remote and often austere places, far from help and spare parts. We are heavily dependent on weather forecasts, in parts of the world with relatively little real data to inform the forecast models. These issues inevitably create challenges and problems. Sometimes the bad stuff is minor, sometimes it is crippling, and sometimes it just plain gets to you. For me, the Operation IceBridge Antarctic 2010 deployment had the third effect.

One simple and irrefutable fact of airborne science is that things will go wrong. We utilize complex machines, such as airplanes and unique science equipment, in remote and often austere places, far from help and spare parts. We are heavily dependent on weather forecasts, in parts of the world with relatively little real data to inform the forecast models. These issues inevitably create challenges and problems. Sometimes the bad stuff is minor, sometimes it is crippling, and sometimes it just plain gets to you. For me, the Operation IceBridge Antarctic 2010 deployment had the third effect.